HOPE not hate uses cookies to collect information and give you a more personalised experience on our site. You can find more information in our privacy policy. To agree to this, please click accept.

Download the full report, including exclusive polling and analysis here.

By Rosie Carter and Nick Lowles

Fifty years on from the Rivers of Blood speech, Enoch Powell’s dire predictions of societal collapse have not materialised. But anxieties around immigration and integration continue to cause concern for many.

According to an exclusive YouGov poll of over 5,000 people commissioned by HOPE not hate (building on previous Fear and HOPE polls commissioned by HOPE not hate since 2011+), the British public remains pessimistic about the state of multiculturalism and integration, and fears it will get worse.

While there is a gulf between people’s negative perceptions and the more cordial reality, multiculturalism has been an uneven success, leaving some areas of Britain more integrated than others.

There have been huge advances in race relations, thanks to governmental and non-governmental action and the growth of closer connections between different communities. But many challenges remain across, and between, these communities, and also in some specific areas of the country.

With anxiety about British Muslims and Islam in particular replacing immigration as the main area of concern 50 years since Powell’s speech, challenging anti-Muslim prejudice and creating a more positive narrative around British Muslims will be a central to the continuing advancement of race relations in the UK.

Powell’s dire predictions of societal breakdown haven’t materialised but people remain pessimistic about the state of multiculturalism and integration, and fear it will get worse.

Exclusive YouGov polling of 5,200 people for HOPE not hate has found:

However, there appears to be a gulf between perception and reality. The reality is that multiculturalism has been an uneven success, leaving some areas of Britain more integrated than others.

There have been huge advances in race relations, from governmental and non-governmental action through to closer connections between different communities. However, many challenges remain across, and between communities, and in some specific areas of the country.

As when Powell spoke, a huge amount of work was needed to provide alternative messages of hope, and real action from government and communities to stop Powell’s vision from becoming reality, we need action today to stop a slip towards hardening attitudes and to rebuild public trust. Powell’s speech prompted action, the anniversary must do the same.

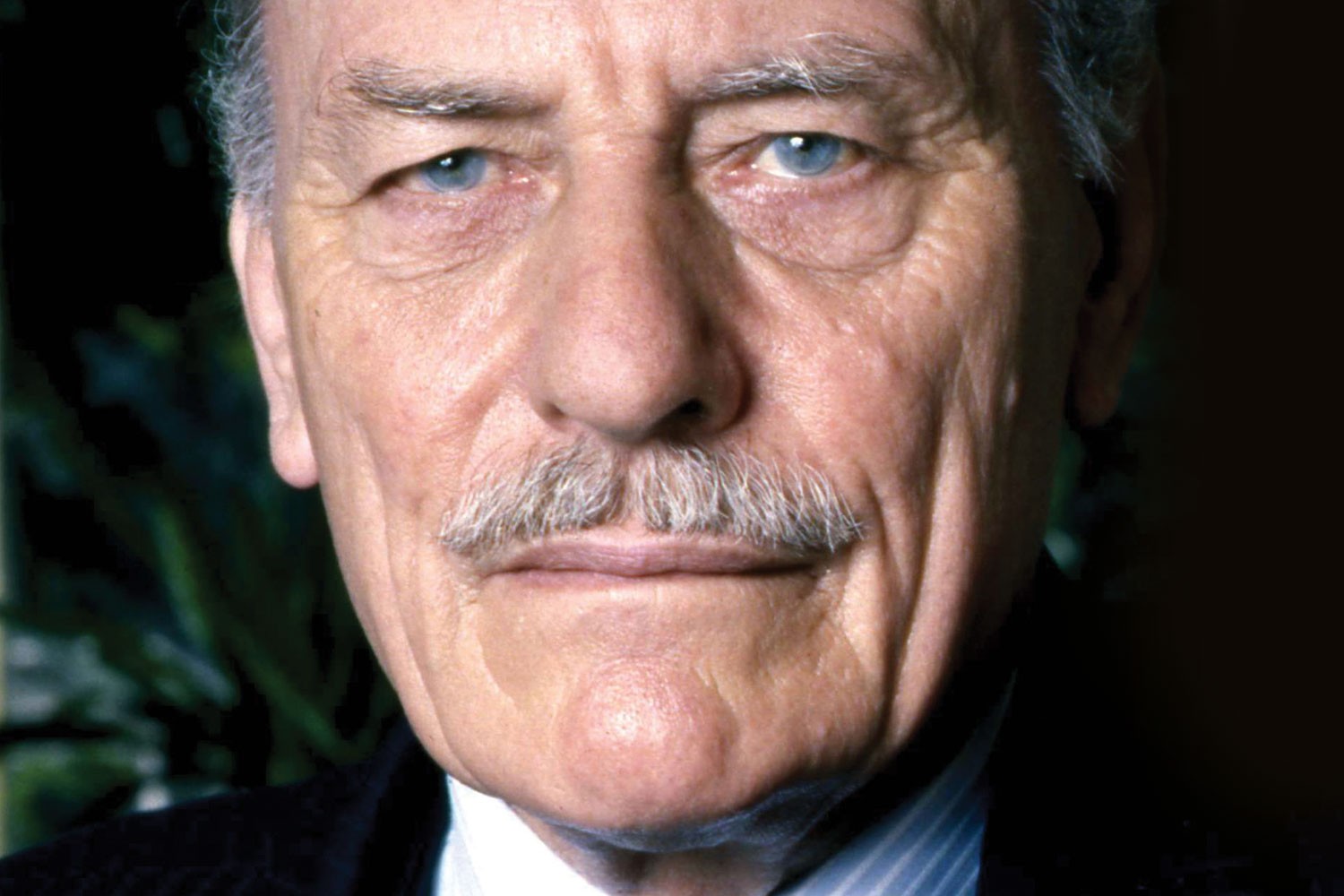

On Saturday 20 April 1968, at the Midland Hotel in Birmingham, Conservative shadow defence spokesman and MP for Wolverhampton South West, Enoch Powell, made arguably the most infamous speech in modern British political history.

Delivered to a Conservative Association meeting attended by 85 people, the speech was startlingly racist and demagogic in tone, coupling prejudices about non-whites with an apocalyptic vision of racial conflict and calls for the repatriation of immigrants.

Powell’s speech, which he neglected to clear with his party, was carefully planned and intended to provoke. Prior to the delivery of the speech he cryptically told the editor of a local paper: “You know how a rocket goes up into the air, explodes into lots of stars and then falls down to the ground? Well, this speech is going to go up like a rocket, and when it gets up to the top, the stars are going to stay up.”

During the speech itself, he claimed that he could “already hear the chorus of execration. How dare I say such a horrible thing?”

Despite the small immediate audience, sections of the Tory media ensured that the fallout of the speech was felt all over the country, and, as demonstrated by recent rows over a plan to commemorate Powell with a blue plaque in Wolverhampton, continues to cause division today.

Powell delivered his speech just days before Labour’s Race Relations Bill of 1968 – which was to outlaw discrimination in housing, employment or public services on the grounds of ethnicity or national origins – was due to have its second reading.

The speech was also made against the backdrop of political jostling and animosity between Conservative leader Edward Heath and Powell, who, according to his biographer Simon Heffer, was determined not to be sidelined.

The ensuing scandal catapulted Powell into the national headlines, MP Angus Maude describing it as “a sensation unparalleled in modern British political history”.

The Times, which supported Heath, declared it “an evil speech”, writing “this is the first time that a serious British politician has appealed to racial hatred in this direct way in our postwar history”. The Sunday Times damned him for “spouting fantasies of racial purity.”

Powell attributed some of the speech’s most inflammatory passages to his constituents and the press scoured Wolverhampton for an old aged pensioner – purportedly now the only remaining white resident of her street – and who was being harassed by her new “negro” neighbours, allegedly suffering “excreta” being pushed through her letter box and being stalked by “charming, wide-grinning piccaninnies.”

The press could not locate such a woman, leading to pointed questions over her actual existence.

Leading Conservatives Iain Macleod, Edward Boyle, Quintin Hogg and Robert Carr all threatened to walk out of the Shadow Cabinet unless Powell was sacked. Heath himself lashed the speech as “racialist in tone and liable to exacerbate racial tensions” and sacked Powell, with unanimous support, from the shadow cabinet.

Powell banished to the backbenches for the rest of his political career, left the Tories in acrimonious fashion to become an Ulster Unionist MP in 1974.

The “Rivers of Blood” diatribe instantaneously transformed Powell into a lightning rod for latent anti-immigrant sentiment. Both the Daily Express and News of the World supported him and, on 23 April, a small minority of London dockers struck to protest at Powell’s “victimisation”, marching from the East End to Westminster, some reportedly with signs, handed to them by fascists, saying “Back Britain, not Black Britain”.

Heath was reportedly forced to enter through a back entrance in order to speak in Dudley Town Hall seven days after Powell’s speech due to a crowd of about1,000 people singing racist songs and chanting “Heath out, Enoch in”.

The speech also solidified Powell’s status as a cult hero within the right-wing of the Conservative party. Heffer writes that Powell was supported by MPs Duncan Sandys, Gerald Nabarro and Teddy Taylor. The imperialist, racist Conservative Monday Club handed representatives badges promoting as Powell its “Man of the Year” at the party conference in Blackpool.

In 1970, Monday Club member Beryl “Bee” Carthew established the newsletter Powellight. By 1971, the Monday Club claimed over 10,000 members and 35 MPs.

Powell’s speech also buoyed the burgeoning National Front (NF), formed in 1967. Powell’s sacking led some staunch Powellites to defect to the NF. John O’Brien, for example, initially attempted to organise a “Powell for Premier” movement within the Tory party before drifting into the NF and briefly becoming its leader in the early 1970s. Carthew of Powellight would also join the NF and, later, play a prominent role in the far right group, the London Swinton Circle.

To a degree Powell also inspired to John Tyndall, who led the NF through much of the 1970s under a racist and anti-immigrant message that added to his hardcore nazism. Tyndall, who would later found the British National Party (BNP), invited Powell to represent the party as a candidate in Wolverhampton South West. Powell declined.

As Jonathan Rutherford writes in Forever England: Reflections on Masculinity and Empire, the Tories won an unexpected victory in the 1970 General Election and Powell was interpreted by some contemporaries to have played a vital role in changing the landscape of debate and drawing in new voters.

Despite publically abhorring Powell’s words and the mounting thuggery of the NF, the Conservatives promised “no further large-scale permanent immigration” in the election and in 1971 introduced the Immigration Act, restricting immigration into the UK.

Margaret Thatcher, elected in 1979, consolidated racially discriminatory immigration laws in the British Nationality Act of 1981.

The phrase “Rivers of Blood” soon became synonymous with whipping up fear and tensions around immigration, and invoking the speech came to be regarded as beyond the pale in mainstream politics. Nonetheless, the speech helped change the landscape of British politics by proving the power of the issue of race.

Powell claimed that “people are disposed to mistake predicting troubles for causing troubles.” However, numerous accounts attest to the fear and strife that “Rivers of Blood” provoked in communities housing immigrants.

Ten days after the speech, The Times reported a slashing attack on attendees of an Afro-Caribbean christening party in Wolverhampton. One of the victims, Wade Crooks, told the press that the young white assailants were chanting “Powell, Powell”. “I have been here since 1955”, he said, “and nothing like this has happened before. I am shattered.”

The comedian Sanjeev Bhaskar told the BBC that at the end of the 1960s Powell was a “frightening figure” for his family, who kept suitcases readily packed in case they were forced out.

Britain’s first mixed-race cabinet minister, Paul Boateng has spoken of being spat on and abused in the streets in the wake of “Rivers of Blood”. There are many other such examples.

Dr Camilla Schofield reports in, Enoch Powell and the Making of Postcolonial Britain, that in the wake of Powell’s speech violence against Britain’s ethnic minorities took on “a clearer political meaning.”

Members of the West Midlands Caribbean Association began referring to the time prior to 20 April 1968 as B.E: “before Enoch”.

Such attacks were not absorbed passively, however. As an explicit reaction, more than 50 Caribbean, Pakistani and Indian labour organisations formed the Black People’s Alliance, leading to 8,000 people taking part in the “March for Dignity” in 1969 against racism and in opposition to the 1968 Commonwealth Immigrants Act.

This was the largest demonstration against racism Britain had yet seen. As Schofield relates, “Rivers of Blood” helped to politicise the issue of racism and racial inequality and opposition to it sowed the seeds for future anti-racism and anti-fascism campaigns.

Powell remains a hero on the extreme margins and, thanks to the internet, now claims an international following. For example, it is not uncommon to see his image on alt-right propaganda, and the open American fascist Mike Peinovich (aka Mike Enoch), the founder of influential alt-right hub The Right Stuff and co-host of the noxious antisemitic podcast The Daily Shoah, chose his pseudonym in reference to Powell.

Worryingly, Powell is slowly being rehabilitated closer to the mainstream. As The Economist has pointed out, Brexit has seen a revival of his politics that were rooted in anti-immigration and anti-EU sentiment.

Our Fear and Hope 2017 report revealed that while an increasing number of people are tolerant and open to immigration and multiculturalism – in part due to a belief that Brexit will “solve the problem” – society is deeply polarised, and 23% of society remains bitterly opposed to immigration and multiculturalism.

Powell is now being openly embraced by politicians wishing to exploit this sizable pool of antipathy. Former UKIP leader Nigel Farage is a well-known admirer of Powell.

Farage asked Powell for his support in a by-election in 1994 and, while not endorsing Powell’s tone, claimed in 2008 that his “principles remain good and true” and that “had we listened to him, we would have much better race relations now than we have got.”

More recently, Farage’s support for these principles has come through in his involvement with Leave.EU, the unofficial Brexit campaign headed by Farage and former UKIP moneyman Arron Banks.

The campaign has relentlessly linked the European Union to immigration and the latter to social decline and violence. Farage is not an anomaly within UKIP in this respect. In 2015, UKIP MEP Bill Etheridge gave a speech in Dudley, claiming that “the creed of multiculturalism is in fact a creed of surrender and it will lead to rivers of blood.”

Whilst Powell’s almost messianic visions of race war have failed to materialise, the phrase “Enoch was right” has long been a common slogan in far right politics.

Worse, recent radical Islamist attacks in Europe now reliably prompt claims that “Powell was right” even in mainstream publications like The Telegraph and the writer and journalist Douglas Murray has claimed that “portions” of the speech “now seem almost understated” in his 2017 bestseller The Strange Death of Europe.

50 years on, the spectre of “Rivers of Blood” continues to cast a dark and sinister shadow over British politics.

Our poll paints a depressing picture of how people feel about multiculturalism and integration: 40% of people felt Enoch Powell had been right to predict rivers of blood, while 41% thought he had been wrong.

But this isn’t a popularity contest: there is fact and fiction, and the reality is that Powell was wrong. The views he espoused in his speech weren’t just abhorrent, they have been discredited by the passage of time.

“In this country in 15 or 20 years’ time the black man will have the whip hand over the white man.”

This has not happened.

Powell’s racist scaremongering hasn’t come to pass. In fact the opposite is true. Race inequality remains entrenched and far-reaching across many areas of society. Only 36 of the UK’s 1,000 most powerful people are from Black and minority groups. That’s just 3% of the UK’s top political, financial, judicial, cultural and security figures, disproportionate to 14% of the working age population from a BAME background.

The Government’s own racial disparity audit finds racial inequality across a range of socioeconomic measures. Unemployment rates for Black, Asian and minority ethnic people almost twice that of white British adults. Over half of Asian and black households fall into the lowest two income quintiles and white British people are still most likely to be home owners. Black Caribbean pupils are permanently excluded from school at three times the rate of white British pupils, and Black British people are eight times more likely to be stopped and searched by police than white people.

“In 15 or 20 years, on present trends, there will be in this country three and a half million Commonwealth immigrants and their descendants…. There is no comparable official figure for the year 2000, but it must be in the region of five to seven million, approximately one-tenth of the whole population, and approaching that of Greater London. Of course, it will not be evenly distributed from Margate to Aberystwyth and from Penzance to Aberdeen. Whole areas, towns and parts of towns across England will be occupied by sections of the immigrant and immigrant-descended population.”

Powell sought to use these numbers to claim an impending doom. The 1981 census estimated just over 2.2 million people for whom the head of the household was from the New Commonwealth, the migrants and their descendants Powell was most fearful of. It also records 1.3 million migrants from the rest of the world, including Old Commonwealth countries. The 2001 census records the population of all minority ethnic groups in the UK to be 4,635,296, around 8% of the population, and short of Powell’s estimations. The numbers were off, but more importantly the idea that immigration would tear Britain apart is so wrong that it undermines Powell’s central argument.

Powell looks to the U.S. as an example of Britain’s future, and predicts consequences of changes to the 1965 Race Relations Act which made it illegal to refuse housing, employment or public services to people because of their ethnic background, and created the Community Relations Commission (CRC) to promote ‘harmonious community relations’.

“They found their wives unable to obtain hospital beds in childbirth, their children unable to obtain school places, their homes and neighbourhoods changed beyond recognition, their plans and prospects for the future defeated; at work they found that employers hesitated to apply to the immigrant worker the standards of discipline and competence required of the native-born worker; they began to hear, as time went by, more and more voices which told them that they were now the unwanted.”

Concerns around pressures placed on housing, public services and the NHS, and about wage suppression and the undercutting of working conditions as a result of immigration remain incredibly salient. But how do these concerns stand up to evidence?

Any population growth demands a greater supply public services and infrastructure, and immigration does add to population growth. But the reality is complex, as most migrants are also tax payers and contribute towards these services.

Healthcare is now a more salient public issue than immigration, the NHS is struggling to cope with record demand and social care services are stretched to the limit. The number of people waiting more than four hours for treatment in A&E has risen by nearly 600%. But there is no correlation between the proportion of immigrants in an area and the performance of local A&E departments. In 2014, FullFact estimated that migration from the EU added £160 million in additional costs for the NHS across the UK, while the Kings Trust estimate that ‘health tourism’ costs the UK between 60-80 million pounds a year. But this is less than 10% of the annual NHS budget of £113 billion, and does not account for migrants’ contribution through taxation, or the NHS surcharge paid by migrants from non-EU countries. Nor does it account for the importance of migrant labour in running the NHS. Further, immigrants are less likely than people born in the UK to access services, as they tend to be younger.

It’s also hard to determine the impact of immigration on school places. Between 2011-2011 fertility rates increased alongside immigration, as non-UK born women have a higher fertility rate than those born in the UK. More children means more school places, but creating school places requires public funding, which migrants add to. 2016 estimates from HMRC but the tax and national insurance contribution of EEA nationals at £3.11 billion. At the same time, education policies have been slow to react, and since 2001, Governments have cut back on empty school places in primary schools. Further, the introduction of free schools and academies means local authorities can’t build new schools without first seeking proposals for a free school and don’t have the authority to tell academies to expand.

Research suggests that immigration has a small impact on average wages of existing workers, but that this is contingent on skills of workers and the characteristics of local economies. Low-wage workers are most likely to be hit by any impact, but these impacts are also most likely to be felt by resident workers who are also migrants. Evidence on wages is complex, and highly determined by economic changes, and declines in the wages and employment of UK-born workers in the short run can be offset by rising wages and employment in the long run.

“Now we are seeing the growth of positive forces acting against integration, of vested interests in the preservation and sharpening of racial and religious differences, with a view to the exercise of actual domination, first over fellow-immigrants and then over the rest of the population. As I look ahead, I am filled with foreboding; like the Roman, I seem to see “the River Tiber foaming with much blood.”

Over 80% of people feel well integrated into their communities. Our research finds the majority of people have close friends of a different ethnic background to their own, and a quarter of Londoners have been in a relationship with someone of a different ethnicity to themselves, significant for any Western European country, and the vast majority of people (76%) see their community as peaceful and friendly.Race relations have not always been easy, but rhetoric like Powell’s only stirs up tensions, creates new challenges, and adds fuel to the fire. The vast majority of people will not have been as familiar as Powell with Greek mythology, and will more likely read an association of diversity with violence, of multiculturalism’s failure as social breakdown. Of course, this has not happened. But there is much to be done to improve both perceptions and realities of community relations in an increasingly diverse Britain.

Footnotes

1The Guardian, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/inequality/2017/sep/24/revealed-britains-most-powerful-elite-is-97-white

2https://www.ipsos.com/ipsos-mori/en-uk/important-issues-facing-britain

3https://www.channel4.com/news/factcheck/the-number-of-people-waiting-over-four-hours-in-ae

4https://www.channel4.com/news/factcheck/high-immigration-nhs-crisis

5https://fullfact.org/europe/eu-immigration-and-pressure-nhs

6https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21389062

7https://fullfact.org/immigration/immigration-and-jobs-labour-market-effects-immigration

8Ethnicity Facts and Figures, 2017, https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/

9Fear and HOPE 2017

Powell’s dark and vicious predictions have failed to materialise, but there is a widespread perception that integration is failing and, more worryingly, people are also pessimistic about what the future holds. That’s the findings of an extensive poll carried out by YouGov for HOPE not hate.

On the surface, the results appear quite depressing. While 43% of our poll feel that Britain is a successful multicultural society where people from different backgrounds generally get along well together, 41% believe that Britain’s multicultural society isn’t working and different communities generally live separate lives. Three times as many people think that relationships between different communities within the UK will get worse over the next few years, with just 14% of people believing things will get better.

An astonishing 40% of people felt that Enoch Powell’s dire predictions of social breakdown and violence in his Rivers of Blood speech proved accurate, with just 41% of people believing that he was wrong. Clearly Powell’s dire predictions of societal breakdown have not materialised, nor has his claim that “the black man” would have the “whip hand” over indigenous Britons. In fact, the opposite has continued to happen, with the Government’s own Race Disparity Audit finding last year non-whites continuing to be discriminated against in the work place while unemployment is higher in non-white communities.

Race relations have advanced considerably since Powell’s speech. Britain is, despite its obvious problems, a more successful multicultural society than most other countries in Europe. Racial discrimination is outlawed and less acceptable than it once was. Attitudes towards immigration have improved dramatically in the last few years and Britain has culturally, economically and politically absorbed new cultures. There is still a lot more to do, but Britain is in a much better place than in was in 1968.

If race relations in Britain has improved since Powell’s days, then why the pessimism in our poll? There is clearly a large distinction between how people view the community around them and how they view society at large. Data from the community life survey shows that 81% of people feel well integrated into their community. And while most people’s community is made up of people who are like them, our poll shows most people have close friends from different ethnic background to themselves and almost a third of people say that they or a family member has been in a relationship with someone of a different ethnicity to themselves.

It is also clear that people’s views about society at large is heavily shaped by what they see and read on the television, in the newspapers and on the internet. The narrative around immigration and cohesion generally, and Muslims and Islam more specifically, is overwhelmingly negative and so it is hardly surprising that the view on integration in Britain is so poor. That is not to say that there are not many real issues facing us today. Our poll shows how the suspicion and fear of British Muslims and Islam more generally has replaced immigration as the key issue of concern for many Britons. 37% of all respondents see Islam as a threat to the British way of life compared to 33% who see the Muslim faith and the British way of life as compatible and last year’s terrorist attacks greatly increased suspicion towards British Muslims. Last July 42% of people said that their opinion of Muslims in Britain had worsened because of the attacks. Asked the same question in this poll, a fifth of respondents still hold this view.

A link between Islamic extremism and the failure of integration in Britain is drawn by a high proportion of the British public.

While Britain is a more integrated society than many of us initially think, there is no disguising the fact that a significant problems exist and must be tackled, especially those rooted in economic problems and cultural anxieties. As our report says, multiculturalism has been an uneven success, leaving some areas of Britain more integrated than others.

Unfortunately much of the debate about integration is polarised in Britain today, between those on the Right who believe that multiculturalism has failed and Islam is incompatible with the West and some on the Left who dismiss any criticism of multiculturalism and anxieties over cultural differences.

Building stronger, more integrated communities is one of the big challenges of our times. Most people do want Britain’s communities to live together peacefully and cohesively but prejudice and discrimination still exists, there is still not enough interaction between communities and the on-going activities of Islamist and far right extremism will continue to test our resilience in the years to come. Likewise, we must not be afraid to deal more robustly and consistently with difficult communal issues when they arise, because failing to address these only plays into the hands of the Right. With Britain’s rapidly changing demographics (with predictions that Britain’s BAME communities will make up 36% of the population by 2050), building stronger and more integrated communities must be a priority for us all.

Understanding where we are now is an essential to improving integration in the future. Just as Powell’s Rivers of Blood speech galvanised people into action, so let us hope that the 50th anniversary of his speech does the same.

Fifty years ago, Enoch Powell’s blistering speech about race in Britain ignited a touch paper that fanned the flames around the immigration policies of successive governments. Powell claimed that Britain was building its own funeral pyre, with “homes and neighbourhoods changed beyond recognition” and minorities demanding special treatment.

Powell was no fringe politician. At the time of the speech, he had challenged for leadership of the Conservative Party and had served as a Minister for Housing. A Cambridge scholar, known for his intellect and for his military service in World War 2, he wanted to serve as Viceroy for India and was a staunch imperialist. His eloquent anti-immigrant nationalism is echoed in the words of populist far-right candidates across Europe today.

Powell’s infamous speech came just after Martin Luther King’s assassination, as race tensions boiled over in the USA, and just as Britain debated the Race Relations Act 1968, which sought to end discrimination on the grounds of ethnicity or national origins. He was convinced this would lead the country to racial violence where (he claimed a constituent had told him) “the black man has the whip hand”.

The speech got Powell fired from high-level politics, with several senior members of the Conservative Party threatening to quit if he stayed on. But the echo of his words has been felt ever since, as immigration continues to be high up the media agenda and national debate, and apprehension grows around multiculturalism and integration, as covered by our new YouGov poll.

Wolverhampton, where Powell was an MP for a quarter of a century, was named the fifth worst city in the world by the Lonely Planet guide in 2009 and Queen Victoria is said to have closed her carriage curtains when travelling through the region – one of the most industrialised areas of Britain during the 19th century – as she was so offended by the sight of the landscape.

“Unemployment levels have been high, especially since the recession and the closure of a lot of heavy industry and the Black Country dialect can be a source of mockery. People have had to fight harder to get to where they are and as a result have thrived and become brilliant role models for the children,” says Lisa Harrison, a local artist and community organiser. “When you live in Wolverhampton, you’re aware of Powell in a way you perhaps might not be if you lived elsewhere – it keeps coming into one’s consciousness.”

Wolverhampton today has a population of 250,000 and is known for its high number of black and minority ethnic communities. Schools have had to adapt and adjust to differences.

The West Park Primary School became the first school of sanctuary in Wolverhampton, as part of a movement to build a culture of welcome and hospitality within the community, especially for refugees and asylum seekers. The school has also created a parent ambassador scheme to help arriving families settle.

Harrison has been working with West Park Primary School for over 10 years. The school has had to battle a specific aspect of Powell’s legacy: journalists from around the world descended upon the school after Powell’s reference to a constituent’s claim that his child was the only white pupil in her class at a school in Wolverhampton.

Last year, Harrison began a history project, ‘West Park Welcomes the World’, based on post-World War 2 history with a focus on Enoch Powell. Through it she invited school alumni who were students when Powell gave his speech, as well as academics and other leaders in the community.

Both students and parents got involved in creating a play that focused on the nature of community, and how resilient it has had to become after the ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech.

Harrison says the impact of the project on the children is incredible.

“The children are really finding their voice and now understand the significance of their school’s story. They feel responsible as citizens to demonstrate to the rest of the world that yes diverse communities can live harmoniously with each other – that there are no divisions between children who speak different languages and come from different places,” she says. “They’ll now say things like Enoch Powell was wrong.”

The project has had a ripple effect in the community and the play is being performed again this month during a conference reflecting Powell’s legacy. Incidentally, the play will be performed at the Heritage Centre, which used to be the Conservative club Powell frequented.

When HOPE not hate held a forum on immigration in Wolverhampton, participants felt attitudes differed significantly across generations when it came to diversity.

One person said it was “an age thing” and that “you would find a higher percentage of older people are more racist and against migration than you would younger people – and that’s because of schools”. They added: “Like in primary school there was only one Indian girl in my class, now, well when I was in high school there were twenty, thirty – it’s more equal, and now it’s getting better.”

Another participant said: “I think if you scratch the surface in some areas here, you will find racism, definitely. On the whole most people get on, but if you go to certain areas, and scratch the surface it will be there.”

Dr Shirin Hirsch, who is conducting a major research project at the University of Wolverhampton into the impact of Powell’s speech on local community relations, told the Voice Online:

“Powell’s speech is remembered by a whole range of different voices, but particularly for Black and Asian immigrant communities who had been targeted in the speech, the impact was felt strongly. We are interested in remembering the ignored, local stories within Wolverhampton and discussing new forms of racism but also anti-racist politics which intensified following the speech.”

Since Powell’s speech, some of yesteryears language is no longer acceptable, particularly the sort of commonly-used racial epithets.

However, this has morphed more broadly into fears about Muslims, for example, and doom-and-gloom worries about the supposed failure of multiculturalism in Britain. A YouGov poll of 5,200 people commissioned by HOPE not hate, found that 43% predicted relationships between different UK communities will deteriorate over the next few years compared to 14% who feel things will improve.

Yet when questioned about their own circumstances and their immediate community (rather than distant areas), people were far less pessimistic.

Pakistan-born journalist Sarfraz Manzoor says that his father would use Powell’s reputation to warn him against integrating too much with British people. “Powell’s name was regularly cited whenever my father wanted to remind me how easily Britain could turn against us.”

Whether it is former prime minister Gordon Brown speaking about ‘British jobs for British workers’, the former head of UKIP Nigel Farage blaming multiculturalism for the London terror attacks, Telegraph columnist Simon Heffer writing that the Paris attacks had proven Powell right, or the Archbishop of Canterbury claiming incompatibility between Islamic rules and British laws, Powell’s ideas are now part of the general political debate. The words that shocked British politicians in 1968 are now commonplace as Powell’s beliefs have become more mainstream and have some laud him as a ‘visionary’.

Harrison however believes that in Wolverhampton, Powell pushed the community to become more resilient and build stronger links between each other. She says schools could have a major role in developing an integrated society if it remains “outwards-looking” as they have “much to contribute” to the community.

“It gets a bad press – it’s never going to be at the top of people’s places to live but it’s nowhere near as bad as people think it is,” says Keith Whitwell, an Australian artist who’s been living in Luton for the part 30 years.

Luton is a working-class town with a population of 216,000, a major airport and an unfortunate tendency to feature in extremism-related news.

A former resident was part of an Islamist fertiliser bomb gang that planned to blow up a shopping centre, Stephen Lennon, former head of the English Defence League (EDL) was born there and the so-called 7/7 bombers who killed 52 people on London’s transport routes in 2005 took the train to London from Luton on the day of the attacks.

Nestled between more affluent towns, Luton struggles with drugs and gentrification. Millennial Londoners are increasingly picking Luton to settle in as property prices in the capital drive them out. But for more than a decade, Luton’s reputation has been linked to extremism instead, with countless journalists focussing on the town through the lens of failed integration.

Walking around Luton and asking about its reputation, people were quick to say it didn’t reflect what the town is actually like. “If Tommy Robinson [Stephen Lennon] wasn’t born here and the 7/7 bombers hadn’t travelled through here, we’d just be another British town dealing with the same issues every town faces,” one Lutonian told me on the street.

Fatima Rajina, a British Bengali Muslim, is both a school teacher in Luton and a teaching fellow at SOAS University in London. She points to the train station as she shows me around the town, “The 7/7 bombers walked through this bit here and that image was everywhere on the news. I was in sixth form. I remember just having finished my AS levels, and my friends and I, we just knew shit was going to kick off.”

Fatima’s grandparents moved to Luton in the 1960s, her grandfather working in a Vauxhall car factory before most of them closed in 2002. She, like many Lutonians, is frustrated by the portrayal of the town in the news and documentaries such as BBC 3’s “My hometown fanatics” which focused on the two extremes: the EDL and Al Muhajiroon, an IS and Al Qaeda supporting group.

“The Bury Park mosque is where my uncles pray and they were the ones who kicked out Al Muhajiroon, telling them not to ever turn up there with their leaflets again – local people have fought these people from the streets and it’s very much our community that is tackling this,” she says. “But then as a schoolteacher, I hear young people saying Luton is a “shithole” and I’m frustrated because they themselves have internalised what people have said about their town.”

One woman said she had a daughter working in London who always gets a mixture of grimaces and pitying looks when she explains that she’s from Luton: “She told me, ‘I’m not sure I would have gotten my job if they had known I was from Luton first’.”

“Integration is such a loaded them – there’s an automatic assumption there’s something not quite right in the community – and people often fail to recognise integration is a two-way street,” says Imrana Mahmood, a teacher and creative producer. “Things have improved in Luton and even though the perception from outside is that Luton is segregated, if you talk to people here, it’s not like that at all.”

Her words are echoed by various people – from white to Asian, Muslim to Sikh – everyone seems defensive about Luton’s reputation but when it comes to integration, opinions vary.

Balal, a bus driver waiting at the station tells me his community still needs to open up more as they are “not very educated yet”. “The Asian community want everything in the UK but some are not prepared to adapt – I’m not saying to forget our culture, but some people are narrow-minded,” he says. “If you live in this country, you need to integrate.”

A white woman tells me she’s uncomfortable with people who complain about integration or special treatment of minorities so she just “doesn’t pay attention”. “Look at the royal family, even they’ve become more mixed, that’s the way it’s going to go.”

Keith says he understands why some people are uncomfortable with the large minority communities in their town. “I go to Eastern European bakeries and shops and can’t read anything in the shop because everything is written in Polish, for example, but I find them really exciting places to be in,” he says.

Keith doesn’t feel Luton has changed much in the decades he’s lived here as he says people have always been interacting on the ground. “Everyone I know, from the rugby club, the cricket club and the pub – it’s always been a mixture of people,” he says.

Keith believes the evolution of local communities is natural: “When I first came here the area was very Irish and they were a close-knit community – I don’t see any difference between that and some communities today.”

Walking around Bury Park is a colourful experience. This small area of Luton with terraced houses, south Asian shops and vegetable stalls has been scrutinised by the police in the past and is now regularly patrolled, especially on Fridays.

Bury Park was accused of being a “no-go zone” by Britain First. Former Prime Minister David Cameron even chose a Bury Park school to unveil his counter extremism strategy. Fatima’s father owned a restaurant in Bury Park for many years and she still has family working there. She describes the various histories of the shops with the familiarity of someone who has walked these streets for generations.

As we pass a house with a prominent security camera on a street corner, I’m airily told it used to have a huge British flag hanging in front and is owned by “racist people”. “Everyone knows – they will never hurt you, but you know they’re racist,” says Fatima. “I do get a bit scared if I’m coming home late from the station and have to walk this street.”

Despite the melting pot of ethnicities (including white British) immediately obvious around Bury Park, Imrana says there is a perceived fear among some that white people are unwelcome. There is a football club in the area and I’m jokingly told that if there are more than five white people together in Bury Park, it must be because of a football match.

During an exhibition by photographer Peter Sanders on positive representation of Muslims, Imrana talked to an older white couple. “From the outset, I could see he had probably never spoken to a Muslim before,” explains Imrana. “He said ‘you people don’t integrate’ and spoke about how the British had to sacrifice their lives during World War 2 and then ‘when you people came you wanted to change things’.” (As a matter of simple fact, nearly 80,000 soldiers from the Indian subcontinent died for Britain during the war.)

Imrana says she’s noticed this perception of Muslims mostly through her work and has gone out of her way to challenge it.

When I ask Fatima about integration, she laughs and tells me she was at a café in Bury Park with a white friend yesterday. “We sat there for an hour and people coming in were speaking Urdu, Bahari, Bengali, Punjabi and English – that for me is integration,” she says. “People were code switching, going from one language to another, the children with their own form of slang.”

Fatima stresses that integration should not only be centred on people from ethnic minorities interacting with white people. She points out a Halal meat shop in Bury Park, telling me there is usually a long queue made up of a mixture of people, from Afro-Caribbean to Eastern European to Asian to white. “People who walk these streets are interacting, building friendships, recognising each other so it’s there, on the ground, at grassroots level but that’s not something the officials are interested in.”

Speaking English has increasingly become emphasised as a method of integration. Two years ago, David Cameron said more Muslim women should learn English and Dame Louise Casey, who reviewed community cohesion and extremism for the government, said this year that everyone in the UK should speak English by a set deadline.

But some Lutonians don’t think this a sensible measure. “I don’t think there’s any way to force that. My friend is Sri Lankan and his grandmother doesn’t speak English – she refuses – and there’s no way in the world you’re going to force her,” says Keith. “These things take time, you have to focus on the children.”

Fatima agrees, saying it’s a “very colonial way of looking at ethnic minorities”. She says there is a perception that you are not contributing to the country if you don’t speak English.

When asked about issues with integration, several pointed to the negative impact of government cuts on communities. “Integration in this country is such top down approach, especially with austerity. If you’re cutting funding to areas seeing problems in society, you’re part of the problem,” says Fatima.

Funding cuts are reducing public spaces available for people to come together and meet as well as reducing opportunities for the youth.

Daniel, a young white man who works at a travel centre, doesn’t understand why integration is considered the main issue in Luton: “It doesn’t really mean anything, you just have to not be racist – integration is not the problem here, it’s the drugs.”

Like in many other towns, drugs are a severe problem in Luton and have affected all the communities living there. Keith agrees. “Yes, we do have killings, but every single town has that. A lot of it is down to drugs, not down to cultural or racial differences.”

“When I pass by a school and see kids playing, no one really cares [about ethnic and religious differences], the kids don’t care. That’s my hope for the future,” says Keith.

Keith, who is half-Irish, says the same thing happened in Northern Ireland, where only a few families “care about the vendetta between the Catholics and Protestants because the kids who played together grew up without the same hate”.

Keith gives art classes in Luton and he says most people come in to have a chat and coffee as much as they come in to produce art. “When you get people out of their normal environment and interacting with other people, things change so fast.”

When asked what could improve community cohesion, he suggested drop-in centres where people could walk in and learn more about other communities.

Imrana created a book club that meets in Bury Park, initially for Muslim mums, that soon encompassed different cultures, religions and ages. She says it’s not “about tolerance because tolerance itself is a low bar to set, it’s about acceptance and love, and how we, despite our differences, work towards a common goal”.

But she warns that the constant need to “humanise” Muslims can be problematic when attempting to show “integrated minority communities”. “We need to be accepted for who we are and the media doesn’t help by linking anything negative happening in Luton to its extremism narrative,” she adds.

Michael Singleton, a retired teacher and Chair of Churches Together in Luton, agrees with Imrana’s approach, stressing it is important that community work isn’t just done by faith leaders and activists but by everyday people interacting positively.

One Lutonian suggested more “top-down” efforts to tackle diversity problems in companies through unconscious bias training but also by addressing the middle management glass ceiling for black and Asian people.

Nearly everyone I spoke to pointed to schools as a way people are interacting organically. “No one is forcing the kids to interact with each other, but it’s happening naturally.” says Fatima.

However, schools are not always mixed due to admission rules and catchment areas and Fatima admits this limits interaction between ethnic minority and white students.

Predominantly white areas such as Farley Hill have predominantly white students while areas with a certain ethnic minority will have schools dominated by that ethnicity. “So the government and local council policies on how you admit pupils in schools also determines interactions,” Fatima adds.

Since February 2016, HOPE not hate has travelled to over sixty different towns, cities and rural communities across all regions and nations of the UK as part of the National Conversation on Immigration, the largest public engagement on immigration ever undertaken. Together with British Future, we’ve had over 130 conversations with ordinary members of the public and local stakeholders about all aspects of migration.

What has been striking in our findings are not just distinct local differences in attitudes, but also the centrality of integration in shaping attitudes towards others.

Everywhere, we’ve had nuanced and constructive debates about migration. Much is positive, but the conversations can also be cathartic, as participants air their anxieties and fears. Many voice concerns about ‘control’ or criminality, about migrants adding pressure to public service or abusing welfare benefits. Often, people link their concerns about immigration directly to integration:

“Overall, it [immigration] is more positive than negative, but there are some exceptions. If you go somewhere you have to embrace it, embrace the language, embrace the culture”

Participant, Berwick-upon-Tweed

For most people, integration is not assimilation, but comes down to mutual respect, tolerance and understanding. Fears about integration often stem from perceptions that for settled communities, there is more give than take.

Where residents have meaningful social contact with migrants, they are able to base their opinions on these social interactions, rather than on “community narratives” drawn solely from the media and peer group debate. But not everyone has meaningful contact with people who are different from themselves, and perceptions that integration is not working are reinforced by encounters which seem to confirm suspicions.

The pace of change in some places has felt overwhelming. While people generally mix well in workplaces, some people we’ve spoken to have felt uncomfortable working in factories or warehouses alongside EEA nationals with whom they cannot communicate, and feel their working environments have become less cordial as a result. It is not that people don’t want to mix, but they sometimes feel that migrants do not want to be part of their communities, especially where they feel their efforts to be welcoming are rejected.

Participants are generally positive about the role of schools in promoting good community relations, and feel that children in schools mix well and learn about each other’s cultures. But they often feel that parents keep themselves to themselves, and see language barriers responsible for much of this. Simultaneously, stakeholders in almost every place we’ve visited have told us that English language classes are inadequate, or do not meet the needs of migrants working long hours or with young children.

Often, integration problems are seen to be concentrated in certain areas. People we have spoken to often cite cities such as Birmingham or Bradford as areas they fear, where they believe immigration has “taken over” and resulted in a loss of English identity. Sometimes these comments are in response to the changing look and feel of the UK’s towns and cities, but low-level anti-Muslim prejudice underpins much of these sentiments. While not always explicit, people commonly raise concerns about a lack of compatibility of Islam with a British way of life, often in areas with less diverse populations.

It is not uncommon for participants to cite media stories about bans on nativity plays or tell us that they feel unable to express their national identity. While pro-migration camps may ridicule these narratives, it is worth understanding that these stories stick as they resonate with some people’s broader outlook. If we are to shift the narrative rather than reinforce divisions, we need to find better ways to engage with people on integration issues who do not see immigration and multiculturalism working for them.

“You hear certain people say ‘don’t go to this area’, it’s like Chinese whispers going around. I think that could be detrimental to people wanting to get to know each other.”

Participant, Preston

Sometimes, integration concerns are voiced in reference to particular neighbourhoods. Often these are in poorer areas with cheap, private rental accommodation but little infrastructure to accommodate the new populations moving in. As one stakeholder in March told us, “You’ve got one house or a flat, but with ten times the rubbish outside and six times the number of cars”. Associations made between migration and neighbourhood decline feed concerns about a lack of integration, and perceptions that migrants are not respecting the ‘British way of life’.

Further, perceptions of ‘failed integration’ can inform wider concerns about control. For example, when we visited Bolton, ‘undesirable’ migration and a perceived failure of integration were automatically linked. Members of the panel thought that ‘genuine’ claims for asylum could be identified through claimants’ willingness to integrate, and that migrants seeking benefits could be spotted through a lack of respect for British culture.

People also tell us where they think integration is working. Most people think schools are doing a good job in actively promoting positive diversity and helping children to mix well. We are also told where integration works well organically and often goes unnoticed, such as in workplaces or sports clubs. People really value community initiatives that draw people together, or inclusively celebrate events. These not only help people to meet and better understand one another, but can help build an inclusive civic identity.

Social contact between migrants and local residents is key to integration, and to improving community relations. But social contact cannot be forced, and is not always possible. Further, negative encounters can have a forceful effect and reinforce an underlying view that people from different backgrounds do not mix well. It is clear that tackling a number of issues such as English language provision, or residential segregation are important. But we also need to start challenging dominant narratives that multiculturalism is not working. We need to find better ways to engage with those who hold anxieties, so that is not just those peddling anti-migrant or islamophobic views who are heard.

I’ve spent the last few years studying and documenting the demographics and voting behaviour of people who were voting for UKIP in local and national elections. This process meant I often found myself in towns rather than cities, since it was in towns like Grimsby, Oldham, Dudley and Rotherham that former Labour supporters were most likely tempted to vote for UKIP. In discussing their reasons, it quickly became apparent that the characterisation of such voters as ignorant racists was wide of the mark by some distance. Voters often expressed longstanding economic challenges in the towns they lived in, and much more pragmatic concerns about immigration than you might believe if you read their somewhat hysterical representation in the media.

In setting up the Centre For Towns we wanted to push back against the unfair characterisation of such places and provide a platform for more research into the challenges they face. At the Centre For Towns we recognise the importance of historical context when trying to understand the importance of place. Without an explicit recognition of how towns have changed over time, we shouldn’t be able to describe why such towns are often the context for racial tensions and fertile territory for political parties like the BNP or UKIP. In recent years, towns like Grimsby, Hartlepool, Oldham, Dudley, Burnley, and Rotherham have seen UKIP take votes from the Labour party as concerns about immigration reached a peak in around 2015. However, the political impact aside, those towns have too often been unfairly characterised as ‘left behind’; an unfortunate label which too often is shorthand for ‘backward’ or ‘ignorant’.

Residents of all backgrounds in our towns face significant economic challenges. The last fifty years have seen significant and profound changes visited upon them. The decline of manufacturing from the 1960s onwards resulted in hundreds of thousands of job losses in industrial towns across Britain. Many of our industrial towns were also the destination of choice for immigrants from the second world war onwards. So, when the decline in manufacturing came it impacted on both immigrant populations and the white British residents of such towns. One example of such a process highlights how this decline in manufacturing impacted on both white British and Pakistani households; the Mirpuri immigration of the 1960s.

A little over fifty years ago the construction of the Mangla Dam in the Mirpur district of Kashmir in Pakistan submerged hundreds of towns and villages, leading to the displacement of thousands of Mirpuris. The British dam constructor provided legal and financial assistance to the displaced, many thousands of which were granted visas by a British government in need of workers for its textile factories across the north of England; some of which made their home in the town of Oldham. The recent male immigrants and white residents of Oldham were both ill-equipped to deal with the decline in manufacturing when it came from the 1960s onwards.

By 2016, Oldham was reportedly the most deprived town in England. However, it is also one of the towns with highest levels of inequality between its white and non-white population. There is still a disparity between employment, health and education outcomes are worse for Asian residents than they are for white residents. Four in ten of residents in Oldham do not have a qualification. Health outcomes are amongst the worst in the country. Both communities have suffered, and whilst recent political advances by UKIP in the town provide a convenient outlet through which to express anger at this suffering, we believe the story of Oldham is one which requires a community-wide and overwhelming response from central government. Only by such an overwhelming response can towns like Oldham recover.

For while the town of Oldham still struggles to adjust to the realities of the decline of its manufacturing base it is by no means on its own. Towns and communities across ex-industrial Britain have faced similar challenges, and for too long have been left out of economic models which see highly-skilled cities as the only engines of economic growth. Successive governments have appeared to pay lip service to the challenges faced by towns like Oldham, preferring instead to advocate for high-skilled, white collar employment. Underlying the shift from manufacturing to high-skilled employment was an assumption that places were equally capable of making that shift. However, the shift inevitably favoured places with access to skilled workforces and marginalised those with workforces with non-transferable skills in manufacturing. These shifts produced significant geographical patterns in unemployment both for white and non-white residents of our towns.

Little surprise then that the residents of such places view central government and politicians of all parties with suspicion. They have long felt ignored by Westminster, believing that politicians are not interested in ‘people like them’ or the places where they live. This combination of economic decline, high levels of inward immigration and record levels of dissatisfaction with mainstream politics provided a space for populist right-wing parties like the BNP and UKIP to drive a wedge between communities in places like Oldham.

The demise of the BNP, and the slow death of UKIP, are to be celebrated for those of us on the progressive side of the aisle. However, the belief that the anger and disaffection they catalysed has disappeared is a dangerous illusion. Only by meeting the multi-faceted challenges faced by ex-industrial towns across Britain can we hope to head off the next populist right-wing challenge. Failure to do so will condemn us to fighting repeated manifestations of this anger, rather than dealing with the conditions which invoked them.

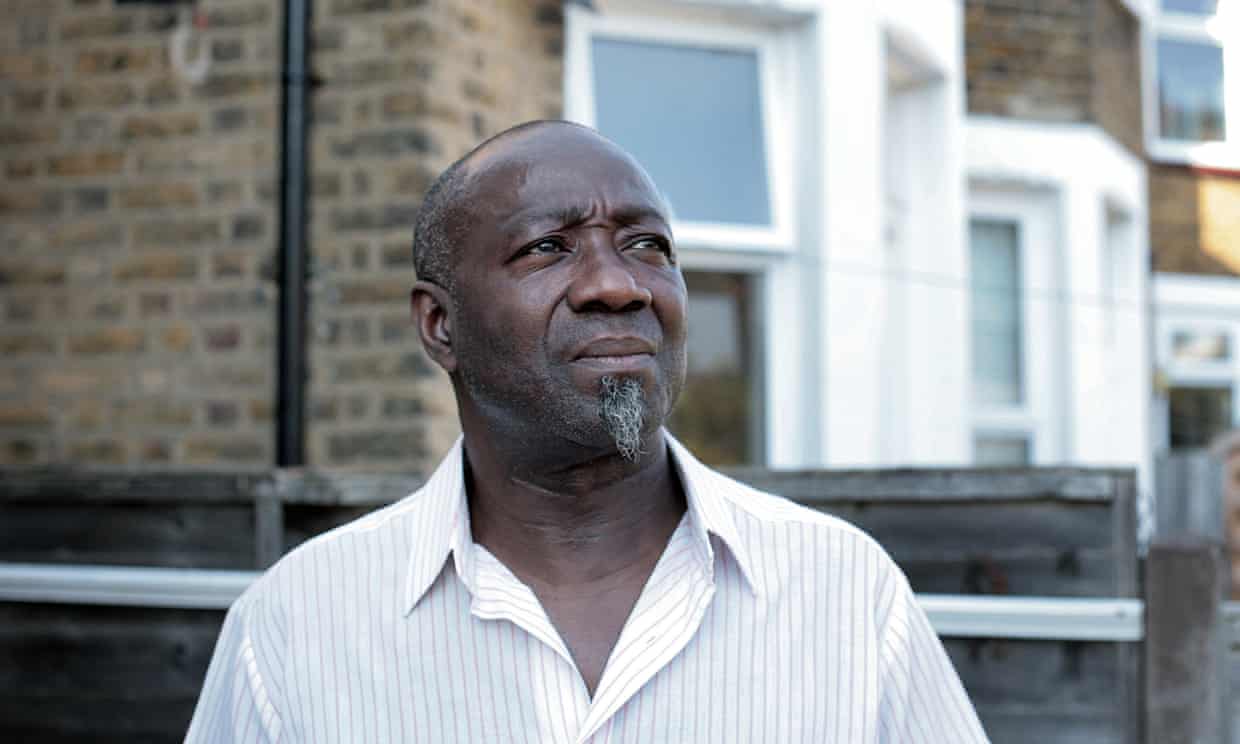

They are the children of the ‘Windrush’ generation, welcomed to Britain from the Caribbean as a response to post-war labour shortages. They worked and paid taxes for decades, assured they were British through their Commonwealth status.

Now their future is under threat. Some, mostly from low-income backgrounds, have been put under tremendous pressure to prove their ‘Britishness’. Jobs and homes have been lost, healthcare has been denied and several were sent to detention centres and threatened with removal to a country they hadn’t seen since they were children.

Despite being here legally, many have never formally naturalised or applied for a British passport and with the successive tightening of immigration rules, most controversially under the Home Office’s “hostile environment policy”, they are unable to prove their status.

“They tell you it is the ‘mother country’, you’re all welcome, you all British. When you come here you realise you’re a foreigner and that’s all there is to it,” says John Richards, one of the original passengers on the MV Empire Windrush, which arrived in Essex in 1948.

Around 500 settlers from Jamaica, many of them ex-servicemen, arrived on the ship. This was the first wave of Britain’s post-war drive to recruit labour from the Commonwealth to cover employment shortages in state-run services like the NHS and the London Transport.

‘I’m British and have lived here nearly all my life, so why must I leave?’ Glenda Caesar is part of the ‘Windrush Generation’, one of thousands of Caribbean immigrants who now face an uncertain future https://t.co/LQhyhbfUzm pic.twitter.com/vP6C5MO5Sv

— ITV News (@itvnews) April 12, 2018

The so-called ‘Windrush children’ like John have lived in the UK for most of their lives, legally allowed into Britain to address the labour shortages at the time.

Because they came from British colonies that had not achieved independence, they arrived as British citizens. But as successive governments set increasingly harsh immigration regulations, they were suddenly required to justify their presence by producing decades-old paperwork.

In recent days, the issue has exploded onto our screens, with the Caribbean leaders arriving for the Commonwealth conference, revelations that landing cards were destroyed, and a very public row between the political parties over blame, with fumbling apologies coming from the Prime Minister.

There has been public outcry across the political spectrum as stories emerge from a son unable to return to bury his mother, to a grandfather refused cancer treatment, to a man sacked from his job, denied benefits, classed an illegal immigrant for having no passport and dying on the street.

Monish Bhatia, a lecturer in criminology at Birckbeck University of London, specialises in undocumented migrants. He says the current immigration policies are “racist” and have been shaped over decades to be “intentionally cruel.”

Story after story has emerged of Commonwealth citizens arriving decades ago, working and paying their taxes only to be made homeless, prevented from accessing healthcare and other government services because they could not find the necessary proof they had been in the country for decades.

Part of the problem has been a requirement to provide four pieces of evidence for each year that a person has been in the country.

Junior Green arrived here as a baby in England aged just 15 months, in January 1958. He has lived in Britain his whole life. After a short trip to Jamaica to visit his dying mother, he was not allowed back into the country and missed her funeral.

Junior Green has lived in the UK for 60 yrs since 1958. He returned to Jamaica to be with his dying mother. Her body was repatriated to the UK and he was not allowed to attend her funeral. I am disgusted. Justice must be done and will be done. #Windrush pic.twitter.com/1gqovRzTIT

— David Lammy (@DavidLammy) April 18, 2018

Nick Broderick revealed to the BBC he had contemplated suicide if he was deported to Jamaica, a country he’d left as a baby in 1962. Renford McIntyre told The Guardian he had lived in the UK for almost 50 years and was now homeless, after being told he was not British and therefore was not allowed to work or access any government support.

“Windrush generation” of Caribbean migrants facing threat of deportationhttps://t.co/V5ewUnwP9r pic.twitter.com/kjXtYzwln1

— BBC News (UK) (@BBCNews) April 13, 2018

Over the last few days, increasingly horrifying revelations have emerged as the Windrush generation have become front page news. It was revealed that officials destroyed the landing cards which could have helped support Windrush cases, despite warnings from staff.

Until this week, the government has remained silent when challenged over the treatment of these British citizens. Prime Minister Theresa May had refused to intervene when it emerged a man was denied cancer treatment until he could pay a £54,000 bill or prove his citizenship. She had also rejected a meeting requested by leaders of the Caribbean countries to address the matter.

When Home Secretary Amber Rudd was asked if there had been wrongful deportations, she said she would have to meet Caribbean High Commissioners urgently to “find out if there are any such people who have been removed”.

The Windrush scandal has united people from across the political spectrum. Both Labour and Conservative MPs have spoken out against it and even the Daily Mail, notorious for its anti-immigrant stance, has provided sympathetic coverage.

A petition launched to give amnesty for anyone who arrived in Britain between 1948 and 1971 has received over 170,000 signatures, although some people have objected to the word “amnesty” – believing it implies the Windrush generation were not legally entitled to live in the UK in the first place.

This week, the government has done a U-turn with both Rudd and Prime Minister Theresa May issuing apologies for the “appalling” treatment of these immigrants and May agreeing to a meeting with the leaders of Caribbean countries.

A taskforce has been set up and application fees have been waived with May even promising compensation will be given to those already affected.

The rapidly emerging scandal is all the more stark because of the Commonwealth Games celebrated earlier this month, with Prince Charles opening the games and mentioning in his speech “… the potential of the Commonwealth to connect people of different backgrounds and nationalities.

Richard Sudan, the grandchild of a Windrush immigrant, writes in The Independent that in the wake of Brexit, Britain is hoping to emphasise Commonwealth relations but that the ‘Windrush’ scandal is revealing.

“Britain has never fully faced up to its own violent, colonial past. Now, as a result of economic decline, Britain is dealing with an accelerated crisis of identity, having never had an honest conversation with itself about its true history. Many people want to deny the past, even though it has shaped our multicultural society today. They instead seek to blame victims of the system, the people who helped to build it, for all of society’s wrongs.”

Labour MP David Lammy condemned the government this week in the House of Commons, saying:

“The first British ships arrived in the Caribbean in 1623, and despite slavery and colonisation, 25,000 Caribbeans served in the first and second world wars alongside British troops.”

When my parents came here they arrived as British citizens. This has come about because of the hostile environments policy begun by Theresa May. If you lie down with dogs then you get fleas. This is where so much anti-immigrant rhetoric gets us #Windrush pic.twitter.com/qTF3Va5dq9

— David Lammy (@DavidLammy) April 16, 2018

He added: “This is a day of national shame, and it has come about because of a ‘hostile environment’ and a policy that was begun under her Prime Minister. Let us call it as it is: if you lay down with dogs, you get fleas, and that is what has happened with the far-right rhetoric in this country.”

The hostile environment was an essential part of the 2014 and 2016 Immigration Act, with then-Home Secretary Theresa May boasting of creating “a really hostile environment” for immigrants.

Sometimes called the “compliant environment”, the policy’s aim was to create a situation where [supposedly illegal] immigrants could not access services, either public (NHS, welfare) or private (employment, rented housing, bank accounts) unless they could prove their right to be in the UK.

The requirement to prove status has caused a great number of difficulties for many Windrush children, who have never applied for passports and did not retain proof of their residency for every year they lived in the UK.

There is no concrete available data on how many people could end up in this position but some estimate over 50,000 British citizens could be affected.

Rob Ford, a professor of political science at the University of Manchester and expert on the politics of immigration, says that these stories are only now being heard because the people affected often have very little contact with government agencies.

“They tend to be in irregular employment or retired; they are often people who have never travelled abroad since they came here and have no official documents so are essentially running against a brick wall,” he says.

Ford says that when the “hostile environment” was put into place, the government was warned by civil society that this would be the result.

“They knew that there was a segment of the public that had been here for many years that had no passports and they did not do anything to provide some sort of solution when it came up, they just left it and this is where we end up today.”

Bhatia says successive governments’ regulations have contributed to the state of immigration today.

“In 1969, it was Labour that took over an introduced the immigration appeal act which set conditions for entry and institutionalised deportations for the first time,” he says.

Ford adds that Enoch Powell’s speeches happened in reaction to two pieces of Labour legislation: The 1971 Race Relations Act and the Commonwealth Immigration Act of 1962 which was “anti-immigration” and occurred because “the Wilson government was massively spooked by the public’s reaction to the Kenyan Asian crisis”.

Kenyan Asians had their British citizenship retroactively revoked to prevent them from easily coming into Britain. Ford says one of the reasons the Race Relations Act passed was to “blunt the impact” of the first Act. “This was the first time the pairing of good race relations and tough immigration control was made explicit,” he says.

Gary Younge writes in The Guardian that Britons must ensure the “rightful outrage about the exclusion of those who are now, finally, perceived as “worthy immigrants” does not blind us to the outrageous immigration policies that made such exclusion possible and will continue to exclude others deemed “unworthy”.

He adds: “The mistake the government made was assuming the woes of a few elderly black people born in the Caribbean could not prick the nation’s conscience. They underestimated the pull the Windrush generation could have on Britons’ sense of self.”

The Windrush cases have fuelled concern over how EU citizens will be treated after Brexit and how other immigrant groups are surviving Britain’s hostile environment.

Bhatia suggests the current Windrush scandal could be used to reassess the kind of immigration controls in place.

“We need to talk about how border controls are affecting different group of people, the types of harms it is generating and the government policies that are incredibly racist.”

The stories being told about the hardships faced by the Windrush generation do not exist in a vacuum, as less “worthy” immigrants deal with being illegally detained, going on hunger strike to protest poor conditions or being ill and removed only to later die.

There are countless witnesses of lives being thrown into turbulence as immigrants crash with policies that are increasingly hostile and bureaucracy that only grows more intransigent.

HOPE not hate’s exclusive polling lays bare the extent of fears and anxieties about multiculturalism and integration in the UK.

Two fifths of Britons do not think multiculturalism is working. Slightly more, 43%, think that relationships between different communities within the UK will get worse over the next few years, while just 14% believe things will get better.

A depressing 40% of people think Enoch Powell’s dire predictions of communities at war with one another has proved to be correct. Only 41% of people think he was wrong.

It is clear we still have a long way to go to lift pessimism about modern, diverse Britain.

HOPE not hate believes that understanding where we are now, no matter how grim the figures may look, is essential to improving things. But we also know that action is needed.

Issues around integration are some of the major challenges facing the social fabric of this nation. With perceptions that integration is failing, coupled with a rapidly changing population, there is no issue that is more important for society to get right. For if we cannot get integration right now, what hope do we have by 2050 when the BAME population is expected to reach 36%?

Today, 50 years on from Enoch Powell’s rivers of blood speech, HOPE not hate is launching a new Integration initiative to challenge the growing perception that integration is failing and a concerted right wing narrative that multiculturalism cannot succeed because of the inherent incompatibility of Islam with western culture, which is becoming increasingly mainstream.

The project will recognise the many serious challenges we face around integration and it will not shirk from addressing difficult issues. Our integration project will be a multi-faceted operation, combining research, polling, policy engagement, highlighting good practice and working in local communities.

Our integration project is built around six key elements:

We will engage in the political and policy debate around integration. With opinion polls showing that most people have a pessimistic view on integration and each terrorist attack further reinforcing this view, politicians and policy makers are continually rethinking how best to create a more cohesive society.

In 2010 David Cameron announced that muscular liberalism should replace multiculturalism, which he said had failed. In 2016, the Casey Review called for the traditional integration approach to be replaced by assimilation.

In 2017, in the wake of the Manchester terrorist attack, Theresa May conflated integration with violent extremism. Just last month, the Government released a Green Paper on integration which changed approach yet again and reverted to a more traditional two-way street approach to integration. Government ministers and policy makers are clearly divided on the issue.

Few progressive voices are heard in these processes, and with many people preferring to focus on implementing integration at local level there is a real absence of debate and ideas emanating from more moderate voices at a national level.

While there has been understandable frustration with the nature and focus of much of the Integration debate, particularly with how it is often reported in the press, we believe there has been no better time to engage with politicians and policy makers to offer a positive approach.

Pessimism on these issues is unsurprising given public and political debate, much of which reinforces an argument that multiculturalism has failed, and that Islam is incompatible with British culture.

Narratives espousing views that were once marginal have become increasingly accepted and sensationalism and scaremongering about Muslims in Britain is rife across mainstream media. And half a century on from Enoch Powell’s Rivers of Blood speech, Douglas Murray’s, The Strange Death of Europe, offers a revived version of Powell’s ominous manifesto, to argue that in fact the situation is much worse than Powell’s foreboding message anticipated. Yet unlike Powell’s disgrace, Murray’s book won multiple awards and spent months at number one on numerous bestseller lists.

On the other side, those who value diversity can all too often become defensive, offering a celebratory view of multiculturalism which fails to acknowledge any integration issues. The reality is that multiculturalism has been an uneven success linked to wider socioeconomic inequality, leaving some areas of Britain more integrated than others.

While optimistic views are reflective of many areas of the country, our research shows they tend to be held by those who are younger or economically secure, often highly educated and middle class. They fail to resonate with those who do not see multiculturalism working for them.

Just like the toxic immigration debate, which played a big role in the vote to leave the EU, we need to join the conversation on integration and multiculturalism. Whether we like it or not, these discussions are going to happen. It is not enough to look on as voices wrongly claiming ‘multiculturalism has failed’ continue to shout loudest.

Ignoring concerns in order to champion the opposite is ineffective, and can drive further resentment. We need to challenge the idea that multiculturalism has failed, and develop messaging which can challenge people’s anxieties and perceptions of failed integration in a way that can resonate and to have meaningful impact on shifting attitudes.

Eight years of HOPE not hate research has highlighted the link between economic insecurity and pessimistic attitudes to immigration and multiculturalism. Concerns about immigration and multiculturalism do not stand in isolation from a sense of injustice or loss in how people see their own lives, for which migrants are often blamed.

A sense of dissatisfaction with peoples’ own lives often translates into resentment of others, but attitudes are flexible and change with external conditions. Our Fear and HOPE polls have tracked growing liberalism where there is access to opportunities, and a drift towards hostility where there is declining living standards, joblessness, casualisation of labour, and cuts to public services.

Recently we developed an immigration heat map for each of our six Fear and HOPE tribes, allowing us the measure the propensity for anti-immigrant and far right views onto small geographic areas of around 500 houses. This allows us to see national trends, to understand how the environment influences attitudes and look in greater detail at the drivers of hostility.

It is perhaps no surprise that hostility is concentrated in areas where there is little opportunity, predominantly towns which have seen major decline and post-industrial areas. Conversely, the most liberal views are concentrated in cities, in middle class areas nearby universities, areas with a wealth of opportunity.

If economics continue to be a central driver of negative attitudes towards others, no amount of alternative narratives or community work to build resilience or integration initiatives will be able to counter the tensions and fears exposed in our polling unless we also take economic inequality seriously.