HOPE not hate uses cookies to collect information and give you a more personalised experience on our site. You can find more information in our privacy policy. To agree to this, please click accept.

In November 1997, 20 years ago this month, the Runnymede Trust published Islamophobia: A Challenge for Us All. The report, though contentious, was widely recognised…

In November 1997, 20 years ago this month, the Runnymede Trust published Islamophobia: A Challenge for Us All. The report, though contentious, was widely recognised as an important step towards anti-Muslim prejudice being more thoroughly researched, better understood and taken more seriously in the UK.

Twenty years on much has changed; sometimes for the better yet, sadly, sometimes for the worse. As the Runnymede Trust pointed out this year, British Muslims still have higher poverty rates, including both child poverty and in-work poverty, and the highest rates of unemployment, while hate crimes against Muslims have “undoubtedly risen in the past twenty years”.

In many ways, the world now is unrecognisable to 1997. While prejudice, racism, discrimination and hatred are constants sadly unbowed by time and progress elsewhere, the nature of modern Islamophobia has shifted and can be split into pre- and post-September 11 2001.

While those towers collapsed in Manhattan, the seismic vibrations have been and continue to be felt all over the world. The tragic images were forever burned into our collective conscience and for many still loom large over their perception of Islam and Muslims in the West.

Since then, the wars and occupations in Afghanistan and Iraq, the 2004 Madrid train bombings, the 7/7 attacks in London, the rise of the Islamic State, the 2015 migrant crisis and the wave of terrorist attacks in France, Belgium, Germany, Britain and Spain over the last few years have all impacted Islamophobia in Europe and North America.

Racism and anti-Muslim prejudice predate all these events and would continue to exist even if they had never happened, but we have to understand their unquestionable impact.

The shameful notion of collective responsibility, exacerbated by elements of an irresponsible and prejudiced press, has meant that such major world events have tangible and often terrifying repercussions for ordinary Muslims on the streets of towns and cities across the West.

HOPE not hate has been challenging anti-Muslim prejudice since we were first founded. However, it was in 2012 that we produced our first Counter-Jihad Report.

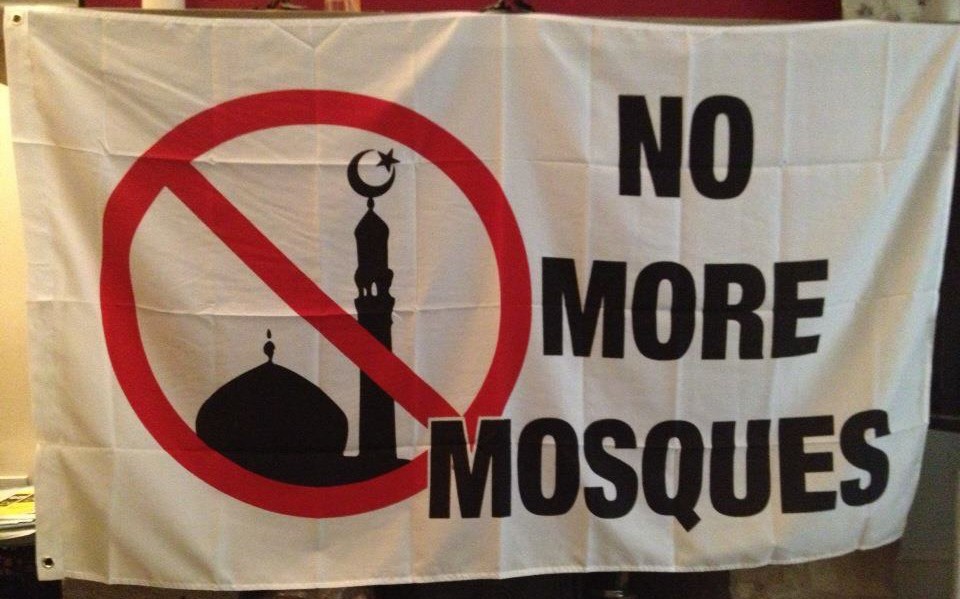

This was an important exploration into an under-researched area, namely the so-called ‘counter-jihad’ movement and the emergent conspiratorial ideology that drove it forward.

Since then we have published numerous updates to that report, launched a Counter-Jihad Monitoring Unit which constantly monitors organised anti-Muslim individuals and organisations internationally, and published numerous related reports such as Going Mainstream: The mainstreaming of anti-Muslim prejudice in Europe and North America, earlier this year.

Of course, the organised counter-jihad movement that emerged in the wake of 9/11 no longer exists in its traditional form. Many of the international organisations that sprang up and sought to spread Islamophobia internationally have become inactive.

The move towards a unified network never really materialised, meanwhile many of the attempts to create transnational anti-Muslim street movements also failed to gain traction.

However, the individuals involved in these movements are still around. Most continue to be active and many now have much larger online audiences than we would have thought possible back in 2012.

The anti-Muslim movement has become adept at successfully exploiting social media and the online world for propagating Islamophobia.

We’ve also seen increasing convergence between these actors and new movements such as the alt-light (obsessed by the superiority of the West and the supposed threat of Islam) – as typified by people like Milo Yiannopolous and media outlets like Rebel Media.

Moreover, one of the most troubling developments since we started monitoring Islamophobia more closely is the shift of anti-Muslim narratives originally confined to explicit anti-Muslim groups into mainstream political debate.

Whether this is people like Orban in Hungary, Zeman in the Czech Republic, Trump in America, or the toxic anti-Muslim rhetoric seen during the Brexit debate, Islamophobia is increasingly the norm across the European political mainstream.

Indeed, if you want to hear about conspiratorial notions of Muslim invasions of the West, no longer do you have to follow obscure anti-Muslim blogs or attend a rally of the English Defence League, instead you can listen to speeches in the parliaments of Europe.

When the Runnymede Trust published its 1997 Report it was in some ways unique. Thankfully now far more research has been done into the causes, effects and nature of Islamophobia.

To mention just a fraction, there is now the annual extensive European Islamophobia Report, the last of which included reports from 27 countries across the continent.

Here in the UK there are organisations such as Tell MAMA that track anti-Muslim hate crimes and support victims, while the Runnymede Trust has published a very useful anniversary report, Islamophobia: Still a challenge for us all.

There is also an ever-expanding community of international scholars producing invaluable research on the topic, not least the Islamophobia Studies Journal and the Islamophobia Research and Documentation Project hosted at the University of California Berkeley.

Over the coming weeks, we will be releasing our most recent work on the issue of Islamophobia and its causes.

Today, we are releasing a long essay drawing on data from our annual Fear and HOPE survey that tracks attitudes towards race, faith and belonging in relation to degrees of economic optimism and pessimism.

Combining this survey (one of the most comprehensive studies of its kind) with polling data from around the world, we have been able to explore societal attitudes towards Islam and Muslims in the West extensively. It identifies both positive and negative trends and provides a useful overview of the challenges we currently face.

While we understand the importance of structural Islamophobia, our research at HOPE not hate focuses more on anti-Muslim individuals and organisations. Our full-time monitoring of this arena gives us the ability to contribute something different to many working in the field.

Later this week we will be publishing our mini-report Bots, fake news and the anti-Muslim message on social media which explains how anti-Muslim activists are seeking to manipulate social media to amplify their prejudiced politics and reach more people.

This explores new challenges that would have been inconceivable back in 1997.

Next month, we will be producing another report profiling hundreds of Islamophobic people and organisations from across the globe.

Split into thematic sections including anti-Muslim street movements, the ideas engine, international counter-jihad groups, and mainstream enablers, this report – running to over 75,000 words – will be the most comprehensive of its kind yet produced.

Of course, in addition to our research understanding the threat, we have spent years fighting back by undermining the purveyors of Islamophobia and working in communities to make them more resilient to the hateful messages of groups like the English Defence League.

This is why we will also be publishing a report that explores methods of fighting back against Islamophobia, examining both our own work and that of numerous other organisations combatting the threat. We hope this will become a valuable resource for those who want to stand up and oppose hatred in their own communities.

These reports will all be available online and then eventually as a downloadable PDF. We hope that together they will contribute to our understanding of Islamophobia and help in the continuing struggle to combat it.