HOPE not hate uses cookies to collect information and give you a more personalised experience on our site. You can find more information in our privacy policy. To agree to this, please click accept.

Download the full report or read key takeaways below.

State of HATE 2022 – the leading annual report outlining the key trends and changes in the domestic and international far right – shows how the past year has led to an environment in which we will likely see the return of far right activists back on the streets, standing in elections and exploiting the uncertainties created by economic hardship.

After years in the political wilderness, the crises we’ve collectively faced over the past two years have emboldened cynical far right activists to exploit our fears and uncertainties and return to traditional methods of campaigning.

The report predicts that the growing unease in society could be exploited by far right extremists. Polling shows that 80% of people now have less disposable income than they did a year ago, and 68% now believe that Britain is ‘going in the wrong direction’.

State of HATE 2022 outlines ways in which the far right threat is now pervading all aspects of our society, but also the steps we can take to stop blatant far right rhetoric and conspiracy theories becoming part of normal discourse and prevent fascists and extremists from dividing our society.

Download the full report or read selected chapters below.

One of the newest militant anti-vaccine groups has already been infiltrated by the far right, says DAVID LAWRENCE.

As an insurgent mindset has spread into sections of the UK’s conspiracy theory-driven protest movement, we have witnessed the emergence of militant anti-vaccine networks that eschew street demonstrations in favour of radical direct action.

Foremost among them is Alpha Team Assemble (ATA), an outfit that has received much media attention in recent months for its combat training sessions and worrying statements of intent. As HOPE not hate can reveal, a number of far-right activists have also inveigled their way into the group, raising questions over its future direction.

ATA surfaced on Telegram in December 2021, adopting an alarmist tone and promising “no more words just pure unadulterated defiance”, as well as a “global war against governments”. It quickly amassed a sizeable following online, gaining over 8,000 subscribers on its Telegram channel, alongside 20 local groupings.

Instructing attendees to wear black clothing, ATA’s first event drew several dozen activists for a “self defence training session” in a park in Leeds on 19 December. It was followed by a meeting nine days later in Littlehampton, at which roughly 100 individuals performed combat drills. The biggest meeting so far took place in a park near Walsall, on 8 January, at which an estimated 200 people gathered and were subjected to drills by Danny Glass, founder of the group and a former Royal Fusilier.

After extensive negative press attention, ATA has toned down its public rhetoric, voicing its intent to operate within the law and that any obvious displays of “racism, bigotry or hate” online would result in bans. Despite these words, however, some marginal far-right activists have successfully inserted themselves into the group.

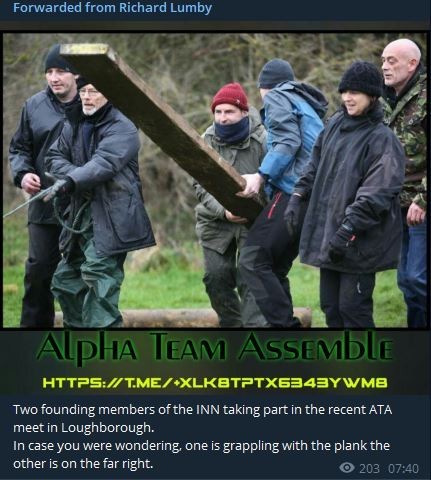

Among these figures is Richard Lumby, a former British National Party organiser and now the unofficial leader of the Independent Nationalist Network (INN), a small group that split away from Patriotic Alternative (PA) in 2021.

Lumby told INN members in January that the group’s “main direction” would be “the resistance against the global cabals”, promising to “get involved in the groups that are taking it to them, particularly on the vaccine issue, the COVID-passports etc.” To this end, INN members including Lumby and former PA activist “Anglo Joe” attended the ATA meet in Staffordshire in order to “make connections”.

On 15 January, Anglo Joe wrote in INN’s small internal chat group that he had: “Just got off the phone with Danny Glass, really positive stuff”, claiming that they had “agreed to move forward shoulder to shoulder”. Glass subsequently joined INN’s internal chat, stating that he was “not a political person at all but feel it’s time for all of us to connect and support each other”. After a series of friendly messages, Glass invited members to attend a future meet in the Midlands: “Be good to see the blokes that came to our last one and please bring some friends, and the honour you showed us by standing with us and saying what you did […].”

Such links are concerning in light of the unalloyed extremism of some figures associated with INN. For example, a recent addition to the group is the Dudley-based Andrew Barnes, who identifies as a lifelong National Socialist and has previously expressed support for a number of nazi terrorist groups, including Atomwaffen Division (described by Barnes as “the way forward”) and National Action (described by Barnes as “excellent”), both of which have been banned in the UK under anti-terror laws. Barnes has also agreed that the Christchurch killer Brenton Tarrant is “a good lad” and has expressed support for the nazi-satanist network, the Order of the Nine Angles (O9A). In February, Barnes joined ATA chat groups and inquired about any forthcoming meet-ups in Dudley.

Whilst INN remains a tiny group, more significant far-right outfits are making overtures towards ATA. For example, ATA’s East Midlands chat group has been repeatedly spammed with the propaganda of Patriotic Alternative, the largest and most active fascist organisation in the UK, including encouraging members to “get involved today”.

More worryingly, a number of ATA figures attended a January demonstration in Telford organised by Stephen Yaxley-Lennon (aka Tommy Robinson), with a number of members of ATA Telegram groups writing supportively of both Lennon and the event. “Tommy Robinson is a friggin hero”, stated one comment in ATA’s West Midlands group, with another claiming: “He’s the heart of England. Fuckin brave man.”

Although it is unclear whether far-right elements will exert any meaningful influence on ATA, the group is still in its infancy and is currently aiming to establish small groupings of dedicated activists, rather than a mass movement. The evident far-right sympathies within ATA are concerning, especially as the group may yet morph into more clandestine – and potentially more dangerous – iterations.

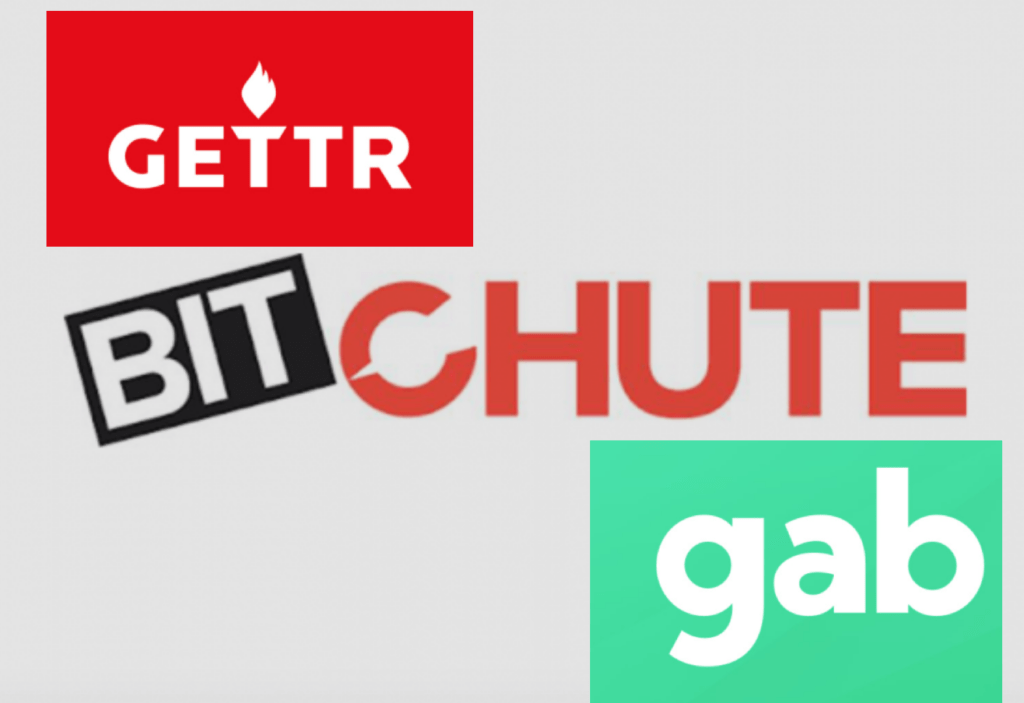

As deplatforming has increased, far-right activists have moved across to alternative social media platforms. Should we be worried? Possibly, says Joe Mulhall.

In October 2021, the former chief spokesman for Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign, Jason Miller, travelled to Europe for a meeting. At lunchtime on Tuesday 21 October, at the Spreegold restaurant in Berlin, he was joined by several other figures.

These included Lutz Bachmann and Siegfried Daebritz from the German anti-Muslim group PEGIDA, well-known anti-Muslim agitator Stephen Yaxley-Lennon (aka Tommy Robinson) from the UK and Matthew Tyrmand of the US-based far-right activist group, Project Veritas. They met, according to the far-right website Gateway Pundit, to plan the “defence of the West”.

Jason Miller had travelled across the Atlantic to encourage some of the best known far-right extremists in Europe to join his new social media platform, GETTR. A few weeks later Matthew Tyrmand, his international co-ordinator, described the purpose of GETTR as a “right platform for ideas to proliferate and to win in the battle of ideas and help save western civilisation”.

Before the meeting had even ended, Stephen Yaxley-Lennon made a video encouraging his supporters to join the new social media app: “I’ve asked lots of questions today to know that it is going to be a free speech platform that we can all use, so watch this space.”

In another message on his Telegram channel, he said: “I’m loving this platform. No censorship, seamless, and big things coming down the road. The future is brighter at Gettr. A real alternative to the censorious far left echo chamber known as Twitter.”

By 22 December Yaxley-Lennon had accrued 50,000 followers on the new platform, rising to 100,000 by 4 January, 150,000 by 14 January and by February this year he had reached over 180,000 followers. This was in addition to his 155,000 followers on Telegram and 28,000 subscribers on the video sharing platform BitChute. In one GETTR livestream he excitedly said: “Just watch the numbers continue to rise on the alternative platforms, we’re getting our voice back.”

While significantly less than the one million followers he had on Facebook back in 2019, Lennon’s rapid growth on alternative social media platforms begs the question whether so-called ‘alt-tech’ has finally become a genuinely viable option for the deplatformed far right?

In recent years far-right activists and movements have been faced with an increasingly important problem: namely, being hugely dependent on internet platforms while not being in control of them. For most of the postwar period far-right activists were actively marginalised from mainstream discourse, making it difficult for extremists to reach large audiences.

For this reason, the far right were enthusiastic early adopters of the internet, quickly seeing it as an opportunity to disseminate their ideas while bypassing the gatekeepers of the mainstream media. The subsequent advent of social media afforded them previously unimaginable opportunities: not just the dissemination of information to huge new audiences, but also providing a means by which to network within a movement and across ideological and national boundaries.

However, following numerous waves of deplatforming and increasingly effective content moderation practices on the more mainstream social platforms, far-right activists once again found themselves being marginalised from public debate.

With this increasing marginalisation, far right figures began to migrate to alternative and usually smaller platforms, but still eventually finding themselves removed or falling into obscurity. The solution appeared obvious, if not simple: they needed to create their own alternative technologies that they used and also controlled.

The result is that there are now broadly three categories of social media platforms used by the far right.

The first are mainstream platforms: those that are widely used by all across society, such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Youtube and TikTok. While these platforms all have an extremism problem, they generally have terms and policies that prohibit extreme and discriminatory behaviour, even if they don’t always enact them as consistently as necessary. Where possible the far right want to remain on these platforms, as they afford huge audiences beyond existing supporter bases. This is where they want to propagandise and recruit.

Next are co-opted platforms: those not created for or by the far right, but which have become widely used by them, either because of loose policies, a lack of moderation, or a libertarian attitude towards deplatforming and content removal. Most notable is Telegram, which is an enormous social media app with over one billion downloads globally. Due to its consistent failure to remove extremist activity, it has become a crucial hub for the contemporary far right. The danger for the far right with these platforms is that they may eventually choose to clean up their act and remove illegal or harmful content, making them insecure homes in the long term.

The final category is bespoke platforms: a growing group of platforms, created by the far right or by people consciously courting extremists. Many of these are essentially clones of major platforms, but featuring little or no moderation. The best known are Gab, BitChute and most recently, GETTR.

For some on the far right, particularly those who have been widely deplatformed, alt-tech platforms are replacements, as close to a straight swap as they can manage. Gab and GETTR replace their deleted Twitter accounts, while BitChute or Rumble replace their lost YouTube channels.

However, for many of these people, alt-tech is supplementary. They use an array of platforms simultaneously and for different purposes. Take the fascist group Patriotic Alternative (PA), for example. Before a recent set of bans, they used Twitter, Facebook and YouTube to propagandise and recruit, while simultaneously employing Telegram, BitChute and DLive for organising or presenting more extreme content. The group used a range of platforms simultaneously and for different purposes, with activists consciously adopting a different tone for each.

While not new (the far-right Reddit alternative Voat was launched back in 2014), the creation of alt-tech and bespoke far-right platforms has not, generally, been successful. Most have had short lifespans and soon collapsed, or lapsed into semi-dormancy. Even the ones that have survived have suffered from far-right ghettoisation.

Part of the appeal of social media for the far right was the ability it afforded them to attack victims, as well as troll “normies”, plus propagandise and recruit new activists. While their own platforms provide a safe-haven of sorts, the possibility of unmoderated speech is not enough of a reason, in itself, to continue to engage.

Other issues are more practical in nature, reflecting the quality of the platforms themselves. The polish of mainstream services like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube has ultimately made the general user picky and impatient when it comes to competing platforms; the user experience on alt-platforms is noticeably worse than mainstream alternatives.

There is also the issue that even so-called ‘free speech platforms’ invariably have to remove some illegal speech. While many often don’t, the ones that are looking to attract larger and (somewhat) more mainstream audiences will begin to do so, at which point their core users may begin to feel betrayed.

All of this is compounded by the issue that a well-constructed platform is of no use if the domain name is seized or its hosting is shut down. That’s why a question remains: who controls the infrastructure services on which the modern web relies? That still remains a hurdle for the many in the extreme right.

However, while many of these issues remain a problem, the last few years have seen the emergence of a far more viable alternative online space for far-right activists. Whether it is video sharing platforms such as BitChute or Odysee, or Twitter clones like Gab or GETTR, the quality, reliability and user experience has increased dramatically.

Prominent figures such as Stephen Yaxley-Lennon, who already possess an international following, have managed to build up significant followings on these alternative platforms. Yaxley-Lennon regularly livestreams on GETTR to thousands of people all over the world, something not possible since being deplatformed by Twitter in 2018.

Thankfully most other UK far-right groups and individuals have continued to struggle to build large audiences on alternative platforms, especially the thuggish anti-Muslim group Britain First, which once had more than two million likes on Facebook but now have under 2,000 followers on GETTR.

While debates continue to rage about the efficacy of deplatforming, it is still the case that the far right will reach far fewer people on alt-tech platforms than they did on major social media outlets. However, over the last few years, the alt-tech online space has developed rapidly and is becoming an increasingly viable alternative – something that should worry us all.

In a year when an official Government report claimed that there was no institutional racism, black and ethnic minority Britons found racism and discrimination all too commonplace. Rosie Carter reports.

The reality of life experienced by black and ethnic minority Britons in 2021 is quite different from that given in a report commissioned by the Government as its response to the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement in 2020.

The Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities, chaired by Tony Sewell and which published its report in March 2021, rejected the premise that the UK had a systemic problem with racism and claimed that it should be a “model” for other countries in their response to racism. Yet polling conducted by Focaldata on behalf of HOPE not hate over the Christmas period, shows that this rosy picture of racial relations and racial harmony is not shared by the majority of Britons of black and ethnic minority heritage.

It is no great surprise that in our poll, the majority of people from black and ethnic minority backgrounds see that black and Asian people face discrimination in their everyday lives (67% agree), with female respondents more likely (72%) than male respondents (61%) to agree, highlighting different intersectional experiences.

Black and black British respondents are also most likely to say that black and Asian people in the UK face discrimination in their everyday lives (75%) than Asian and Asian British (65%), or those who saw themselves as of mixed or multiple heritage (72%), and those from other ethnic minority groups (51%), highlighting the engrained and explicit nature of anti-black racism in the UK.

Our poll is the third we have done in the last two years. Our first was commissioned in the summer of 2020, in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic and as the country was gripped by the emergence of the BLM movement.

In January 2021, we revisited some of the same questions, to look at how, if at all, things had changed, and found support for the BLM movement had sustained, and the movement had had a huge impact in changing the conversation on race and racism in Britain, in particular in raising consciousness of anti-blackness. But we also found widespread disappointment around the Government’s response to BLM, and cynicism around their pledges to address racism in Britain.

The polls were designed to better understand the mood of Britons of back and minority ethnic heritage, often poorly represented by small sample sizes in national polls, and to pick apart differences in opinion between ethnicities, heritage backgrounds and religion.

Our initial poll reflected how the shared experiences of being a minority fostered a mutual empathy and solidarity, with the differences between ethnicities and generations reflected in how people understood and expressed common experiences of discrimination and racism. We saw support for the BLM movement across ethnicities and age groups, with widespread optimism and expectations for change that the protests would lead to lasting improvements for ethnic minorities in Britain, particularly among younger BAME Britons.

In January 2021, we revisited some of the same questions to look at how, if at all, things had changed. We found sustained support for the BLM movement, which had had a huge impact in changing the conversation on race and racism in Britain, in particular in raising consciousness of anti-blackness. But we also found widespread disappointment around the Government’s response to BLM, and cynicism around its pledges to address racism in Britain.

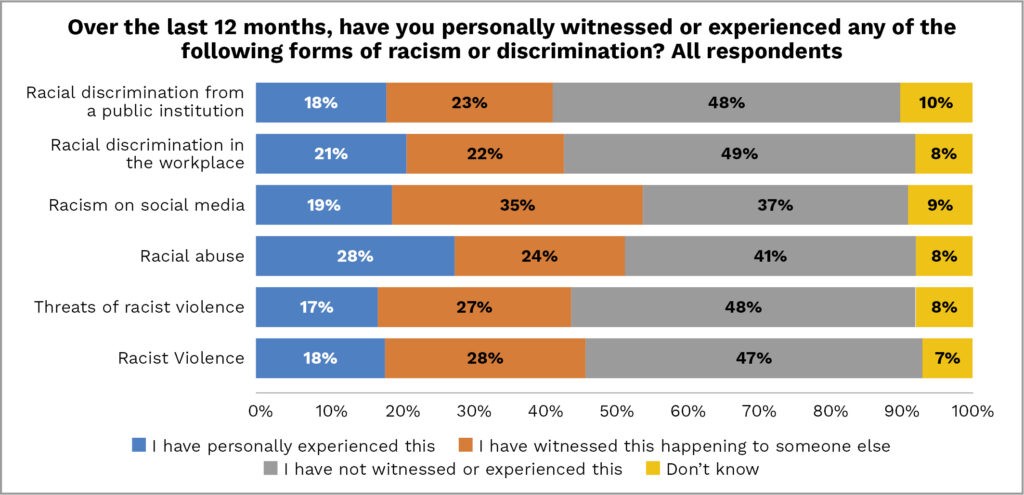

A year on, we have repeated our poll. The results would seem to suggest there has been an increase in racist violence, abuse and racism in the workplace and public institutions over the last year. Overall, 18% of respondents said they had personally experienced racist violence during the past year, while 28% said they had witnessed it. In our poll from January 2021, 11% of respondents reported having experienced racist violence, while 16% had witnessed it, and 13% had both witnessed and experienced racist violence over the previous 12 months.

And overall, just as many respondents had experienced racist violence directly (18%) as had experienced threats of racist violence (17%), while almost a third (27%) had witnessed such violence.

More than half of respondents (52%) had witnessed (24%) or experienced (28%) racial abuse in the last 12 months. And while experiences of racially aggravated violence were higher among 18-24s, racial abuse was experienced and witnessed by large numbers across all age groups.

The usefulness of the administrative term ‘BAME’, is highly contested, and often hides the heterogeneity of ethnic minorities, and fails to capture the complex reality of identities. However, we specifically sampled individuals under the ‘BAME’ banner, not only because is polling standard to do so, but this was the only way that we are able to poll representative samples of ethnic minority people from different backgrounds in order to ensure the heterogeneity of different groups was represented.

Among 18-24s, fewer than a third (32%) of respondents could say they had neither witnessed nor experienced racist violence in the last 12 months; 43% said they had witnessed this happen to someone else, but one in five (20%) said that they had personally experienced it. And more than one in five male respondents said that they had personally experienced racist violence in the last year (21%), while 15% of female respondents said the same. The highest reports of personal experience of racist violence came from respondents in the North East (28%), Yorkshire and Humberside (29%).

The depth of explicitly anti-black racism and anti-Muslim prejudice is profound. Black and mixed race respondents were both more likely to report having personally experienced racist violence (21-22%), while around one quarter of BAME Muslim respondents said that they had personally experienced racist violence in the last 12 months (23%), and 30% said that they had witnessed racist violence towards another.

Despite 10 years of attempts by social media companies to regulate and moderate hate speech, and statements that they would do more to address racism and support racial justice following the global response to George Floyd’s murder, our poll finds that overall one in five (19%) respondents had personally experienced racism on social media, while more than a third (35%) had witnessed it. Among young people (18-24s), 27% had personally experienced racism on social media and half (48%) had witnessed racism online.

And overall, despite many working from home as a precaution to stop the spread of COVID-19, fewer than half of respondents said that they had not experienced racial discrimination in the workplace (49%). Just as many said they had not experienced racial discrimination from a public institution (48%). Again, Black Britons were most likely to have personally experienced racial discrimination in the workplace (28%) or from a public institution (23%) than respondents of other minority ethnic heritage.

Depressingly, 2021 has been another year of empty promises to take action on racism, putting to shame the Government’s claim of outright rejection of institutional racism, and Britain’s claim to be a model when it comes to addressing racism.

More than two years since the killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer sparked a global movement against police violence and structural racism, the impact of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement in the UK remains significant to Britain’s black and minority ethnic populations.

Support for BLM has remained constant during this time, and a majority of respondents in our poll (59%) maintained that the BLM movement spoke to their concerns about racism in Britain – just 14% disagreed. Black respondents were most likely to feel their concerns were represented by the BLM movement: 77% agreed, while just 8% did not feel represented.

Black respondents were also more optimistic about the impact of the BLM protests – half (50%) agreed that they had led to lasting improvements for ethnic minorities in Britain, compared to 45% of all BAME respondents. And black respondents were slightly more likely to think that white people had taken racism more seriously after the protests (51% agreed with this statement). Overall, 49% of BAME Britons felt that white people had taken racism more seriously after the protests.

At the same time, there was a strong feeling that many white people had responded poorly. Half (51%) agreed that white people often played the victim when called out for racism, while a third were unsure (34%) but only 15% disagreed. Black respondents were most likely to agree that white people often played the victim: 63% agreed, with more than a third (36%) in strong agreement.

After the last General Election in 2019, just 10% of Members of the House of Commons and only 6.6% of Members of the House of Lords were from ethnic minority backgrounds, both of which are below the overall proportion of the population. Perhaps it is unsurprising, then, that just a quarter (25%) of respondents agreed (and just 7% strongly agreed) with the statement “people like me are well represented in political discussion”. Female respondents were even less likely to feel represented: just 21% agreed, with 6% agreeing strongly (29% of male respondents agreed and 9% of those strongly).

But there are many other reasons for people of black and minority ethnic heritage to feel that they are not well represented in politics. While the far right’s electoral success has sharply declined in recent years, racism within the main political parties has become a focal point of national discussion, including explicitly anti-Muslim prejudice in the Conservative party and antisemitism in the Labour Party.

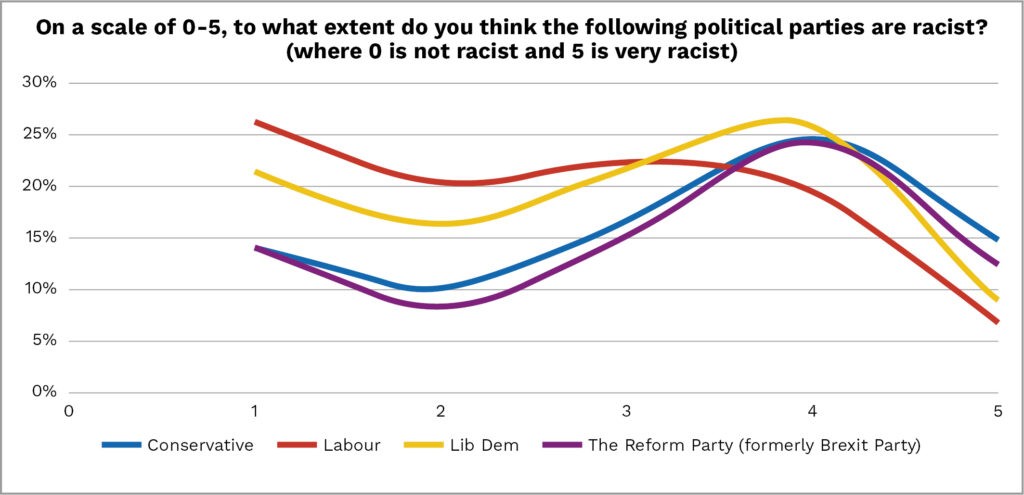

When our poll asked how racist each person perceived the main political parties to be, respondents generally saw Labour as the least racist party, while the Conservatives and Reform parties were seen as more. In fact, more respondents felt that the Conservative Party was “very racist” than the Reform Party (formerly Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party).

Policies may have had some sway here, including Priti Patel’s hardline stance on immigration, and in her attempts to pass the new Nationalities and Borders Bill. Clause 9 of the bill is causing particular controversy, as it means six million people with dual nationality, or who were born outside the UK, could be stripped of their British citizenship without fair warning. Post the Windrush debacle, this would most likely impact Britons of black and minority ethnic heritage, sending a message that those who are not white and British do not hold the same sense of belonging in the UK. More than a third (38%) of our poll agreed with the statement: “The British immigration system is racist”, though 37% neither agreed nor disagreed, and a quarter (25%) disagreed.

Moreover, the impact of Islamophobia exposed in the Conservative Party has clearly stemmed their appeal with Muslim voters. More than one in five (21%) of Muslim respondents scored the Conservative party a 5 (very racist). Recent allegations by the Conservative MP Nusrat Ghani that she was sacked from a ministerial role for being Muslim have revived calls for action against Islamophobia in the party.

HOPE not hate’s polling from Autumn 2020 found that found that almost half of Conservative Party members believed Islam was “a threat to the British way of life”; more than a third of card-carrying Tories also believed that Islamist terror attacks reflected a widespread hostility to Britain among the Muslim community; and nearly six in 10 thought “there are no-go areas in Britain where sharia law dominates and non-Muslims cannot enter”.

Indeed, until parties are ready to take meaningful action on racism within their own ranks, people of black and minority ethnic heritage will continue to feel misrepresented by our political system.

When asked about the impact of the pandemic, it is clear that many people from BAME backgrounds are struggling.

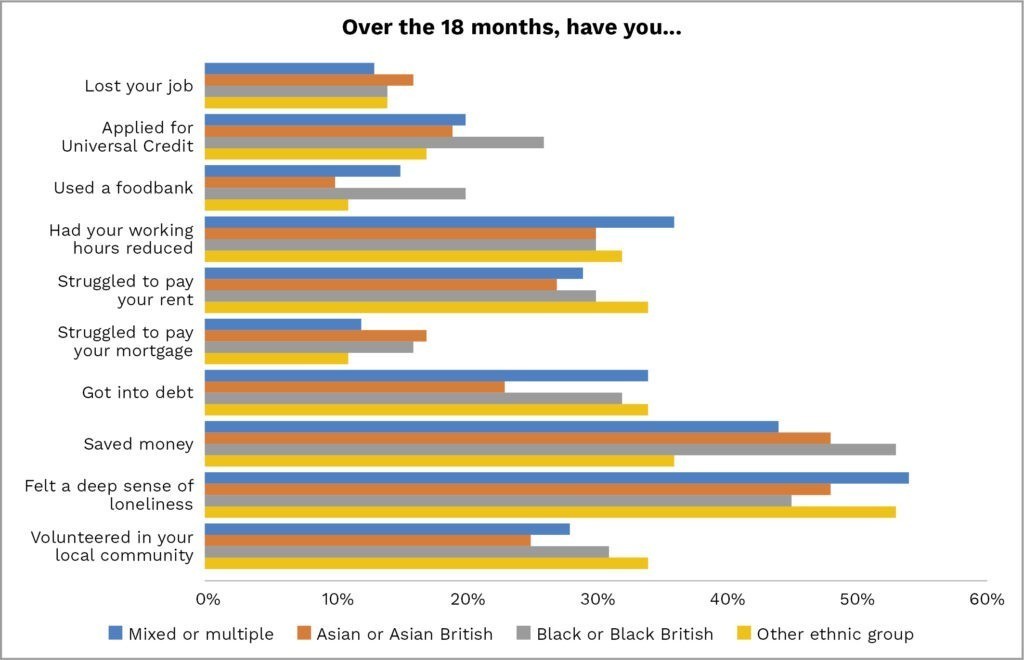

The financial impact of the pandemic has disproportionately impacted people from BAME communities. When we carried out comparative polling in early 2021, more than a third of BAME respondents were more likely to say they had had their hours reduced, lost their job, or struggled financially to meet basic living costs, and black respondents were twice as likely to say they had applied for Universal Credit than white respondents, and more than twice as likely to say that they had lost their job than white respondents.

A year later, the impact of the pandemic on people from BAME backgrounds has, if anything, worsened. The vast majority are feeling the pinch, with three quarters of respondents (74%) saying that they had less disposable income after housing, food and fuel than a year ago. Only a quarter (26%) said they were doing better.

More than a quarter (26%) of black respondents also said that they had applied for Universal Credit, while one in five (20%) said that they had used a foodbank in the last 18 months. Sixteen percent (16%) of respondents who described themselves as Asian or Asian British said they had lost their job in the last 18 months, while around a third of people across different BAME backgrounds said they had seen their working hours reduced or struggled to meet rent or mortgage payments.

With the cost of living rising substantially, all of these impacts will be felt even more, with people from BAME backgrounds more likely to have disproportionally high living costs as they are more likely to pay a ‘poverty premium’, more likely to be in precarious and low-wage work, private rental accommodation, and more restricted or costly access to credit, banking and insurance.

Clearly, action needs to be taken to build security for those facing the sharpest effects of the pandemic, and the disproportionate impact for people from BAME backgrounds must be addressed.

Methodology

Focaldata’s polling of 1082 respondents of black and minority ethnic heritage carried out between the 17 December – 04 January 2022. Data was weighted to be nationally representative of the GB BAME adult population – weighted to age, gender, region, ethnic group, and religion.

Matthew Collins discovers the conspiracy theorists and far-right politicians behind the Workers of England Union.

In normal circumstances, it might appear unusual if a trade union received an endorsement from the Eurosceptic Brexiteer think tank, the Bruges Group, who count amongst its past and current presidents union busters Margaret Thatcher and Norman Tebbit.

But that’s the situation with the Workers of England Union (WEU), a union that has become increasingly popular with anti-Vaxx activists and even the far right self-declared ‘migrant hunters’. With the WEU heavily dominated by the English Democrats, the endorsement of the Bruges Group is not such a strange endorsement after all.

The Bruges Group has commended the WEU’s campaign to recruit care home workers affected by the November 2021 mandatory vaccination law, which made it mandatory to get a COVID-19 vaccination before entering a care home in a professional capacity.

According to the Bruges Group “the large trade unions and professional associations have failed to protect their members from the threat of dismissal. In fact, Unison and the Royal College of Nursing support vaccination in the belief that it protects patients and staff. This is despite mounting evidence that infections occur as frequently in the vaccinated as in the unvaccinated.”

The Bruges Group produce no hard empirical or scientific evidence to back this up this claim, though there are of course plenty of faux scientists on social media that espouse similar views.

The Bruges Group has found likeminded fellow travellers in the WEU and this is most definitely not in the long term interests of working people, as both it and the WEU are invested in attacking and trying to undermine the established and Trade Union Congress (TUC)-recognised unions.

Followers of WEU on its Facebook page claim they have been encouraged by the vaccine ‘exemption certificates’ distributed by the union. The WEU is at pains to point out that this is a ‘self-certification’ certificate which doesn’t actually state why the certified person is exempt. It is therefore unclear what actual legal rights they carry, if at all, unless the employer feels forced to accept it.

There are health authorities who are currently refusing to recognise these self-certification certificates. One authority in particular has refused to bow to the WEU: Rotherham Doncaster and South Humberside NHS Trust. The Trust employs some 3,700 people in mental health and learning disability services, as well as district nurses and health visitors – frontline staff confronting the reality of COVID head on.

The WEU claimed in late January that the Trust had “consistently failed to state why WEU members Self-certificate [sic] isn’t compliant” and even suggested that the its refusal was evidence enough to show “it [their self-certification certificate] is compliant” (with government legislation).

However, it is in the sections of the health industry without strong legal and scientific guidance where the WEU appears to have been most active. It has issued threats to employers in care homes with small numbers of employees, often working under conditions and contracts established with recognised unions such as Unison, GMB and Unite.

In the run up to and post-the government legislation last year, the WEU issued a standard DIY warning letter for “NHS Trust employees and those in the health sector but not employed by an NHS Trust” to send their employer a warning they would not enter into discussions about being either vaccinated or about their future employment.

The caveat is of course in the small print from the website where these letters can be downloaded: “neither the above nor any information posted on this website constitutes legal advice. It must not be relied upon as such and specialist legal advice should be taken in relation to specific circumstances” .

This is in stark contrast to the larger trade unions, which do offer verified legal and health advice. Much of WEU’s advice, it declares, simply comes from “non-clinical” NHS staff.

The WEU has thrown its weight behind an increasingly unstable and bewildering anti-vaxx and anti-lockdown movement. Much of this movement is anti-scientific and driven by fear, conspiracy and confusion. The WEU has even taken out advertisements in such places as The Light Paper, whose founder is an exponent of the Flat Earth conspiracy theory.

As well as baffling employers and others with a myriad of faux science and legal jargon, the WEU has pushed the idea of non-existent rights of employees under spurious notions of “common law” which, according to the WEU’s General Secretary Stephen Morris, has been around for “1700 years”.

Our own advice, from a proper employment law solicitor, is that this is a dangerous and harmful tact. Common Law is simply a development through procedure and has absolutely no precedent over laws passed by Parliament. Neither do “English law”, the Magna Carta or “Roman Law”, all of which the anti-vaxx and anti-lockdown movement, to varying degrees, rely upon to intimidate and confound vulnerable people.

Conspiracy and far-right extremism are nothing new to either the WEU or the English Democrats, its alma mater.

The WEU first came to our attention more than a decade ago, as the sidearm of the English Democrats (ED). The ED had gone from the absolute fringe of the far right to become the bolt-hole for former British National Party (BNP) members. Some 400 former British National Party (BNP) members, including Eddy Butler and Chris “I don’t hate Hitler” Beverly, a former BNP councillor from Leeds, took up prominent positions in the ED after leaving the BNP.

Writing in May 2012, HOPE not hate noted the ED had “recently established a trade union-wing, the Workers of England Union (WEU), which was originally conceived in 2005 but eventually launched on 7 September 2009.”

The WEU claims not to be related to any political party or movement, stating its aim is to protect, support and represent all working people in England. It pledges to campaign for English workers against cheap foreign labour and to represent the “indigenous” English.

The use of threats, fraud and intimidation are hardly foreign concepts to the parent party, the English Democrats. As well as being linked with the dubious former BNP fundraiser Jim Dowson and his ‘Midas’ fundraising enterprise, in 2017 the deputy leader, Steve Uncles, was jailed for electoral fraud after submitting fake nomination forms.

The English Democrat leader, Robin Tilbrook, is also the in-house solicitor for the WEU. He has 15 directorships listed with Companies House in London, including Trade Union Congress for England, Confederation of English Business, and ‘Lawyers for Liberty’, for which only Tilbrook is listed as Director and is also listed as ‘dormant’.

Lawyers for Liberty was cited by Private Eye as last year as being behind an anonymous campaign to encourage parents to fill in complaint forms about schools that required students returning after “the great lockdown” to wear masks. These complaints were then followed up by legal-looking letters from the aforementioned Lawyers for Liberty, where the small print once again was far more revealing. “Lawyers for Liberty are not a law firm” it said, and the legal-looking letter of complaint “should not be construed as legal advice”.

Other legal ventures launched by Tilbrook have included ‘The People’s Brexit’, which in 2020 crowdfunded £80,000 in an attempt to overturn the Coronavirus Act 2020 and all lockdown rules. While Tilbrook’s own legal firm owned the case, the QC who signed off some of the legal letters was Paul Oakley QC, the former immigration spokesperson for the UK Independence Party (UKIP).

The WEU laughingly claims it is “not affiliated to any political party”. And although it is true that the English Democrats – like Workers of England Union – rarely function in the manner their name should suggest, it is disingenuous bordering on dishonest to even suggest WEU is not another front for the dishonest activities of the ED.

The General Secretary of the WEU is Stephen Morris, a perennial losing candidate for the ED in Greater Manchester. A former branch official for Unite, Morris has based the WEU in a tiny office near his home in Bury, Lancashire.

It is concerning that Morris and the WEU have targeted the health sector while it is already under great duress, not just from government cuts, overwhelming COVID admissions to hospitals, but also the constant threat the NHS faces from private profiteers.

In a 2017 flash interview for the BBC as part of his candidature for Manchester Metro Mayor, Morris stated he wanted “social health care with a business strategy”, among other things.

The WEU 2019 returns to the certification officer showed the union had only 1197 members and an income of £116,000. Over £89,000 of that income was spent on administrative costs, just under half of which was salaries. It showed a mere benefit to members of £6,000.

Earlier this year, the Press Association news wire service won an injunction against the WEU, after complaints from HOPE not hate and the National Union of Journalists, for issuing press cards to “citizen journalists” – a social media phenomena of untrained and unregulated ‘news gatherers’ who were attempting to use and abuse the privileges afforded to those with properly accredited press cards.

The use of these fake cards came to the attention of anti-fascists when a number of far-right activists produced WEU press cards while attempting to antagonise real journalists and trade unionists covering far-right demonstrations and gatherings.

The fake ID cards were issued by the WEU under the guise of the ‘English Press Association’, which does not exist except under the auspices of the WEU. The card could be considered solely for the benefit of people who spread conspiracy theories and fake news on social media.

The High Court heard the cards were “instruments of deception” which allowed WEU members to “misrepresent themselves as being affiliated with or employed by PA”. Seventeen members of the union had bought these cards, despite there being no evidence that any were engaged in professional journalism.

The WEU was represented in court by Robin Tilbrook, who described himself as the “Chairman of WEU”, even though it had “no party political affiliations”. The court heard the WEU was considering using the name ‘English Media Group’ in future. Interestingly, though not entirely surprisingly, the ‘English Media Group’ surfaced late last year when far-right fellow travellers Alan Leggett, Nigel Marcham, Steve Laws and Tracey Wiseman were in court in Dover for their activities related to refugee arrivals. Laws is better known as “the migrant hunter” and Marchman as the foul-mouthed reprobate “the tiny veteran”. Again, the WEU described all four as “journalists”. They are not.

People who are members or supporters of the WEU appear to be either delighted by being represented by self-certification and common law, or frustrated by their inability to contact either the union or representatives.

The WEU is part of a concerted conspiracy to confuse workers, bully vulnerable care home employers as well as working to undermine the sanctity of both journalism and the trade union movement. It is no surprise it is not a member or affiliate of the TUC, where it would be open to scrutiny, regulation and proper legal and employment training. Instead of inconvenient or unpalatable facts, it relies upon the strength of fear and conspiracy and sadly, the patronage of racists.

The Workers of England Union is also affiliated to the Taxpayers Alliance (TPA), another libertarian, anti-union organisation, which supports the slashing of public services and massive tax cuts for the rich. Amongst the policies of the TPA are freezing all welfare benefits for two years, scrapping national pay bargaining in the public sector and abolishing the pensions ‘triple lock’.

By supporting, or having the support of, such organisations as The Bruges Group and TPA, the WEU is no friend of public sector workers.

Patrik Hermansson charts the growth of fascist fitness groups.

Fitness advice is a growing focus for the far right in Britain and internationally. The “fitness” subculture is a potential entryway into far-right groups and radicalisation. While once a staple of 4chan’s /pol/ board, more recently explicitly fascist British fitness groups have grown in popularity on chat app Telegram, and active communities have sprung up focused on the topic. Some of the largest are directly connected to Britain’s largest extreme right group, Patriotic Alternative.

The language in these “fascist fitness” chat groups is often indistinguishable with that on any other fitness blog or Instagram post: increase your protein intake, avoid bread, work out regularly, and sleep properly.

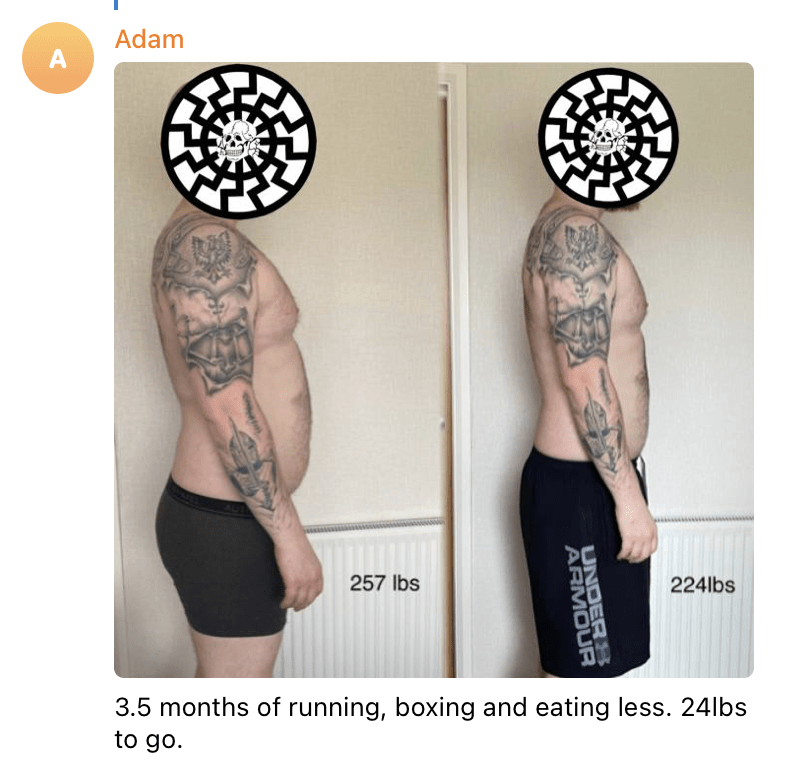

The tone is encouraging and accepting when members post images of their half-naked bodies, and ask for advice on both how to lose weight and gain muscle. Some look like avid gym-goers; others have just started and want to lose weight. Despite being far away from what one imagines as the “ideal” of the fascist man, these individuals are encouraged and welcomed into the closed chat groups in which fascist fitness activists congregate.

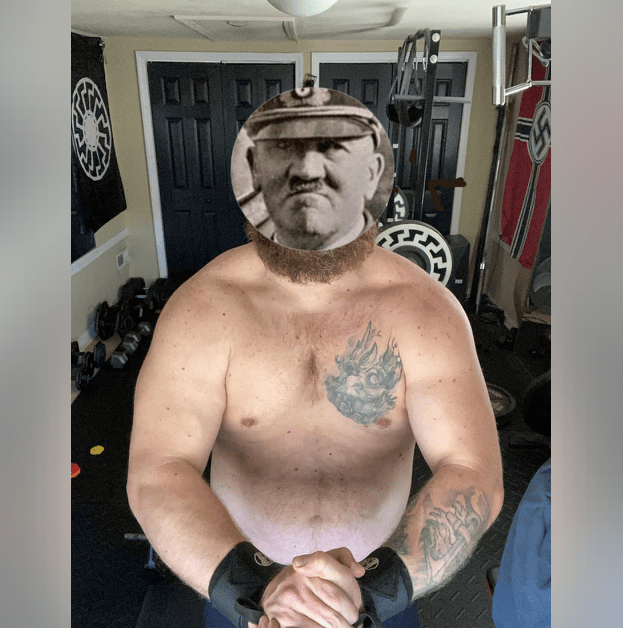

However, the photos of bare torsos are usually anonymised with stickers of Hitler’s face over each poster’s face, and between the fitness and weight loss advice is sandwiched the fascist propaganda. Both texts and promotion of far-right groups such as Patriotic Alternative (PA) are common. In other messages, more sinister reasons for the self-improvement projects reveal themselves. One admin of a group posted a picture of himself in a gym mirror with the message: “training to stop a bus loaded with Soros paid protesters”.

“Ready to join the SS,” writes one anonymous user after posting a shirtless picture of himself in the gym mirror. Other posts detail workout plans alongside questions on how to make improvements. One man posts before and after pictures of himself, saying: “Currently weight 279 so in total I’ve lost 25 lbs” and receives encouraging responses from the other members, including: “NEVER STOP. SIEG HEIL.”

The tone is accepting towards group members, but virulently hostile to political opponents. “I hate soy boys. Vegetarianism is an eating disorder,” writes one user, using the pejorative term “soy boy” to refer to other men who supposedly lack masculine characteristics. It’s common to see accusations of other men also being “low T”, meaning having low levels of testosterone. Physical fitness in these groups is not just about the individual, but a way for the members to differentiate themselves from what they view as a “weak” and “effeminate” political establishment.

Since its inception, fascism has defined itself in opposition to what it views as the decadence as well as “softness” of modernity. Instead, fascist groups and individuals have promoted physical strength, glorified struggle and underlined traditional gender roles – to counter what they view as the feminisation of men. This conspiratorial world view imagines that a supposedly softened and disorganised society opens up to the influence of sinister forces, and to resolve a healthy, physically and mentally strong population is required in response.

Ultimately, in the fascist view, the health of the nation is defined by the health of its people and how closely these reflect the ideals of purity and strength. At its worst this process leads to purging of what fascists consider impure groups: non-whites, those with disabilities and other examples of what they consider “degeneracy”.

Mussolini famously glorified violence and favoured it above reason and debate, answering a question about what his party programme was in 1920 by saying: “The Democrats of Il Mondo want to know our programme? It is to break the bones of the democrats of Il Mondo. And the sooner the better”. Oswald Mosley and his British Union of Fascists (BUF) emphasised the importance of physical fitness of its members. The party organised sports clubs and its members’ magazine Action ran a weekly column called “How to Keep Fit” with fitness advice. It advocated for a reshaping of the educational system with a new emphasis on fitness, Mosley wrote in Action that from age seven to 14, school would “mainly be devoted to physique building and medical supervision”. Another issue from 1938 read: “Right up to the age of 18 the duty of building a child’s body will be as great a preoccupation of the nation as the building of its mind”.

This connection between the health of the nation and its people remains today. Researcher on the far right, Ben Elley, argues that in far-right self-improvement groups, personal fitness is not just for one’s own benefit but is part of a political struggle. By becoming physically stronger they believe they can prevent the white race from being destroyed. Elley writes that self-improvement “become part of a righteous Manichean battle, greatly distorting the balance of input and reward that might normally be expected. Small personal victories […] are incentivised as victories on the cultural battlefield”.

Fascist fitness groups on Telegram conceptualise their members’ bodies as a battleground. The group’s members urge each other to get more physically fit by lifting weights and exercising and making such exercise part of their far-right activism. “When you lift alone, you lift with Hitler”, one admin writes. It adds meaning to what would otherwise be a purely individual project. When viewed as part of a political project, lifting weights is a way to become a “hero” through pain and struggle.

This worldview is gendered, of course. German sociologist Klaus Theweleit argued that part of the fascist attraction to hardening oneself physically as well as mentally came from “misogyny or flight from the feminine, manifesting itself in a pathological fear of being engulfed by anything in external reality associated with softness”. Several fitness-focused far-right groups only allow men as members and in Telegram chats, women are mostly relegated to a back seat, because femininity is what its members attempt to distance themselves from.

One of the groups which has gone furthest in its emphasis on physical fitness is White Stag Athletic Club (WSAC), which has approximately 30 members. Formed in the last two years by pseudonymous Yorkshire-based security guard “Sarge”, it seeks to “fight degeneracy through honour, tradition, and brotherhood”.

“Through this struggle, we forge ourselves into greater men,” its introductory message says. In 2021, the group amped up its recruitment efforts and started to recruit individuals via a Telegram channel. Sarge, who is also connected to Patriotic Alternative, is an administrator for another large fitness chat, which he has also used to recruit. Sarge previously went by the name “Ash” and was one of the co-founders of the fascist podcast The Absolute State of Britain, meaning there is little doubt of the new group’s ideological direction.

WSAC is an interesting case study because of its combination of fascist worldview with extreme emphasis on physical fitness alongside – in its own words – a rejection of organised politics as a way to effect change. Instead, it aims to produce hardened men and “better fathers than they had” themselves. Or so says Sarge, who claims to be a father to one child himself.

The tight-knit, secretive group organises local meet ups and aims to do a hike each year with all of its members. The hike is weighted, meaning participants have to carry a weighted backpack. This year’s hike took place on 15 January in Pen-y-ghent in Yorkshire. Alongside the hike, members are eventually expected to take part in fights with one other member, demonstrating the directly violent element of fascist fitness groups.

Throughout the year, members commit to doing a daily exercise programme designed by one of its leaders. This is updated regularly and published in a closed group on encrypted chat app Wickr. Once completed, members write “Hail Victory” in a closed chat group.

Despite its rejection of politics, WSAC’s fascism is demonstrated in the chat regularly. Members post pictures of swastika flags and when Kyle Rittenhouse, an American who shot and killed two anti-racist protesters in Kenosha, Wisconsin, on 25 August 2020, was found not guilty in November 2021 the group erupted in celebration. “Hail Kyle” posted multiple users.

Positioning physical fitness as part of a wider political struggle adds significance to an otherwise quite lonely activity, allowing groups like WSAC to form and grow around this shared identity and activity. This might be part of the reason why such groups have appeared and have risen in popularity during the pandemic. Disconnected physically, many have looked to online communities for connection, and when it comes to the far right, also ways to engage and push forward the aims of the movement under the constraints of social distancing restrictions. Physical exercise and self-improvement more generally can help satisfy the urge to do something practical, that goes beyond simply talking online, for the movement’s activists (while also being relatively low risk).

The danger of these groups lies, firstly, in their emphasis on transforming activists into soldiers that might be motivated to commit acts of violence. And, secondly, in the community they create where members start to associate, sometimes real, positive change in their lives with fascism.

An intrinsic part of the “self-improvement” message of these groups is to increase one’s capacity for violence. WSAC and many groups before it push their members not just to be physically fit but also to learn how to fight. In Telegram groups, American and European fight groups such as the Rise Above Movement (RAM) are often glorified. WSAC has also glorified RAM. Four members of RAM were arrested in 2018 for inciting and participating in violent acts against anti-racist protestors. WSAC’s requirement to take part in fights is inspired by international fight clubs like these.

However, direct violence is rarely the primary motivation for joining these groups, and the community aspect is central and one of their more sinister aspects. After observing fascist fitness groups for several months, it is undeniable that some of their members make significant steps towards their goals. Users like “Dan”, who joined one of the larger Telegram groups in July 2021, has regularly posted pictures of his progress and said he had lost 45 lb. Moreover, he has graduated from being a lowly member to becoming an administrator of the group and now posts almost daily. Associating, in their view, positive change in one’s life, with a violent and hateful ideology, is dangerous. Elley describes it as the member who achieves his goals become “indebted to the movement for his change”.

Fascist fitness groups provide community and purpose that might be hard for some of these individuals to find elsewhere. This has been exacerbated by the pandemic, and is unlikely to disappear once restrictions are gone. Relationships and communities have already been formed, catalysed by a frustration within many parts of the far right with purely online organising. Fitness, alone or in group, and even if imaginary, provides a directly practical way of doing something for the far-right cause.

Safya Khan-Ruf exposes how far-right activists are attempting to exploit antimigrant tensions.

Margaret Thatcher made this inflammatory remark in 1978. Fears over migration are not a new phenomenon in Britain. Forty-four years later, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson is still promising the country will not return to “uncontrolled immigration”. Meanwhile Home Secretary Priti Patel’s controversial Nationality and Borders Bill attempts to criminalise people who manage to reach the UK irregularly. The same Bill could theoretically also enable the deprivation of the citizenship rights of minority-ethnic Britons.

The Bill came into parliament as concerns grew over the number of people making the treacherous journey aboard small boats to the UN from the Continent, via the English Channel. More than 28,300 people used this route in 2021 – triple the number of the year before, according to Home Office statistics, but still a tiny number when compared to many other European countries. The highest number of arrivals in a single day was 1,185 (compared to 416 in 2020). Despite this increase, the UK’s small boat arrivals are a fraction of the number of migrants arriving in Europe, with more than 120,000 people coming to Europe via the Mediterranean by land and sea in 2021, according to data from the UNHCR.

Despite the comparatively small number of people, migration remained a national story for much of the year, often discussed in discriminatory and alarmist terms. Optimistic Brexit assurances about reducing migration have not materialised – and the daily drip feed of anti-migrant content in major newspapers such as the Daily Mail has contributed to a hardening of attitudes.

Unsurprisingly, immigration has also been a central issue for the British far right and supporters have been active in this area. It is also now attracting attention from far-right groups who had not seriously engaged with the issue before now. Far-right anger has been directed towards migrant accommodation, too, with a rising number of filmed visits to suspected migrant housing.

Several events during 2021, such as an attack by a failed asylum seeker in Liverpool or a planned resettlement scheme, have been seized on by the far right to serve their anti-migrant and dehumanising narratives. Social media content is regularly posted by anti-migrant “citizen journalists”, filming migrants arriving on boats or harassing hotel staff where they suspect migrants are being housed. Far-right groups have also dropped banners in certain locations, calling for an end to immigration and doing their best to stir up community tensions.

Dover remains one of the key areas for migrant arrivals and therefore one of the most popular destinations for anti-migrant activists. For several in the far right, filming the arrival of such migrants makes up the bulk of their online content. This is then shared widely on various messaging boards, accompanied by hundreds of angry and racist comments.

Interest and mobilisation across these groups surges after certain events. One such example was a demonstration in Dover on 29 May 2021, which received support from more extreme segments of the far right, including the British Nationalist Socialist Movement. Just 60 people attended the actual event, but the organisers declared it a success after they managed to bring the roads around the port area to a standstill for several hours.

The far right often justify their hatred of immigrants by citing attacks. These incidents serve as flashpoints that increase online far-right activity and self-reinforce their narrative about ‘violent foreign males’ supposedly ruining the United Kingdom.

When Emad Al Swealmeen blew himself up with a home-made bomb in a taxi, he was the ideal perpetrator for such mythological far-right narratives. An Iraqi-born failed asylum seeker who converted to Christianity, his attempted attack (which failed after he blew himself up inside a taxi) in Liverpool last November was quickly linked by the far right to the influx of people arriving in Dover. The fact the Al Swealmeen lied when trying to claim asylum confirmed every far-right suspicion. Within the scramble of misinformation post-attack, asylum seekers were all tarred with the same brush on far-right social media platforms.

Perhaps the best-known of the self-proclaimed ‘migrant hunters’ is Alan Leggett (aka Active Patriot). Leggett regularly demonises arriving migrants. He tried to capitalise on the botched Liverpool bombing by attempting to film the house of the suspected attacker – he was blocked by police – and also confronting journalists reporting on the issue. A video of him going on an anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim rant was widely shared across far-right and conspiratorial online spaces.

More generally in the far right, the linkage between migrants and terrorism has been framed in three ways. First, as a warning of how dangerous migrants arriving in small boats can be – homogenising a desperate community with the actions of an attacker. Second, as a criticism of the government for its failure to remove asylum seekers whose claims have been rejected (despite this government’s relentless efforts to create a more hostile environment for those seeking asylum). Third, as highlighting the perceived dishonesty of the BBC and other mainstream media outlets over their reporting of the attack – discrediting reputable news sources is a recurring tactic for the far right.

Failed asylum seekers are not the only targets for the far right. When Sir David Amess MP was stabbed to death by Ali Harbi Ali, a British man of Somali origin, Somalis in the UK were targeted by threats and abuse. Steve Laws, another ‘migrant hunter’ known for his filming of arriving migrant boats, was one of the many who “othered” the killer and likened him to an invader.

Laws ran (and lost) as a UKIP candidate in Amess’ former seat. Since then, he has continued to push associations between terrorism and asylum seekers – trying to whip up outrage that asylum seekers continue to arrive in the UK despite raised terror threat levels. He supports the ‘Great Replacement’ conspiracy, a white nationalist belief that states ethnic white populations are being demographically and culturally replaced with non-white, and specifically Arab and sub-Saharan Muslim populations, through mass migration and demographic changes.

General Islamophobia is also rife across Laws’ Telegram channel and he has repeatedly used degrading language such as “invaders” and “swarm” to describe migrants. He also helped organise an anti-migrant demonstration in Dover in May 2021 and is mostly known for his video content filming migrants arriving in Dover, which has been shared online by many far-right groups.

The fact that Sir David Amess’ murder was followed a day later by the anniversary of Samuel Patty’s death further inflamed the far right. Patty, a French schoolteacher, was stabbed and beheaded by a refugee from Chechnya in 2020 for having shown cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad in a class on freedom of speech. Many anti-migrant far-right figures used Patty’s death to claim why new migrants were dangerous.

More generally, though, the far right in the UK have exhibited simmering resentment towards the French. Anti-migrant activists have become adept at using ship-tracking software to trace French and British vessels engaged in policing and rescuing migrant boats. This has led to increased anger towards the French, who they claim are being given millions of pounds by the British government while escorting migrant boats into British waters.

Another clear source of anger for the far right has been the Afghan citizens’ resettlement scheme, which was designed to offer sanctuary for up to 20,000 “vulnerable” people after the fall of Kabul to the Taliban in 2021. The primary messaging from groups such as Britain First and For Britain has been the cost to British taxpayers. In doing so, they are reviving and refining similar attacks used during the Syria crisis, using Islamophobic narratives of a “Muslim takeover of Europe” and framing refugees as potential terrorists or sexual predators. For Britain focused on the unemployment migration would cause and criticised the Conservative government’s Operation Welcome that would supposedly “bring in tens of thousands of undocumented Afghans”. Meanwhile, the nazi group Patriotic Alternative has pushed a “Write to your MP” action for its followers, to express concern about the proposed resettlement of Afghan migrants in the UK.

Nigel Farage also unsurprisingly waded in to claim a failure by the Home Secretary, saying: “You may as well put a sign on the White Cliffs of Dover saying everybody welcome and you won’t be deported.” He used his platform on GB News (new TV network) to make alarmist claims about waves of Afghan refugees, and thousands of others making bogus claims to be Afghans, all descending on the UK.

Farage represents a midpoint between the mainstream and the far right. Migration has become one of his main talking points and on one occasion he hired a boat and sailed into The Channel to film migrant vessels. He received some pushback after unwisely criticising the RNLI (the charity which provides lifeboats and crews across the UK) for its work helping some of those vessels in distress. This became a national news story and, following a campaign by HOPE not hate and others, led to a great increase in donations to the organisation. However, within the far right it is worth noting that Farage’s claims are widely accepted and promoted, and expertly packaged to promote indignation and anger.

In addition to general anger against migration, there is a more focused opposition to the housing of migrants in hotel accommodation around the UK.

According to official statistics there are currently up to 16,000 asylum seekers in temporary accommodation, including hotels, hostels and disused military barracks across the UK, while they await longer-term housing. The overall number of people staying in asylum-related facilities has tripled in the past 10 years to 64,000. Anti-migrant activists have attempted to generate outrage by comparing the accommodation provided to “foreigners” with the situation of homeless British people, especially military veterans.

Tracking and analysis by HOPE not hate has found at least 125 hotel visits by anti-migrant figures in 2021 and this could even increase in 2022. It is important to note that while the official aim of these videos is to confront and harass migrants, less than 15% of the recorded visits in 2021 included a confrontation. The activists often just filmed hotel buildings while mouthing monologues, or sometimes attempted to enter and were stopped by security guards.

Amanda Smith, an anti-migrant activist going under the name “Yorkshire Rose”, is by far the most prolific YouTuber here. Her channel (with just under 2000 subscribers) mostly consists of videos where she films herself visiting hotels she suspects are housing asylum seekers, then harasses staff, security guards and anyone she suspects of being a migrant. In January 2021, she and Alan Leggett (“Active Patriot”) were arrested for causing alarm and distress during one such incident, and she claims they were banned from the area as part of their bail conditions.

A Britain First activist, James White, was also convicted of assaulting a security guard at a hotel housing asylum seekers. The incident occurred on 29 August 2020 and came during one of the many protests and hotel “invasions” carried out by Britain First. White was found guilty of assault in his absence in 2021, after failing to attend his trial.

Britain First has often used the issue of hotels in this context to promote its other divisive messages, for example around grooming scandals. Britain First supporters held a small protest in September last year at the Britannia Hotel in Standish near Wigan. They made allegations that male refugees at the hotel were sexually harassing schoolgirls, claims that police said were baseless. It is not the first time the far right has made such false claims. Stephen Yaxley-Lennon (aka Tommy Robinson), the former leader of the English Defence League, has also pushed out the issue. He posted a video on 10 September saying: “All that matters is our children’s safety,” which was viewed over 30,000 times.

Leggett has also pushed the ‘migrants are sexual predators’ narrative. He released a documentary in December 2021 about so-called “Muslim grooming gangs” (Steve Laws helped edit it), which he toured across seven northern towns. From the start of the tour in Rotherham to its end in Rochdale, there were few audiences for the film, which Leggett broadcast via a portable screen in public locations. However, his subsequent filming of his actions and of the screen on his Telegram channel were then widely shared in far-right circles.

Other content-creators regularly covering the migrant issue include Christopher Batt (aka Tyrant Finder UK) from the West Country and Chris Johnson whose videos are widely shared, including by Stephen Yaxley-Lennon.

Several of the anti-migrant activists have been taken to court over their actions in 2021, with mixed success. The largest case was brought against Steve Laws, Tracey Wiseman (aka XxTWxX), Alan Leggett and Nigel Marcham (aka Little Veteran) by Dover Harbour Board. The latter two signed an undertaking stating they would not intimidate asylum seekers or enter the docks without permission, under the penalty of jail time and a fine. Marcham, who was a key player in the anti-migrant scene in 2020, announced in December 2021 that he was tired of confrontations with Dover police and that he would now only be focusing on his real passion, which was helping homeless veterans.

Leggett on the other hand did not seem fazed by the ruling, while Steve Laws refused to sign the undertaking and his case will continue in 2022 (Laws has been to court several times in 2021 including being found not guilty of breaching the peace in January, and being found guilty for stealing and joyriding a dinghy that had originally been used by asylum seekers to cross The Channel – although he has appealed the latter and the case will resume in 2022.)

Most anti-migrant activists film themselves before and after court, giving monologues about their brave actions, as well as painting themselves as victims being persecuted for protecting their country. This is often accompanied by details of how supporters can donate to their cause.

The issue of cross-channel migration will likely continue to garner headlines and cause debate and discussion. However, it is vital that the hysterical and prejudiced voices of the far right are not legitimised or normalised in this delicate and difficult issue. When the mainstream media interviews an anti-migrant and far-right activist, for example, they should reveal his affiliations and should merely describe him as a “commentator” – as was the case for Steve Laws when he was interviewed by talkRadio last year.

Far-right citizen journalists repeatedly claim to be telling the “real truth”. In the age of alternative facts and the crumbling of political integrity, this rhetoric is seductive and increasingly dangerous. It must not become the new norm.

The violent far right is part of a complicated landscape, one in which increasing numbers of young people are being sent to prison, say Patrik Hermansson and Nick Lowles.

The threat of far-right terrorism remains high in the UK. There were 18 far right sympathisers convicted of terror-related offences in 2021, a 50% increase on the previous year. This comes as the number of referrals to the government’s Prevent counter-terrorism programme relating to far-right extremism exceeded those for Islamist radicalisation for the first time.

While there were no serious terrorist attacks carried out by far-right extremists last year, this probably owes more to early interventions by the authorities rather than a lack of seriousness and intent.

In what is now a clear police tactic, far-right activists are being arrested and networks disrupted at a far earlier stage than might have been the case in the past. With more and more far-right sympathisers being caught and convicted with possession of material useful for a terrorist act, Counter-Terrorism Police (CTU) clearly believe this early intervention prevents more serious plots developing.

The combination of the police and security services taking the far-right threat more seriously, this process of early intervention – combined with the growing threat itself – has seen 76 far-right extremists convicted under terrorism legislation since the beginning of 2017. This compares to just 15 in the previous five years.

The age of those being convicted is getting ever younger, too. The average age of those convicted since 2017 is just 28. There have also been 18 teenagers convicted during this period. In the 2012-2016 period, the average age was 31 and there were just two teenagers.

Several other patterns can be seen among the cases over the last year. Many convictions relate to the Telegram chat app, which has emerged as an important organising platform for the terror-advocating far right in recent years. While many arrests relate to relatively minor terror-related crimes that might not have been prosecuted under terror legislation a decade ago, a growing focus on improvised weaponry is a worrying and potentially deadly trend.

National Action (NA), the group proscribed at the end of 2016, still makes itself felt. Among those convicted last year was NA co-founder, Ben Raymond, who was given an eight-year sentence in December. He became the 17th person convicted of membership of the group, whose former spokesperson once planned to murder an MP (before being exposed by HOPE not hate and sentenced to life in prison). Proscription of the far-right terror group continues to lead to arrests and convictions years after its breakup.

Benjamin Hannam, a Metropolitan Police officer, was found guilty for membership in NA in April. Andrew Dymock, who led the NA splinter group Sonnenkrieg Division, was also convicted on 15 offences and jailed for seven years in July.

Telegram continues to be at the centre of the terror-advocating far right. The platform’s extremely lax moderation practices, relative anonymity, combined with social media-like features, have made it attractive across the far right. And over the last years, it has been used extensively by far-right terror groups.

There have been multiple arrests and convictions in the last year relating to Telegram. Three members of The British Hand, a terror-advocating group that sprung up on the platform in the summer of 2020 (and was exposed by HOPE not hate in the same autumn) were convicted in 2021. Another case is Ben John, who used the platform to access terror material.

Michael Nugent, 38, was also convicted in 2021 after being caught sharing explosives and firearms manuals in extreme-right online chat groups on Telegram.

The Feuerkrieg Division was the first nazi group originating on Telegram to be proscribed in the UK in 2020, and in February this year the first prosecution on the basis of membership in the organisation took place.

As long as Telegram fails to decisively take action against fascist groups on its platform, it will likely remain the app of choice for the movement. Because of its social media features and good support for video, it functions as an outreach and recruitment platform as well as an organising and private communication platform for many extremists.

The platform has dramatically lowered the barrier of entry to fascist and terror-advocating groups, too. The multitude of chatrooms focused on fascism and normalisation of extreme language, to a large part driven by a perceived sense that it was a secure platform has inevitably led many to cross the line into activities that can be prosecuted under terror legislation. Naivety, combined with rapid radicalisation, explains some of the arrests of young, far-right supporters using the platform. Combined with an increasing focus on Telegram and far-right terrorism more broadly, this has driven up the number of arrests.

This does not mean that these groups do not present a real threat. They provide spaces for radicalisation, and the groups help motivate individuals to take action. Matthew Cronjager is a clear example in point. As a member of The British Hand, the 18-year-old took part in a chat group that traded in extreme and violent anti-Muslim rhetoric. He later started his own fascist Telegram group and was eventually convicted for plotting to kill an Asian classmate.

The movement has increasingly taken notice and begun to look for alternatives to Telegram. However, many move back onto Telegram because of its user friendliness and the existing network that is active on the platform. Instead, many groups have begun to make background checks harsher and more extensive in an attempt to stave off both police and anti-fascist infiltrators.

Attempts at constructing weapons rather than acquiring industrial-made counterparts is a growing and potentially deadly trend. Matthew Cronjager had plotted to shoot a classmate using a 3D printed weapon. Additionally, an ongoing trial of three men from West Yorkshire who belonged to a Telegram group called “Oaken Hearth”, glorified nazi terrorists and had begun 3D printing parts of a gun. The group also experimented with other kinds of homemade weapons, including producing napalm.

Some forms of extreme violence can be difficult to categorise. Danyal Hussein was convicted last October for the murder of two women in Wembley the year previously. Hussein did not support the far right, but his murder was motivated by satanism and misogyny. The teenage murderer had signed a contract in blood with “the mighty king Lucifuge Rofocale”, in exchange for sacrificing “only women” every six months.

The double murder was at least partially inspired by an American satanist and, at one point, Temple ov Blood supporter, Matthew Lawrence (aka E.A. Koetting).

The leader of the Temple ov Blood, an American chapter of the nazi-occult group, the Order of Nine Angles, was in direct contact with Andrew Dymock, the British leader of the Sonnenkreig Division, who was also convicted last year.

Improvised weapons have attracted attention from violent far-right groups in the UK and Europe in the last years because access to industrial weapons is challenging. The most notable example is Stephan Balliet, who attacked a synagogue and a Turkish restaurant and killed two people in Halle, Germany in 2019. The attacker explicitly aimed to “Prove the viability of improvised weapons”, according to a letter released before his attack.

While construction of functional weapons remains relatively difficult, even if one has access to a 3D printer, it still requires knowledge of materials and how to assemble the pieces and access to, or skills to make, ammunition. However, instruction manuals – and in the case of 3D printing schematics compatible with commercial 3D printers – for building firearms as well as explosives are being constantly improved and becoming easier to access than ever before.

Telegram, again, has become an important platform for distributing these manuals. The platform has channels explicitly focused on distributing weapons manuals and schematic files for 3D printers. In the case of printing, these channels are often not explicitly far-right, but rather run by libertarian-leaning US organisations that hold gun ownership as an essential right. However, on this side of the Atlantic, they have come to be shared extensively by the fascist far right.

Ben Styles, currently on trial related to building a machine gun in his garage in Leamington Spa, allegedly had manuals to convert blank bullets (which can be bought legally) into functioning live ammunition. Styles was also active on Telegram and had allegedly sent messages in support of the mass shooting in Christchurch, New Zealand and written: “I hope the holocaust is real next time”.

Separately, older weapons manuals are circulating that describe how to build weapons rather than 3D print them. An especially popular variant is the “Luty”, a submachine gun that can be constructed by easily accessible components. It was designed by English anti-gun control activist Philip Luty in the 1990s. Balliet, the shooter in Halle in 2019, used a Luty.

Easy access, combined with ever-increasing violent rhetoric in far-right Telegram groups, has helped spread the idea of improvised weapons in the far right. It is important to understand that these are not always shared with the explicit intent of the receiver using them, but rather as a way to demonstrate extremeness and elicit a reaction from others in the group. However, the effect is that these manuals are more and more readily available across Telegram, also in chats that are not explicitly terror advocating.