HOPE not hate uses cookies to collect information and give you a more personalised experience on our site. You can find more information in our privacy policy. To agree to this, please click accept.

Welcome to Heroes of the Terraces: Football, Anti-Fascism and Protest, the third in our Heroes series. Like the previous two, Heroes of the Resistance and Heroes of the Civil Rights Movement, this special magazine remembers and celebrates all those who have stood up to racism, fascism and prejudice –with this edition focused on football around the world over the last 100 years.

Heroes of the Terraces recounts the players, supporters and clubs that have fought bigotry on and off the pitch. We tell the stories of those clubs that have anti-fascism running through their DNA. We remember how fascist and authoritarian regimes have tried to use football to win support for their murderous regimes and how players and supporters, often at huge personal risk, refused to obey. We recount how football triggered wars, but also helped heal conflicts. We celebrate excellent anti-racist fan initiatives and explore how football fans have been at the centre of many popular uprisings in recent years. And, most poignantly for today, we applaud the current crop of players who are backing or even leading social justice campaigns.

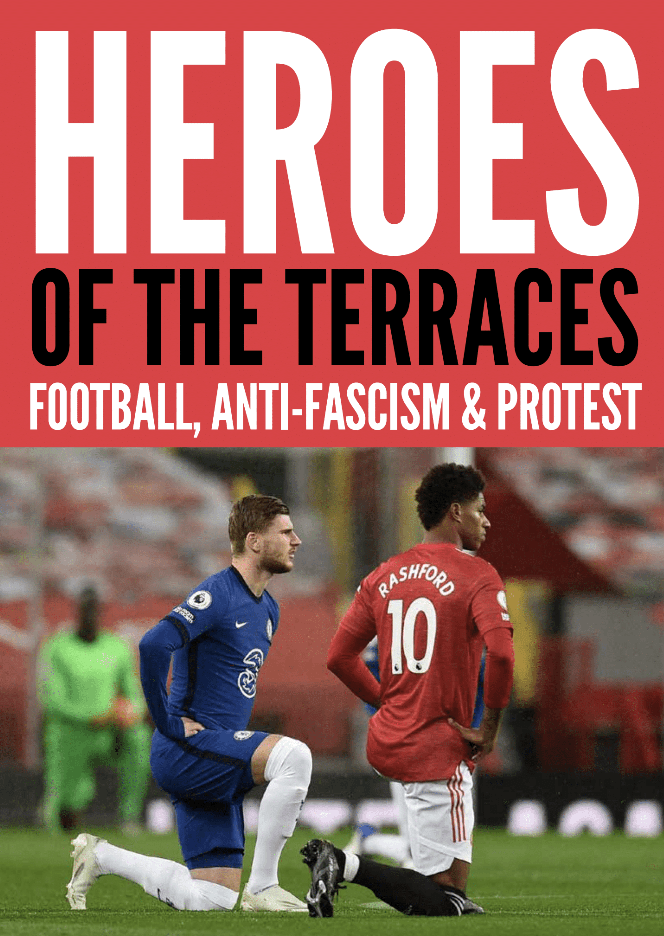

This magazine comes out shortly after the failed attempts to create a European Super League and the end of Euro 2020, which once again demonstrated the strength of player and fan power. The billionaire owners of the richest clubs were humiliated in a fan uprising and the England team refused to bow to the pressure of politicians and Government ministers who objected to them taking the knee. The British public reacted to the racists who abused the three black England players who missed penalties with an outpouring of defiance and solidarity.

Racism continues to blight football. It causes misery for its targets and robs joy from those who fear being targeted. Sadly, opposing racism remains an uphill struggle, with those who speak out often targeted, abused and even punished.

But at the same time, football has the potential to create real change and this is what we’ve tried to capture in Heroes of the Terraces through retelling stories of people standing up to racists, offering solidarity to those targeted or using their collective strength to demand change.

The Heroes series is our way to remember and recognise those who campaigned and fought for equality and against extremism across the world. It is also designed to inspire us to continue the struggle in the future.

We hope you enjoy this publication as much as we enjoyed writing it.

In Heroes of the Resistance, which recounted the stories of those who stood up to the Nazis in WW2, we wrote “we remember their bravery in order to honour them. While we mourn humanity at its worst, we also celebrate humanity at its very best.” This is as true about those standing up to racism, fascism and prejudice in football as it was for those fighting fascism in World War Two.

Below, you can read selected chapter from this amazing publication. To get the full 135 page magazine, visit our shop to buy a copy. It is a great read, and your purchase means supporting our work.

Welcome to Heroes of the Terraces: Football, anti-fascism and protest, the third in our Heroes series. Like the previous two, Heroes of the Resistance and Heroes of the Civil Rights Movement, this special magazine remembers and celebrates all those who have stood up to racism, fascism and prejudice –with this edition focused on football around the world over the last 100 years.

Heroes of the Terraces recounts the players, supporters and clubs that have fought bigotry on and off the pitch. We tell the stories of those clubs that have antifascism running through their DNA. We remember how fascist and authoritarian regimes have tried to use football to win support for their murderous regimes and how players and supporters, often at huge personal risk, refused to obey. We recount how football triggered wars, but also helped heal conflicts. We celebrate excellent anti-racist fan initiatives and explore how football fans have been at the centre of many popular uprisings in recent years. And, most poignantly for today, we applaud the current crop of players who are backing or even leading social justice campaigns.

This magazine comes out shortly after the failed attempts to create a European Super League and the end of Euro 2020, which once again demonstrated the strength of player and fan power. The billionaire owners of the richest clubs were humiliated in a fan uprising and the England team refused to bow to the pressure of politicians and Government ministers who objected to them taking the knee. The British public reacted to the racists who abused the three black England players who missed penalties with an outpouring of defiance and solidarity.

Racism continues to blight football. It causes misery for its targets and robs joy from those who fear being targeted. Sadly, opposing racism remains an uphill struggle, with those who speak out often targeted, abused and even punished.

But at the same time, football has the potential to create real change and this is what we’ve tried to capture in Heroes of the Terraces through retelling stories of people standing up to racists, offering solidarity to those targeted or using their collective strength to demand change.

The Heroes series is our way to remember and recognise those who campaigned and fought for equality and against extremism across the world. It is also designed to inspire us to continue the struggle in the future.

We hope you enjoy this publication as much as we enjoyed writing it.

In Heroes of the Resistance, which recounted the stories of those who stood up to the Nazis in WW2, we wrote “we remember their bravery in order to honour them. While we mourn humanity at its worst, we also celebrate humanity at its very best.” This is as true about those standing up to racism, fascism and prejudice in football as it was for those fighting fascism in World War Two.

We salute all those who take a stand against racism and fascism and promise to continue the fight for HOPE over hate. We hope you will join us in our quest.

This article is published in Heroes of the Terraces, a new publication from the HOPE not hate Charitable Trust. Read more selection articles and find out how to get a copy of the magazine in the Heroes hub.

Matthew Collins on the battle against those who would defile the beautiful game with hate, and the hopeful signs that fans are uniting against racism on the pitch and in society.

The comparative description of football as “working class ballet” is widely attributed to Alf Garnett, an English caricature of an aged white Londoner spanning two decades (until 1986), who had tired of the modern world and multiculturalism in particular.

Garnett’s character was symbolic of a period of British television comedy that explored (and undermined) an increasingly multicultural and diverse modern country.

It was an exploration that just went wrong. There was no calculated malice; just endless portrayals of non-white characters as simpletons and servants at odds with aggressive, rather dull but complicated white protagonists whose logic and language was condescending and racist. Garnett even populised the use of ‘the Yids’ as a term of abuse for Spurs fans.

Much of that comedy is now locked away, with even the Gold channels not willing to show it. But type ‘working class ballet’ into Google and this notion of the beautiful game is widely quoted, almost revered around the world. The loveable, cockney racist whose off the cuff utterance it was, is widely omitted.

My first (and still) footballing hero was a Black Londoner named Vince Hilaire who rejected the glamour and pedigree of the world famous West Ham United to play for his local, dour club Crystal Palace. A couple of years ago I was writing an article and wanted to recapture that Hilaire emotion. I found an old news item, on Youtube, and Palace’s then manager, Allan Mullery, speaking about the young man in front of him said ‘he’s got a lovely tan’. Life imitates art, it is also said.

In Britain, working class ballet has been described by legendary Liverpool manager and socialist Bill Shankly as more important than simply life or death. Even ballet, with its graceful contortions of the human body to classical music, has caused less torment, pain, disgust and outrage than football. And nobody, nobody ever has been to war over the outcome of Swan Lake.

Football is tribal in the best and worst of traditions the world over. From the workers teams’ of the Soviets and the Partisans and Brigdistas of the former Yugoslavia and the East, to the factory teams of Manchester and the German automotive industry.

From the torment and squalor of the Irish immigrant and catholic tenements in Liverpool, Edinburgh and Glasgow have come world class football clubs and from that same torment and sectarianism on the streets of the west of Scotland, murders most foul.

Researching the Hillsborough tragedy reminded me of a time when society portrayed all football fans – including those whose lives were so tragically and criminally lost – as wild, unrepentant savages. As the establishment covered up the wrongdoings of the police, their prejudices about football fans couldn’t have been clearer, and more damming.

Football is about heroes and villains. From Marcus Rashford, the unofficial ‘leader of the opposition’ in Britain to Dixie Dean refusing to give a Nazi salute, to the thousands upon thousands of footballers and football fans around the world who have paid dearly, often with their lives.

The British public, as our polling shows, realise that football still has a racism problem. During the recent Euro Championships, we had an English manager and team who clearly stood at odds with the vision of England being offered by some of our political leaders.

Offered these two visions of English identity, the public sided with the players.

When the auld enemy Scotland came to Wembley and joined their English opponents in taking the knee before kick-off whilst fascists outside leafletted in defeated angst, the beginnings of this battle was evident. And as ever, this battle goes right to the heart of the establishment and wider society. Let’s not forget, the British Home Secretary had given the green light to those who wanted to boo.

As we came out of lockdown it was most evident that football would be the vehicle by which we as a country would confront the snide racism that had fermented over the last year. A period where a young Black footballer from a council estate in Manchester literally helped feed thousands of children because the government did not want to.

For many, it felt like the British government did not want a team comprising of, and driven by, such people to win.

England’s racist problem – so often exhibited by those who follow the national team – has without doubt ruined the careers of many promising Black footballers and kept away thousands of people who loved the game but just could not imagine themselves at a football ground surrounded by the kind of hatred they witness on the television and in the news.

But the power dynamic is slowly swinging back to the football fans. In 2018, 11 Premier League clubs would have still posted a profit without fans attending their games. By 2021, football faces a financial crisis – due to fans being locked out of games by the pandemic.

The opposition to the proposed European Super League shocked and terrified club bosses as angry fans organised unprecedented opposition to the project. Football fans are beginning to realise that they have the ability to make progressive change and create an environment fit for heroes and not for the haters.

We have had enough of greed; we have had enough of racism. When racists defiled the Marcus Rashford mural in Manchester, football fans from across England helped to cover up the hatred with exhibitions of the love and respect he deserves.

I hope in some way Heroes of the Terraces inspires and rewards football fans continuing to wage these battles. From small community football clubs like Clapton to the fans of Manchester United outraged enough to get a football match postponed – not by fighting and behaving like hooligans, but like the disenfranchised owners of the club they once were.

For every fan booing players taking the knee in English games, there were a dozen other fans willing to drown them out. Because through football and our new heroes – men and women with compassion and social consciences – we drive a change in wider society.

Football grounds are no longer the dumping grounds for thugs and yobs. They are now a valuable social hub almost in spite of the faceless owners that now dominate the game.

Football clubs opened their kitchens to feed people during lockdown. Everton fans demonstrated their appreciation of the actions of an opposition footballer with love. In Motherwell, the local club stepped in with warm meals for children when the schools were closed and this season are offering free season tickets to the jobless.

Football fans around the country donate to and collect for foodbanks on a regular basis and even support campaigns on the issues of depression and period poverty.

If we, the fans, cannot own the clubs, then we must and will own the environment. We have our heroes. We have our Dixie Dean, who wouldn’t salute for Hitler memories, and more recently, the England fans chanting “you’re just a bunch of racist wankers” to the far right in Bulgaria in October 2019.

Things appear bad and racist incidents are often amplified (perhaps rightly so), but I sincerely believe we are heading in the right direction.

Nobody took the knee for Vince Hilaire, Paul Canoville and the literally thousands of other Black footballers whose working and sporting lives were badly impacted by the racist abuse they received.

We have so much more to win than we have to lose in reminding ourselves that football is our game and belongs to all of us. Remind yourselves and tell others. A change is gonna come. It remains the beautiful game.

With the new football season underway, and to coincide with the launch of the new HOPE not hate Charitable Trust publication, Heroes of the Terraces, Nick Lowles looks at new polling on football and racism.

With the curtain lifting on the new football season, new polling commissioned by HOPE not hate has some powerful results which highlight the state of racism in football, and how united people are in opposing it.

Here’s the big result for me: 3 out of 4 people (72%) now recognise that racism is a serious problem in football – including 66% of Conservative voters who agreed it is ‘serious’ or ‘very serious’. The polling also revealed that:

We’re publishing these results to coincide with the launch of a new publication by HOPE not hate Charitable Trust, Heroes of the Terraces: Football, anti-fascism and protest, which celebrates how across the world, football fans have historically used the terraces to oppose fascism, racism and hate. The magazine tells the stories of people standing up to racists and offering solidarity to those targeted or using their collective strength to demand change across the world, highlighting heroes who need have stood up to hate over the last few years and across history.

While it is a sad reality that there are people who would abuse fans, teams or players, we also need to celebrate the heroes of the terraces who have been fighting racism and hate now, and over the course of history. Our polling shows that there is lots to celebrate as the success of Gareth Southgate and the England team in highlighting these issues has created a rallying cry against racism in football, and cemented people’s beliefs that more needs to be done to tackle the problem.

I hope you’ll get a copy of the new magazine, but we’ll also be publishing selected articles from it on our site.

Shaista Aziz is a journalist, writer and anti-racism campaigner. She’s also part of the FA’s Refugees and Asylum Seekers Football Network. In this article for the Heroes of the Terraces she writes about the Euros, the ugliness of the racism players faced, and the hope of the response from fans.

So that was Euro 2020 and what an emotional, exciting and powerhouse of a festival of football and goals it was – ending in the grand finale where the mighty Azzuri won the Euros at Wembley after 53 long years. Football came home to Rome!

There was high drama, silky skills, goals – lots and lots of them – and penalty shootouts galore. And, there was of course our young, gifted and representative England squad, playing as a team in synch with each other, on and off the pitch.

England dropped to their knee at the start of every game in anti-racist solidarity. Our captain, Harry Kane, wore a rainbow armband in solidarity with LGBQTI+ people and communities. Our inclusive England team won as many fans over for their solidarity and belief in equalities as they did for their football.

England defended hard and scored goals, including sinking Ukraine with four. That match was surely one of the least stressful matches England fans have ever witnessed. Oh, we also beat Germany too – for the first time in a competitive game at Wembley since 1966.

By the time Euro 2020 concluded, the ball had ended up in the back of the net 142 times in 51 matches. That’s a phenomenal goal rate and one of the highest in the history of the competition. Euro 2020 produced electrifying football, sending heart rates pulsing and in some ways made up for the long enforced shut down of the beautiful game as the Covid-19 pandemic ripped through Europe and the world, bringing the game we love and the world as we know it to a standstill.

England dropped to their knee at the start of every game in anti-racist solidarity.

Football badly needed Euro 2020, delayed by a year due to the pandemic, just as much as we the fans needed it. It followed the trauma of Covid, the loss of loved ones, lockdown isolations and the impact on our mental and physical wellbeing, our lives and communities – much of which will require processing over years to come and can’t be reversed.

Euro 2020 injected long overdue humanity and decency into football, forcing a temporary reset of the multi-billion pound capitalist global football machine that is obsessed with sponsorship and generating colossal amounts of revenue for the out of touch organisations that run football. The sight of Cristiano Ronaldo sneering at the bottles of product-placed soft drinks strategically put in front of his face at a press conference was deeply satisfying and is most likely one of the main times Cristiano, a marmite figure, united so many of us. When he lifted up the sugar laced bottle of drink to shove it out of the way, pleading on everyone to drink water instead, it was reminiscent of a mosquito being zapped. It was a glorious moment of conscious and consciousness raising disruption to add to the Euro 2020’s list.

Cristiano’s mosquito zapping move led to claims that one of the world’s biggest companies lost billions off its share price. This was later proved to be fake news.

Euro 2020 also amplified the ugliness of the beautiful game, the racism, the thuggery and violence off the pitch too.

But for now, back to what happened on the pitch during the competition. Football blog MyKhel.com number crunched the stats for Euro 2020 summing up how exciting this competition was. England feature a few times in the roll call of honour too. You blatantly know future pub quizzes and general knowledge football questions will be based on these spellbinding stats and facts for years to come.

What happened on the pitch made for headline global news as much as what happened off the pitch – with our England team forcing the nation to hold more uncomfortable conversations about racism not just here in the UK but across Europe too. England players taking the knee was described by Home Secretary Priti Patel as “gesture politics”, with so called England fans booing the national team claiming they wanted to keep politics out of football.

Booing your own side because they want to be counted as unapologetic anti-racists is not only deeply horrifying and ugly, it’s also deeply political. Football was dragged into the government’s manufactured culture wars and football came out kicking, screaming and shouting in anti-racist solidarity and won this battle. No-one is under any illusion that winning the (anti-racism) war still remains a goal.

Euro 2020 also amplified the ugliness of the beautiful game.

When England lost to Italy on penalties in the final and our three young Black players, Rashford, Sancho and Saka, missed their spot kicks, the political climate and discourse in this country further emboldened and empowered the racists into overdrive. The poisonous racist hate was over-flowing and absolutely nobody including the culture warriors and the architects could deny what was happening because, in the words of James Baldwin: “People who treat other people as less than human must not be surprised when the bread they have cast on the waters comes floating back to them, poisoned.”

The morning after the final, my two friends and I, Amna Abdullatif and Huda Jawad, England fans, football fans, and visibly Muslim women wearing hijabs and women of colour, set up a football petition calling on the government and the Football Association (FA) to work together to ban racists from football for life.

Calling ourselves #TheThreeHijabis, riffing off the Three Lions, our anti-racism campaign went viral and within 48 hours of our petition being launched 1 million+ people signed up to create an anti-racism movement. We secured blanket national media coverage and international media coverage too, including in the New York Times and the Washington Post.

Less than 72 hours after our campaign launch, Boris Johnson stood up in Parliament during Prime Ministers Questions to say the government would ban online racists from football. We welcome the Prime Minister’s commitment to doing this but as the new football season approaches, we demand action and accountability from the government, the FA, tech companies, and wider football to tackle racism in football and society. You can’t do one without the other.

This summer, along with an army of 1 million+ people, we’ve drowned out the racists and reclaimed football back from the racists and bigots. We’ve reclaimed the narrative. For football to become truly anti-racist and a game that is safe for all minorities and communities everywhere, we need to build the anti-racism movement we’ve collectively and organically started through the beautiful game.

Please join our movement by signing and sharing the petition

From Heroes of the Terraces, we take a look at how Ultra culture turned fascist, and what fans are doing to try and turn the tide.

Whether Elseid Hysaj understood the significance of Bella Ciao when he stood up in front of his new Lazio teammates to sing it is unclear. Perhaps the Albanian international sung it because he had heard it in the Netflix show Money Heist and it was the only Italian song he knew.

Or perhaps he did secretly know that the song is the anthem of the partisans who fought Benito Mussolini’s regime in the 1940s and has been adopted by the left as their own.

The reason Hysaj sang Bella Ciao on his arrival at the club quickly became immaterial. He sang it and that was enough for the Lazio Ultras, a hardcore fan group that congregate on the Curva Nord (North End) of the Olympic stadium.

The Ultras flew a banner from a prominent bridge in central Rome which simply read: ‘Hysaj is a worm, Lazio is fascist.’

This was followed up by one of their leaders, Franco ‘Franchino’ Costantino, telling the Adnkronos news agency “Historically, our fans have always been to the extreme right, and I say that with pride. Someone singing ‘Bella Ciao’ with a Lazio jersey on is just completely insane. Hysaj was wrong, there are no excuses.”

Lazio has one of the most notorious fascist followings of any team in Europe, caused by drawing much of its fan base from the Rome suburbs and the connected countryside – areas of strong support for Benito Mussolini back in the 1920s and 1930s.

In more recent years, the fascist leanings of Lazio’s supporter base has come through its Ultra groups, and most famously of all the Irriducubili, (the Die Hards).

Formed in 1987, the Irriducubili quickly earned an unenviable reputation for violence, choreography and fascist politics. Right-armed fascist salutes, antisemitic banners and monkey chants at opposing black players became the norm.

After the Serbian paramilitary leader Željko Ražnatović, better known as Arkan (see page 111) was murdered, the Irriducubili hoisted up a banner which read: ‘Honour to the Tiger, Arkan’. The demonising of arch rivals Roma as a Jewish club with chants of “Auschwitz is your country, the gas chambers are your home”. The banning of fans from the stadium in January 2020 after just the latest incident of Lazio fans racially abusing opposing black players.

For most football supporters who have come across the Lazio Ultras during European cup competitions, the enduring memory is one of violence, particularly when they have played matches in Rome. And all too often, knives are the weapons of choice.

For most of its existence, the Irriducubili was led by Fabrizio Piscitelli, who operated by the name Diabolik. Piscitelli was 21 years old when the Irriducubili was formed, but it was not long before he was a leading figure in the group.

“I grew up in a red neighbourhood and directly across the street in front of me was the head of [Roma’s Ultra group] the Fedayn,” Piscitelli was to tell James Montague, who went on to write the excellent 1312: Among the Ultras. “He was a far-left activist and I grew up the opposite, far-right Lazio. That was a response to Roma being a leftist team in a leftist neighbourhood and Lazio having some of these fighters who were of the far right.”

Under Piscitelli’s leadership, the Irriducubili became even more violent and political. Like many other Ultra groups, they also had amazing power over the club. When Beppe Signore, a Lazio forward who was adored by the Ultras, almost signed for Parma in 1995, thousands of the Irriducubili rioted. Any prospect of Signore leaving the club were quickly ended.

When hundreds of Irriducubili turned up at the clubs training ground after a heavy defeat to arch-rivals Roma, the club captain, Alessandro Nesta, pulled Piscitelli aside for a chat and a formal meeting was agreed between players and Ultras.

Piscitelli’s reign as Irriducubili boss finally ran out in 2019 when he was gunned down on a park bench in Rome in what is was believed to be a feud with a rival drug gang. To mark his death, the Irriducubili Ultras put on a special display for their fallen leader.

The Ultras emerged in Italian football in the 1950s with the emergence of the Fedelissimi Granata of Torino, but it was in the late 1960s that the modern Ultra groups really began to take hold in Italian football, with the formation of groups like the Fossi del Leoni of AC Milan and Boys San of their bitter rivals Inter.

The term ‘ultra’ was first used by Sampdoria’s Ultras Tito Cucchiaroni with an acronym of Uniti Legneremo Tutti I Rossoblu A Sangue (“all together we will beat the rossoblu fans to blood”). Other existing gangs soon changed their names to incorporate the word ‘ultras’ in their names, so, in 1970, Fedelissimi Granata became known as Ultras Granata.

S.S. Lazio Ultras, a forerunner to the Irriducubili, emerged in 1974 – in the team’s championship winning season – and it too already aligned itself to fascist imagery, chants and behaviour.

Early Ultra culture was a youth reaction to Italy’s sedate supporters’ clubs and went to stand, and sing, behind the goal in much the same way as punk and skinhead culture in the UK.

“At its foundation,” the sports writer Tobias Jones has asserted, “the movement were largely far left, with names inspired by global partisan struggles. Petty criminals and political extremists were drawn to the terraces’ carnival atmosphere and the huge consumer base.”

The Ultra movement was quite different from the British hooligan counterparts. While the former admired and even adopted some of the aggressive and violent characteristics of British hooligans, there were many obvious differences. While the British hooligans avoided wearing colours, the Italian Ultras wore them with pride. Inside the stadiums, the hooligan hardcore moved from the ends, normally behind the goals, to the more expensive seats in an attempt to avoid police scrutiny and show off their wealth. By contrast, the Ultras took over the ends, or ‘curves’ as they are known in Italy, and put on well-rehearsed displays and songs. Banners and flags were often hand-painted, and for big games often planned well in advance.

To the Ultras, these stadium displays were to demonstrate support for their team and to intimidate their rivals.

The Ultras were to become an integral part of the Italian game, often controlling certain gates at grounds so only supporters of their group would gain entry and sometimes even being consulted on key club developments.

It was the Ultras who organised the travel for thousands of Milan fans to get to the 1994 European Cup final in Athens, where the Italian team beat Barcelona. The club did not organise any travel itself.

The birth of the Ultra movement coincided with the surge of political violence and terrorism in Italy. From the left there were the Red Brigades, who kidnapped and murdered former prime minister Aldo Moro in 1978. From the far right, there was the Nuclei Armati Rivoluzionari, who in 1980, planted a bomb outside Bologna railway station which killed 85 people and injured over 200 others.

Italy’s political turmoil in the country spilled over into the rest of the society, including the football terraces, as rival fan groups adopted the names, slogans and even images of the terrorist groups they most identified with.

Many AC Milan fans identified with left-wing politics and in 1975 the Brigate Rossonere was formed, with many followers wearing berets and face scarfs to replicate the imagery of the Red Brigades and Latin American communist guerrillas. A flag of of Che Guevara would regularly fly in Curve Sud, AC Milan’s home end, until the mid-1990s.

Other left-wing Ultra groups emerged at Roma, Bologna, Sampdoria and Livorno.

There were others who, like Lazio, identified with the far right. Among them were Inter Milan, Juventus and Verona.

However, political allegiances shifted over time, with some previously left-wing Ultra groups becoming apolitical and others, like Roma, becoming increasingly right wing. While there has never been complete political hegemony within each fan base, there has been a significant shift to the right of the main Ultra groups.

“Fascism seemed perfectly aligned with an “ultra” form of fandom, which delighted in paramilitary uniforms and violence,” says Tobias Jones.

“The worldviews were also comparable: partisan fans have a simple, Manichean worldview of them-and-us in which hatred of outsiders is normalised. The stadium is a setting for warfare, where territory is defended and conquered. Inevitably, as happened this week, martyrs fall and – as in fascism – death is thus fetishised, almost yearned for. In that bleak world, words like “tolerance” and “multiculturalism” have absolutely no meaning.”

The dominance of fascist support within Italian Ultra groups has coincided with declining crowds, partly driven by rising violence and soaring costs. Hooligans, racists and fascists are driving ordinary supporters away and by doing so reinforcing their dominance.

As one Lazio fan succinctly put it after the death of the Irriducubili leader. “Piscitelli ruined the image of Lazio in the world. Lazio now implies racism, fascism and collusion with the Camorra. His was a rabble of criminals.”

Lazio’s pro-fascist reputation is being challenged by a group of fans who have joined together to form “Laziale and Anti-Fascist” (LAF).

Established in 2011 (LAF) aims to “destroy the stereotype of the Fascist Laziale in Italy and throughout the world.”

LAF claims several thousand followers, several hundred active members, and says it pursues a two-fold aim: “to erase from the name of Lazio any infamous political label” and “to prevent neo-fascist movements from continuing to use the Curva Nord (North Stand) from indoctrinating young people who have entered the stadium only to support Lazio”.

Tom Williams on the French defender who led the way in battling racism in French football.

It was during a fateful friendly match between the national teams of France and Algeria in October 2001 that Lilian Thuram (who would go on to become the most capped player in France) gave the world its first indication that he possessed a more keenly developed sense of social justice than the average footballer.

The highly charged fixture, the first between the teams since Algeria gained independence from France in 1962, took place less than a month after the September 11 terror attacks in the United States. Before kick-off at the Stade de France in the northern Paris suburb of Saint-Denis, the French national anthem La Marseillaise was loudly jeered by the thousands of Algeria supporters. With 12 minutes of the match remaining, and France leading 4-1, the tension finally told when dozens of spectators flooded onto the pitch, causing the game to be abandoned.

“With everything that’s happening in the world today, with the hope that these two countries had to get closer to each other…” he fumed afterwards. “And then he, and the others, screwed everything up.”

As players from both sides scurried for the sanctuary of the tunnel, television pictures captured French defender Thuram angrily remonstrating with a young black pitch invader dressed in a grey pullover and beige trousers who had gaily charged onto the playing surface with a group of friends. But Thuram was not simply annoyed that the match had been interrupted. He was worried about the message that would be sent to the wider world.

Seven years later, French football magazine So Foot reunited Thuram with the pitch invader, a second-generation Senegalese immigrant called Mamadou Ndiaye, who had been 17 when they fleetingly met on the Stade de France pitch. So what exactly had Thuram said to him, Ndiaye was asked. He remembered Thuram’s words clearly:

“What you’re doing is wrong! You’re showing a bad image of yourself to the racists, to the people watching on TV. They’ll be very happy to have another stick to hit you with. Do you realise what you’re doing?”

Thuram’s strong sense of right and wrong has not diminished over the two decades since that night, and he has not stopped asking provocative questions.

When he retired as a player in 2008, Thuram’s footballing legacy was secure. He was one of the iconic members of the France team that had won the country’s first World Cup on home soil in 1998, notably scoring the two goals against Croatia in the semi-finals (the only goals of his record-breaking 142-cap international career) that had taken Les Bleus into the final.

He had also won the European Championship with France in 2000, had reached a second World Cup final in 2006 and had represented leading European clubs Monaco, Parma, Juventus and Barcelona with distinction. But he wasn’t finished with achieving.

Known by the slogan black-blanc-beur (‘black-white-Arab’), France’s 1998 World Cup winners shared roots that stretched to all four corners of the country’s former colonial empire. Star player Zinédine Zidane, scorer of two goals headed in during the final against Brazil, was born in France to parents from Algeria. Midfielder Patrick Vieira was born in the Senegalese capital Dakar, while centre-back Marcel Desailly came from the Ghanaian capital Accra.

There were also players with roots in French Guiana, New Caledonia and the French Antilles. The team’s triumph and the huge countrywide celebrations it prompted seemed to offer the possibility of a new era of inter-racial harmony, but the events of the following years – from the 2005 riots in the suburbs of several French cities to troubling political gains by France’s far right – exposed the naivety of that hope.

Thuram set up his own foundation in 2008 – the Lilian Thuram Foundation – in order to educate people about racism, and he has devoted his life to the cause ever since, touring France and the world to speak at schools, colleges and conferences about the dangers of allowing discriminatory attitudes to go unchallenged. He has written books, curated exhibitions and worked with an endless list of French government agencies and non-profit organisations. A UNICEF goodwill ambassador, he was made an Officer of the Legion of Honour – one of France’s highest civilian honours – in 2013.

Thuram first encountered racism as a child after leaving his native Guadeloupe in September 1981 to join his mother, Mariana, who had moved to mainland France a year earlier to work as a cleaning lady. Thuram was nine-years-old when he and his brothers and sisters arrived in France from their Caribbean home and his early experiences in the school classroom cut him to the core.

“What struck me when I arrived was that some of my classmates judged me because of my skin colour,” he told British football journalist Matthew Spiro in the book Sacré Bleu. “They made me believe my skin colour was inferior to theirs and that being white was better. These were nine-year-old kids. They weren’t born racist, but they’d already developed a superiority complex. From that moment I started to ask myself questions: ‘Why are they teasing me? Where does this come from?’ My mother couldn’t provide me with answers. For her this was just the way it was. There are racists and it won’t change.” He has described his campaigning as a way of trying to make sure that “other children don’t suffer the same thing”.

The fact that Thuram remains a powerful voice within French football is both a sign of his tireless commitment to racial justice and an indication that black and minority ethnic players continue to experience the same discrimination to which he was first subjected in the early 1980s. In April 2019, Amiens captain Prince Gouano was targeted by monkey chants from a rival supporter during a French league game against Dijon. In September 2020, a stormy fixture between arch rivals Paris Saint-Germain and Marseille culminated in accusations of racism against both sides, but no sanctions were issued.

Meanwhile, earlier this year Saint-Étienne forward Denis Bouanga and Nantes midfielder Imran Louza spoke out about the pain they had felt after receiving racist messages on social media. And yet, remarkably, in a television interview last autumn, Noël Le Graët, the long-serving 79-year-old president of the French Football Federation, declared that “racism in football doesn’t exist or barely exists”. His remarks were met with stupor in France and Thuram was quick to respond.

“Noël Le Graët is anything but naïve,” he said during an interview with Québécois radio station QUB Radio. “He’s coming from a standpoint where he’s the president of the federation and he wants to protect football. But when I love someone, I prefer to tell the truth.

“I love football, but there is racism in French football. And it’s the racism that there is in French society. We can always deceive ourselves and lie to ourselves: [but] we live in societies where, depending on the colour of your skin, you don’t experience the public space in the same way.”

Thuram’s uncompromising approach has occasionally put noses out of joint. His former France team-mate Christophe Dugarry, a fellow member of the 1998 World Cup squad, once told him to “stop giving everyone lessons”. After Thuram criticised Patrice Evra over his role in the off-pitch turmoil that plagued France’s campaign at the 2010 World Cup in South Africa, the former Manchester United defender accused him of behaving as if he was Malcolm X. But if older players have occasionally exhibited wariness – if not outright hostility – towards Thuram’s activism, the willingness of present-day footballers such as Marcus Rashford and Raheem Sterling to publicly call out racism suggests that the sport is finally coming round to his way of thinking.

Thuram has two sons, Marcus (named after the Jamaican civil rights leader Marcus Garvey) and Khéphren, both of whom are professional footballers. Last year, in a sign that the apple did not fall far from the tree, Marcus Thuram became the first high-profile footballer to take a knee following the killing of George Floyd, adopting the pose after scoring for Borussia Mönchengladbach in a German league match against Union Berlin. “Together is how we move forward,” Thuram Jnr wrote on Instagram beneath a photograph of himself kneeling, head bowed, on the Borussia-Park turf. “Together is how we make a change.”

The gesture, which echoed NFL player Colin Kaepernick’s protests against racism and police brutality in the United States, has since been taken up by footballers around the world, not least in the globally popular English Premier League, where players dropped to one knee before kick-off in all 380 games of the 2020-21 season.

Forty years after he first encountered racism in a French classroom, 20 years after his run-in with the Stade de France pitch invader, Lilian Thuram’s message is resonating more loudly than ever.

The segregation of Roma people is blatant in many areas of life across the European continent, including schooling, housing, work and healthcare. So too in football.

“Bulgaria and racism. The two go hand-in-hand,” Steffan Stefanov told The Guardian two days after England’s players suffered racial abuse from Bulgarian fans during the Euro2020 qualifier in Sofia, back in October 2019.

“It’s our reality, we live it every day,” said Stefanov, a Roma tax driver in Bulgaria’s capital city. “I’m sorry for the England players who were targeted but, in truth, this was pretty minor for us.”

While racist abuse of players attracts great attention – as it has recently done in England after the Euro 2020 finals – within countries such as Bulgaria it is the Roma who are the principal targets, even though they make up just under 5% of the population.

The segregation of Roma people is blatant in many areas of life across the European continent, including schooling, housing, work and healthcare.

In sport, anti-Roma discrimination and segregation is also strong. There have been numerous anti-Roma incidents in professional football, perpetrated by players and managers, as well as anti-Roma hatred fomented by “ultra” supporters and discrimination at amateur level. Romaaccess to sport is below average in many countries, too.

In Slovakia, a report published in 2011 by the Institute for Sociology of the Slovak Academy of SciencesBratislava, revealed that Roma households lack resources to pursue sport and recreational activities.

Combined with often poor public transport and problems getting to school excluded most Roma children from leisure activities, it said at the time.

In Spain, where it is estimated that between 1-2% of the total population is Roma, 2013 figures showed that 72% of the Roma population lived in a situation of exclusion.

Like in Slovakia, Roma youth in Spain and Portugal face similar challenges that have a negative impact on their participation in sport.

The lack of local clubs in rural areas and poorer neighbourhoods, where the Roma often live, and the lack of sport programmes targeting Roma children and youth, add to their economic and cultural challenges.

To counter that, a Barcelona-based Roma organisation, Federació d’Associacions Gitanes de Catalunya (FAGiC),has worked with Roma children across the region through an education and football programme, using the sport to encourage school attendance and good behaviour.

“FAGiC knows that football is very important to Roma children and we know that they can’t play because of external factors, so we created a project where children can practise sport as a reward if they commit to go to school and study,” said Annabel Carbello from FAGiC.

“It is estimated that 10-12 million people living in Europe are Roma. As Europe’s largest minority group, their representation across football should be equally visible,” added the Fare network, an umbrella organisation that brings together individuals and organisations to combat inequality in football and usessport as a means for social change.

“Football’s empowering qualities and inclusive values go beyond the playing field and are propelled across all areas of life. Football, as the most popular sport in the world, should be accessible to all.”Across Europe, of course, the Roma have suffered tremendous prejudice.

In Bulgaria, three right-wing populist parties have ruled in coalition as the “United Patriots”. One of the three, theBulgarian National Movement, has a manifesto calling for the creation of “reservations” for Roma, based on the model used for Native Americans, claiming that they could become “tourist attractions”.

Following violence between Bulgarian Roma and non-Roma in 2019, the party’s leader (and deputy prime minister) Krasimir Karakachanov said: “The truth is that we need to undertake a complete programme for a solution to the Gypsy problem. His predecessor as deputy prime minister, Valeri Simeonov, had described the Roma as “arrogant, presumptuous and ferocious humanoids”. He was also chair of Bulgaria’s National Council for Cooperation on Ethnic integration Issues at the time.

Roma have also been targeted in Italy, France, Hungary, Romania and elsewhere on the streets of Europe. At matches, such as a game between Steaua Bucharest and rapid Bucharest in 2012, Steaua’s fans shouted chants against Roma including: “We have always hated and will always hate the Gypsies” and “Death to the Gypsies”. The Rapid Bucharest stadium is situated in the popular Giulesti neighbourhood, where many Roma live.

Roma women have also been abused by football fans on the streets of Madrid, Barcelona and Rome, leading to condemnation from Milena Santerini, the General Rapporteur against Racism and Intolerance for the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE). “They have been humiliated, taunted and even urinated upon by some supporters, as others watch on, cheering. These acts are demeaning and deny human dignity. They cannot be accepted.”

Jonathan Lee, spokesman for the European Roma Rights Centre, said at the time of the abuse directed at England in Bulgaria in October 2019: “Unfortunately, racist chanting and offensive gestures from the terraces is not even close to as bad as it gets in Bulgaria. Last Monday night, Europewas confronted with what for most Roma in the country is the everyday. Rising anti-Gypsyism, decline of the rule of law, and increasingly fascist political rhetoric is nothing new– it just rarely gets such a public stage.”

Lee added: “This is an EU member state where violentrace mobs are the norm, police violence is sudden and unpredictable, punitive demolitions of people’s homes are the appropriate government response, random murders of Romany citizens only a fleeting headline, and the rights and dignity of Romany citizens are routinely denied on a daily basis.”

In 1895 Rabbi Howell made history as the first Romany footballer to play for England. Throughout his career Howell Was known in the newspapers as “The Gypsy”, a nickname Steven Kay, who has written a book on Howell, said Howell would play up to, often saying he lived in a caravan in the woods.

But, he said: “He was just pulling their leg. He just let them think what they wanted to think.”Howell’s international career may have been limited by his background (he was only capped twice), but it is unclear whether he was subject to any abuse because of his Romany roots.

Portugal striker Ricardo Quaresma – also known as ‘The Gypsy’ – has told Portuguese newspaper O Jogothat racism was rife in the country.

He said: “When I hear people say there is no racism nowadays it makes me laugh. When something happens in Portugal it’s always the fault of gypsies, blacks, immigrants. It’s tough to live with this.”

Quaresma is one of a number of high-profile players of Romany descent, including Eric Cantona, Andrea Pirlo, Hristo Stoichkov, and former Southend United and Coventry City player Freddy Eastwood. There are many others who have played across the European continent.

However, their achievements appear to have done little to stop the abuse directed at players with Roma heritage.

Right-wing comic Kearse saves the worst material for his anonymous Telegram account HOPE not hate has identified an anonymised Telegram account belonging to the GB…