HOPE not hate uses cookies to collect information and give you a more personalised experience on our site. You can find more information in our privacy policy. To agree to this, please click accept.

“There is a women who’s had surgery, she needs to be warm but there is nothing to heat the place […]. She was pregnant but…

“There is a women who’s had surgery, she needs to be warm but there is nothing to heat the place […]. She was pregnant but she was so tired and too cold… she lost her baby.”

Yazidi man in informal settlement Zakho

The lady was lying on the dusty concrete floor on the first level of an unfinished building, protected from the rapidly cooling winter winds by a tied blue tarpaulin. She was one of 70 people living across two floors and sharing just one toilet in this informal settlement in Zakho in northern Iraq, just a few kilometres from the Turkish border.

This was just one of numerous similar situations in the Zakho district, almost all inhabited by Yazidis from Sinjar who were fleeing the advance of the Islamic State (IS). It is hard to believe but these people, along with the many thousands more in the formal camps, are the lucky ones.

They are the survivors.

The barbarism of the IS and the unimaginable experiences of its victims have shocked, saddened and infuriated the world in equal measure. However, those caught, mutilated and murdered remain the minority. What of the lives of those who survived, who fled and escaped IS’s terror?

They are the living victims.

The rise of IS has dramatically escalated the number of refugees fleeing Syria, while in Iraq the expansion of IS has affected over 5.2 million people with nearly two million being displaced between December 2013 and November 2014.

However, with the recent history of instability and war in Iraq, this mass of refugees is flocking to the camps of already-internally displaced people (IDPs), some of whom left their homes as long ago as 2004. The picture in Syria is perhaps even more complicated with some nine million Syrians having been displaced since the outbreak of civil war in 2011. Three million of these have crossed the borders into Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq, while 6.5 million are internally displaced inside Syria.

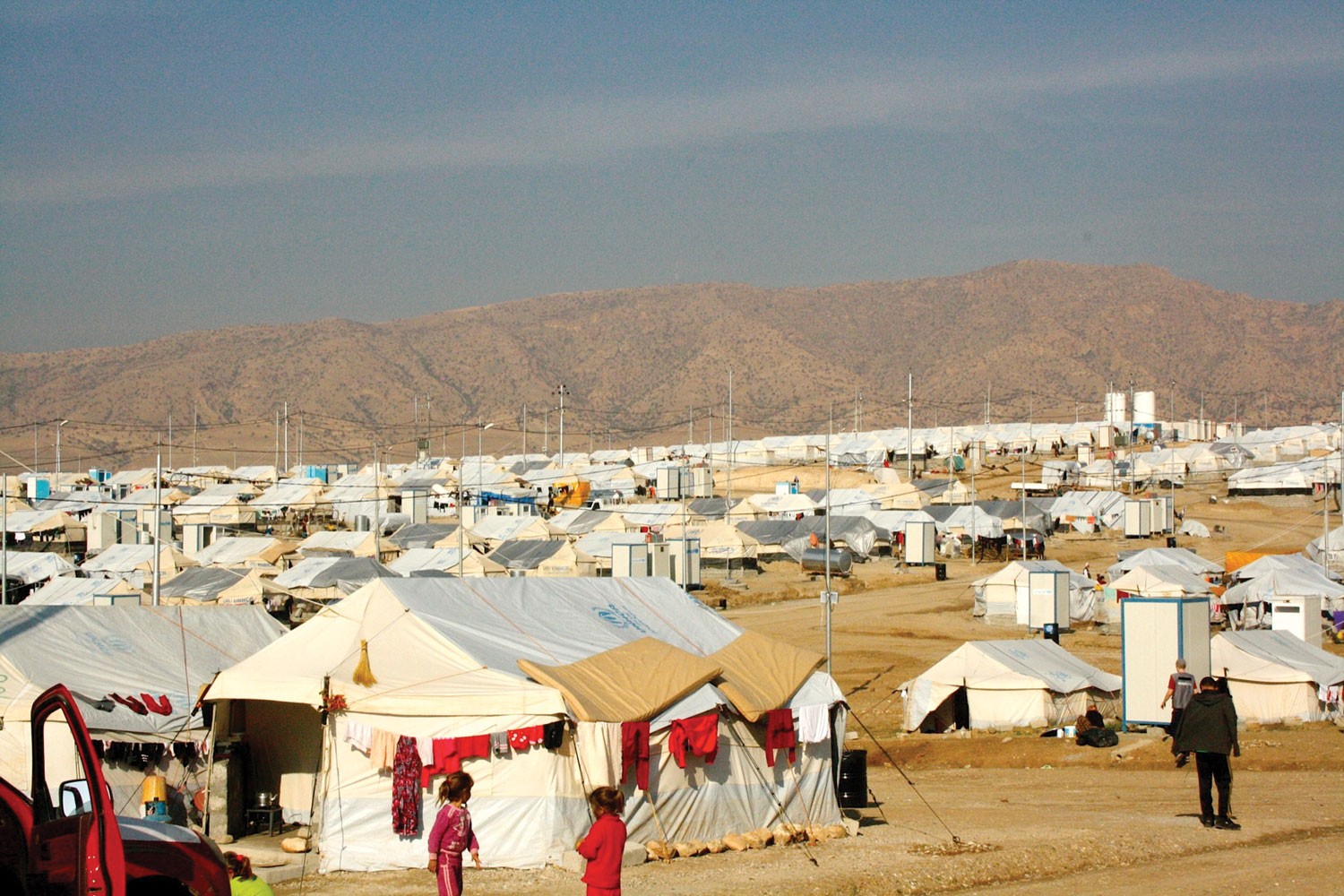

What is life like in the camps for the millions who have been forced to leave their homes and possessions and seek refuge in the tented cities that have sprung up across northern Iraq? There are millions of displaced people, all with different backgrounds, different circumstances and situations and importantly they are spread across different camps and informal settlements. All have their own story, as does each camp.

That said, there are commonalities that stand out. As with any area of settlement numbering thousands, there is good and bad to be found and, unsurprisingly with so many desperate people, there is crime and prostitution. But the camps are not just holding pens for victims, they are communities where people live. The men, women and children who have taken refuge under the tarpaulins and tents are not just hiding: they are living.

Kawergosk Camp, perilously positioned just down the road from IS-occupied Mosul, is home to around 10,000 Syrian refugees. As you drive over a hill, an expanse of white tents unfolds before you, more a town than a camp. Orderly rows of these tents, emblazoned with the United Nations logo, bring to mind every refugee camp you have ever seen on television. Yet, as you drive through the gates, park and walk into the camp itself, a different reality begins to emerge.

Turning the corner you find yourself on what can only be described as a shopping or high street. Little shacks line both sides of the road, bustling with everything from money exchanges that will change dollars, Iraqi Dinars and even Euros, to restaurants, barber shops and video game stores. Shoppers peruse the available wares while school kids head off to class, bags in hand.

“The ISIS emir answered me in a harsh tone: “Why? Do you have your house here? Do you have your village here? This is not your village and you have no house. I don’t want to see you talk about a house here. You don’t belong here. By tomorrow not one of you will remain here or come back here”.”

Kurdish interviewee forced from his home in northern Aleppo, Interview in United Nations Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic: Rule of Terror: Living under ISIS in Syria, (14 November 2014)

It is not uncommon to find televisions with satellite dishes, cookers and fridges inside the tents. The ingenuity and invention is remarkable, with the tents often being extended with second and sometimes even third rooms built of wood, concrete and bricks. In a matter of months, these people have managed to turn mere tents into new homes.

Life, of course, is very far from perfect. If you are willing to listen, there are plenty of people willing to tell you exactly why. Complaints range from a lack of privacy (parents unable to ‘hug’ while sharing a space with their children), through to missing favourite TV shows because ‘the reception is rubbish’. However, mundane problems like these, while plentiful, are just the tip of the iceberg.

While these often-ingeniously extended homes undoubtedly make the lives of the refugees better, people are going nowhere fast. The average life of a refugee camp is 17 years and while many will leave, find work, rent houses and move on, many will not. Often, they have lost everything except some savings that will not last forever and the concrete bases that waterproof their tents must simultaneously act as a constant reminder that they will not be going home any time soon, perhaps ever.

As winter draws in and the first snow appears in the air, new challenges arise. Fleeing in the dry Middle Eastern summer, most left with just the clothes on their back, meaning that today around 60% of these displaced peoples have no winter coats and 90% have less than one coat per person in a family.

Since the IS occupied several oil refineries, there have been oil shortages in the camps, leading to problems with cooking and keeping warm. Tragically, some have turned to watering down the kerosene, an act that, in turn, has led to stoves exploding.

Jallal, a Yazidi IDP from Sinjar now living in Khanke Camp, explained: “Life in this camp is good but we are afraid of one thing …. burning. The tents are too near to each other. Five tents have set ablaze and up until now three children and one women have died.”

Similar fires have occurred at other camps including Harsham, a small settlement just outside Erbil, the largest city and capital of Iraqi Kurdistan. A makeshift fruit and veg stand plays host to a group of 10 understandably angry men, all explaining how a recent fire burned down a tent in around 14 seconds. This time the women inside escaped.

Talking to this group of gesticulating figures, it became clear that IS’s expansion has affected the lives of millions of people in ways that are not immediately obvious. Apart from the capture of refineries, sometimes hundreds of miles away, IS’s control of arable land has pushed up prices and reduced rations in neighbouring areas. Even though the refugees have escaped, the IS still has the power to make their lives worse.

The coming winter poses major problems for all camps and while most are of a remarkably high quality – camps such as Kawergosk, Bagid Kandela and Chamishku – a rare few fall well below these standards.

As you turn off the main road onto a dirt track and head to within spitting distance of where Iraq, Syria and Turkey all meet, you encounter a small forgotten camp called Deirabon. Here, perched on the edge of a hill with a vista that plunges down to Syria one way and Turkey the other, lives a community of 1,200 Yazidis who fled from Sinja.

The camp, made up of large communal tents, was not managed but rather had sprung up spontaneously, occupied and seemingly abandoned to fend for itself bar the odd delivery of water. The toilets were unhygienic open pits within smelling distance of the tents. The tents themselves had no floor, thin and threadbare mattresses lying on open gravel and mud. Camp residents had received just one food delivery in the past three months, meaning they had had to scrape together what money they could to buy provisions from the local town. The diarrhoea that afflicted the camp in the summer had given way to hypothermia as increasingly bitter winter winds whipped across the top of the hill into the exposed huddle of tents. This was a world away from the buzzing town-like camps of Kawergosk or Bagid Kandela with their televisions and fridges.

If you look at the fallout of the much-publicised battle for Kobane in northern Syria, you can understand not only the scale but also nature of the arduous journey that refugees have been forced to make as a result of the IS’s attacks.

The month following 16 September saw between 170,000 and 200,000 people cross the border into Suruc, Turkey. Many then organised their own travel along the border between Turkey and Syria, until they reached the town of Silopi which sits between Iraq, Turkey and Syria. The journey took up to 10 days. Some then spent another 10 days in the border town waiting to be allowed across the border into Zakho in northern Iraq. For some, this has been the end of their journey but others they were then moved again, this time by the Kurdish authorities, to camps such as Gawilan Camp further south.

Of course, northern Iraq has not only had to deal with the thousands of people fleeing Syria but an ever-increasing number of internally displaced people resulting from IS’s eastwards expansion. Their ethno-religious background often heavily influences the final destination of those in flight.

The displacement of the Shabak and Turkmen Shia, for insstance, happened in two stages. Between early June and early August 2014, communities from Tal Afar fled towards Zummar and Sinjar, which were protected by Kurdish forces, while communities in Namrud and Mosul escaped towards the Nineveh Plain. However, when IS then expanded this triggered a wave of secondary displacement, sending IDPs towards the Kurdish region of northern Iraq or all the way to Shia governorates enclaves in South Central Iraq, a journey made by car or plane.

This process of secondary displacement also affected the Christian minorities in the Nineveh Plain. In June and July, around 50,000 Christians fled Mosul for a number of towns in the plains but, when IS expanded again in early August, they had to move again, this time joined by a further 150,000 Christians from the Hamdinya, Tilkaif and Shihan districts.

Therefore, contrary to what one might assume, people do not just flee to the nearest safe haven but rather head towards predestined locations influenced by the perception of the welcome they will receive. As such, Christians have fled to other Christian areas, Yazidis to Yazidi areas, Shia to Shia areas, etc.

One of the underreported aspects of this movement of people is the negative demographic impact it has and can cause in this part of the Middle East. While it would be absurd to suggest Iraq was previously some sort of multicultural utopia – many were persecuted by Saddam Hussein’s Ba’athist regime – it had towns and cities with minority communities including Yazidis, Shia Muslims, Assyrian, Syriac, Chaldean and Armenian Christians, Druze, Mandeans and Shabaks, some of which have lived in the region for over a thousand years. The ruthless expansion of IS has forced many of these groups to flee, turning once mixed areas into homogeneously Sunni regions. The understandable desire of minority groups to seek refuge within similar communities has meant that a once ethnically-mixed province has stratified along ethno-religious lines.

Some have left the region altogether, with Christians often fleeing to Europe while many Christian refugees in northern Iraq have already stated they have no intention of going home even if IS is defeated. Other minority groups feel the same. Despite often having ancient roots in the towns and cities they formerly inhabited, trust has broken down completely; these displaced minorities have witnessed their former neighbours turn on them and do not to intend to return and live among them, even if this one day becomes possible. Lines are being redrawn, not just on the map but among the peoples of the Middle East too.

The Rise of the Islamic State (IS)

The rise of the Islamic State from non-existence to a fully existing state has happened with remarkable and alarming speed. Understandably many have been reticent to use the name “Islamic State” (IS), fearing that its adoption legitimises the group’s claims to have resurrected the historical Islamic Caliphate. Even Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott has argued that “To use this term [Islamic State] is to dignify a death cult”. But for all intents and purposes, it is a functioning (albeit terrorist) statelet. Estimates vary widely but the IS is somewhere between the size of Belgium and Great Britain, occupying swathes of land in Syria and Iraq and, more recently, small areas of Libya such as the town of Derna (100,000 people) and parts of Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. In total, it now has military allies in 11 countries and support in 61 regions via 31 groups. Its armed forces are estimated at anywhere between 30,000 and 200,000 militants while its value in cash and assets is an estimated $2,000,000,000, with an income of $3,000,000 a day from oil and gas exports alone. Internally, the state has a legal system based on a super-strict interpretation of Islamic law (Sharia), which is supported by a religious police force – the Hisbah – which mercilessly enforces compliance and distributes posters around occupied cities, showing citizens “how” to pray and prescribing how women should dress. The group emerged as just one of hundreds of militant groups in Syria, which has served as something of a primordial swamp for armed factions in the last few years. However, its earliest origins date back to 2004 with the creation of Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) by Abu Musab Al- Zarqawi, the ‘Emir of Al Qaeda in the Country of Two Rivers’. Following mergers with other like-minded militants in 2006, AQI rebranded itself as the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI) and, in 2011, then led by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, joined forces such as the Al-Qaeda affiliate Jabhat Al-Nusra in the fight against government forces in Syria. The union was fleeting however, with a hostile split emerging in April 2013 – ISIL (Islamic State in Iraq and Levant) as it became known, was more concerned with the consolidation of power and the creation of a state than fighting the Syrian government – and ISIL subsumed much of Al-Nusra’s capabilities, with armed confrontations between the two in 2014. By February 2014, after many months of arguments Al-Qaeda finally cut all ties with ISIL citing its “notorious intransigence”. Despite this, 2014 has been a year of remarkable expansion for the group. Between late December 2013 and the end of May 2014, it made gains in the Anbar province in western Iraq with bloody fighting in Fallujah and Ramadi. In June and July, it took control of Iraq’s second city of Mosul and spread across Nineveh and the central governorates of Salah Al Din, Diyala and Kirkuk. It was during these sizeable advances that it once again changed its name, this time from ISIL to Islamic State. In August, it captured the towns of Sinjar, Zumar, and Wana in northern Iraq. Then in October, the near-collapse of the Iraqi army saw IS advance on Baghdad, taking it to within just 25km of the city’s airport. In addition to all of these remarkable land grabs has been the accumulation of other small pockets of territory, such as the town of Derna in Libya. |