HOPE not hate uses cookies to collect information and give you a more personalised experience on our site. You can find more information in our privacy policy. To agree to this, please click accept.

On 18 December 2021, just days after MPs voted to pass a new set of COVID-related restrictions, Piers Corbyn, brother of the former Labour leader Jeremy, told a crowd of several hundred gathered outside Downing Street that they needed to “get a bit more physical” with “lying MPs”.

Corbyn, the face of the UK’s conspiracy theory-driven, anti-vaccine protest movement, told his followers that they need to:

“…hammer to death those scum who have decided to go ahead with introducing new fascism […] We’ve got to get a list of them […] and if your MP is one of them, go to their offices and, well, I would recommend burning them down, OK. But I can’t say that on air.”

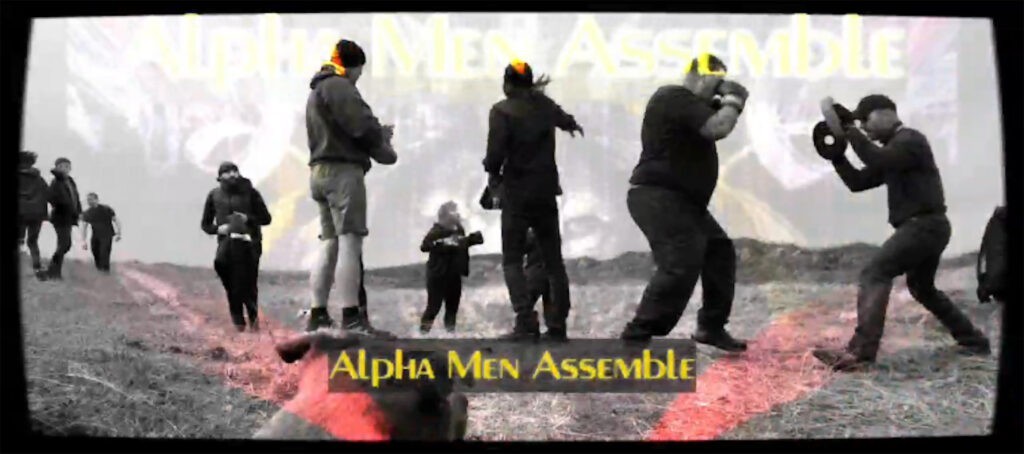

The following month, a group of roughly 200 people met in a park near Walsall, Staffordshire, under the banner of “Alpha Men Assemble”, and underwent combat drills overseen by Danny Glass, a former soldier in the Royal Fusiliers. According to an undercover reporter for the Daily Mail, under the watchful eye of the police the organisers presented themselves as a law-abiding, non-violent group, but when out of earshot Glass stated his intent to “take it to the Old Bill”, with another organiser discussing “hit[ting] vaccine centres, schools, head teachers, colleges, councillors and directors of public health in every area”. Figures associated with the group were present when an angry mob hurled abuse at Labour leader Keir Starmer at a protest near Parliament in February.

Around the globe, the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing government counter-measures have catalysed the spread of numerous conspiracy theories, disseminated by a constellation of organisations, campaigns, outlets, online spaces and individuals. These networks have generated an outpouring of false information, variously linking COVID-19 to the rollout of 5G technology, a Chinese bioweapon or denying the existence of the disease altogether, alleging it to be a smokescreen for totalitarian controls and the microchipping/poisoning of the population via vaccines.

In the UK, the spread of such notions has given rise to a prolific protest movement, with hundreds of demonstrations across the country, some of which brought upwards of 10,000 people onto the streets of London. This broad coalition is loose, multifaceted and fluctuating, consisting of individuals from across the political spectrum and stretching from the edges of the mainstream to the political extremes. Many followers are unaligned to any clearly delineated ideology or organisation, but share a populist worldview and an outsider identity that positions them as heroic “truth seekers”, standing together against a sinister elite.

As 2021 progressed, sections of this broad coalition became increasingly radical and aggressive. After two years of energetic protest with no tangible impact on policy, an increasing sense of frustration has fed into a confrontational ethos, the normalisation of violent language and the emergence of new, militant groups that have vowed to prepare for a “global war against governments”, posing a threat not just to public health but also to political and social cohesion.

There are numerous drivers behind the increasing radicalisation. With lockdown restrictions easing and widespread vaccine success, those still passionately involved in the scene are a shrinking but increasingly radical rump. Many of those who remain have progressed far enough down the ‘rabbit hole’ into believing in ‘superconspiracies’, which bundle multiple conspiracy theories together into a grand overarching conspiratorial narrative.

For many in this scene, the pandemic has ‘revealed’ the existence of a pernicious, or even all-powerful, group of conspirators pulling the strings behind world events and seeking to control society. The danger here is that, in the eyes of some believers, combatting this grand conspiracy requires more drastic action. It is no longer merely about campaigning to lift lockdown regulations, but about fighting an all-powerful oppressor, which, in their eyes, makes more extreme behaviour and tactics admissible.

The radicalisation of sections of the anti-vaccine milieu stems, in part, from its toxic online environment. Over the past 18 months, sweeping bans from mainstream platforms have forced or encouraged the conspiratorial networks that flourished during the pandemic to migrate to alternatives, such as the video hosting sites BitChute and Odysee, the Twitter clone Gab and the messaging app Telegram.

The latter platform in particular has become central to the organisation and propagandising of the UK’s conspiratorial milieu, providing anonymity and protected messaging but also enabling the extensive spread of content. Telegram hosts countless public channels and private chat groups that promote various conspiracy theories, ideologies and campaigns, many of which are locally focused.

For example, in January 2021, a UK “Great Reopening” campaign emerged that urged businesses to break lockdown rules by opening their doors. It was organised via dozens of coordinated regional Telegram groups that quickly gained thousands of members. While the campaign itself was a failure, the groups continue to function as hubs for sharing propaganda and promoting local and national actions.

Even though this online isolation inhibits the spread of toxic ideas to new audiences, one side effect is that it has further detached conspiratorial communities from mainstream views and values, paving the way for further polarisation. As we have documented elsewhere, platforms such as Telegram and Gab are also home to pre-existing, entrenched extremist subcultures, some of which advocate for political violence. Trapped in bubbles practically free from moderation and in close proximity to a variety of extremists, the risk of cross-pollination with other extreme belief systems has intensified, including antisemitism and sovereign citizen-style beliefs.

On platforms such as Telegram, an intense hostility has built towards those deemed responsible for the crisis, often dehumanised in extreme terms. Figures active in political, media and health institutions are frequently portrayed as cannibalistic Satanists, supernatural puppeteers and even literal demons, often with special predilection for abusing/enslaving/murdering children. Such highly emotive narratives raise the stakes of their struggle to a kind of spiritual war between Good and Evil, thereby (supposedly) justifying promises of violent retaliation.

For example, one noticeable theme in many such online spaces is that of a coming “day of judgement”, often in the form of a Nuremberg-style trial and the subsequent execution of perceived perpetrators. “They stole two years from the entire planet and mandated a lethal injection, the people on tv need to hang…” wrote one member of a Birmingham-based Telegram group. Another told fellow members of a British group:

“Yiu [sic] need to go after the killers, the killers are Uk gov, USA and Australian governments, the homes and offices of all persons involved in this Genocide must be surround, and the perpetrators dragged out into street, stripped and trial on the spot, and hanged from lamposts”.

While violent language does not necessarily lead to violent action, the endorsement of violence is a significant advance in the course of radicalisation. In extreme cases, it can result in action. Recent exploratory studies have highlighted points of intersection between conspiracy thinking and violent extremism: for example, Abdul Basit has argued that both phenomena tend to be rooted in desires to overcome feelings of powerlessness, a deep distrust of government institutions, political infrastructure and mainstream narratives, and a polarised “us versus them” worldview.

In Basit’s view, while “establishing a direct causal-link” between conspiracy theories and violent extremism is difficult, “the former’s role as enabler, multiplier and facilitator of the latter is undeniable”. A recent study by Frederico Vegetti and Levente Littvay, based on US survey data, observed that those more prone to conspiracy beliefs are also more likely to endorse political violence, arguing that conspiratorial narratives “help people channel their feelings of resentment towards political targets”, thereby “fuelling radical attitudes”.

Such observations are particularly concerning as fantasising about bloody retribution has spilled into the offline arena. For example, on 24 July last year thousands gathered in London’s Trafalgar Square for a rally compèred by former (struck-off) nurse Kate Shemirani, who called for the collection of the personal data of NHS staff. She went on to state:

“At the Nuremberg trials, the doctors and nurses stood trial and they hung. If you are a doctor or a nurse, now is the time to get off that bus. Get off it and stand with us, the people, all around the world they are rising”.

On 20 October, a week after the murder of Sir David Amess MP, Piers Corbyn was among a small group of protesters who erected a gallows in Parliament Square.

Radicalisation stems, in part, from a loss of faith in traditional channels of participation. While numerous anti-vaccine activists stood for office last year, disappointing results may have exacerbated an existing disillusionment with the electoral system.

For example, Piers Corbyn ran for London Mayor in May but came 11th, with just 0.8% of the vote. The newly-founded Freedom Alliance, which claimed to be “the political arm/ wing of the freedom community”, stood over 100 candidates in various elections last year, but failed to win a single seat. David Kurten, a former leading UKIP member and current leader of the conspiratorial Heritage Party, similarly yielded dismal results. The consistent battering received by more mainstream lockdown-sceptic groups, such as Reform UK, suggests that campaigning politically against COVID measures simply does not garner support. For some prone to conspiracy thinking, this has confirmed suspicions that the system is rigged and more contentious means must be pursued.

By the beginning of 2021, the weekly street protests held around the country were also yielding diminishing returns. While huge demonstrations in London over the past two years have boosted the morale of the wider protest movement, many demonstrations outside the capital had small turnouts, with crowds sometimes outnumbered by police. Regular street demonstrations did continue across the UK, but the broad protest movement diversified its activism as well, with some contingents escalating forms of “direct action” as the year progressed.

One such tactic was to aggressively and directly confront supposed culprits. For example, during the summer a network organised on Telegram (under the name “Official Voice”) targeted the offices of media outlets; in August, ugly clashes with police ensued after activists attempted to storm the White City building in London that was previously home to the BBC. A fortnight later, a group pushed into the central London office of ITN Productions, engaging in heated confrontations with the police and hurling abuse at Channel 4 News anchor Jon Snow, who was labelled a “fucking rat cunt” and a “paedophile”.

Activists also clashed with police outside the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency headquarters in September, leaving four officers injured. In December, Piers Corbyn was present at a demonstration in Milton Keynes that ended with the storming of a test-and-trace centre, where staff were abused and equipment was stolen.

Others in this movement have sought to intimidate perceived enemies at their homes, delivering “notices of liability for harm and death” to politicians, journalists and celebrities who have publicly supported vaccines. These actions are in part inspired by “sovereign citizen” ideology: the notion that people – not judges, juries, law enforcement or elected officials – should decide which laws to obey and which to ignore. For example, in October a group of several dozen people visited the home of the television doctor Hilary Jones, with one activist telling him “we will be here for you, you will have nowhere to hide”.

Another notable development is the emergence of militant anti-vaccine networks that view street demonstrations as ineffective, and thus promise more radical action. Foremost among them is Alpha Men Assemble/Alpha Team Assemble, a group that, as outlined in a subsequent article in this report, is attempting to establish a hardcore of activists and has attracted the involvement of a number of far-right individuals, with potentially dangerous outcomes.

It is impossible to know when conspiracy theorists will act upon their beliefs. Acts of criminality cannot be taken as representative of a diffuse milieu numbering many thousands of people. However, there is a very real risk that acts of vigilante violence, whether coordinated or unplanned, by groups or lone actors, could stem from the fringes of the scene in coming months.

In September 2020, Gilles Kerchove, the EU’s counterterrorism chief, expressed his concerns that “new forms” of conspiracy-theory driven terrorism would emerge in the wake of the pandemic. Sadly, it appears as though such fears are warranted. In December last year, German police uncovered an alleged plot to assassinate the governor of Saxony by an anti-vaccine group communicating on Telegram. In January this year, a conspiracy theorist was jailed after brandishing a flaming torch and livestreaming himself shouting outside the home of the former Dutch foreign minister; the same week, one of Italy’s foremost immunology experts was sent a bullet alongside a letter threatening her family.

UK authorities are cognisant of such dangers, but face new challenges. As Milo Comerford of the Institute of Strategic Dialogue told The Guardian, traditional counter-extremism approaches are “geared towards threats from organised groups with clear political objectives”. The amorphous, post-organisational nature of the anti-vaccine movement means it is harder to monitor and predict, despite the abundant anger that is fostering.

As lockdown measures become a thing of the past, the UK’s conspiracy theory-driven protest movement may contract, but it will not simply disappear. New networks have formed and thrived, and many activists will not readily relinquish the causes to which they have given considerable investment, and potentially lost friendships, relationships and jobs to support. The economic and social fallout of the pandemic will continue for years yet, and experience has shown that anxieties induced by economic hardship can be exploited by extremist actors. The result may be a scene that is smaller but more volatile, and primed for disruption, harassment and even violence.

Download the full report below.

A Reform Party candidate fantasised about deporting “millions” of British citizens to “rid itself of the foreign plague we have been diseased with”. UPDATE: Reform…