HOPE not hate uses cookies to collect information and give you a more personalised experience on our site. You can find more information in our privacy policy. To agree to this, please click accept.

A far-right party founded by nazis is taking its seat at the table of government in Sweden.

While the Sweden Democrats (SD) will be given no cabinet seats and thus not formally join the country’s new ruling coalition, its new position (after Sweden’s September elections) as the single biggest party on the right has given it far-reaching influence.

As of 18 October, the SD has been declared a “collaborative partner” of PM Ulf Kristersson’s incoming, right-leaning government – an extraordinary agreement which will see the SD set up a special “coordination secretariat” within the Government offices and convene with the coalition’s formal members, the Moderates, the Christian Democrats and the Liberals, in an “external cabinet” (collectively, the four parties are referred to by their detractors as the “blue-browns”).

The SD’s greatest triumph, however, is to have negotiated a policy agenda for the new government that includes virtually everything it wanted, and very little that it did not.

The agenda includes proposals to drastically reduce the ability of foreigners to become citizens, or for them to seek work, to immigrate to or seek asylum in Sweden, as well as encourage “voluntary repatriation” of immigrants, make all residency permits temporary, withhold welfare services from non-citizens, and deport residents who are found to be “disrespectful of Swedish values” or “lacking in morals” – the list goes on.

Much of the policy agenda (known as the “Tidö Agreement”, after Castle Tidö where the agenda was negotiated by the four parties) is aimed at making life harder for non-citizens and to deter new people from coming to the country. In fact, SD leader Jimmie Åkesson boasts that Sweden is about to undergo a “paradigm shift” in terms of its migration policies.

The remainder of the agenda touches on issues around law and order, where the new government is committed to introduce a slew of repressive and authoritarian measures, ostensibly in order to empower police and the courts to curb organised crime.

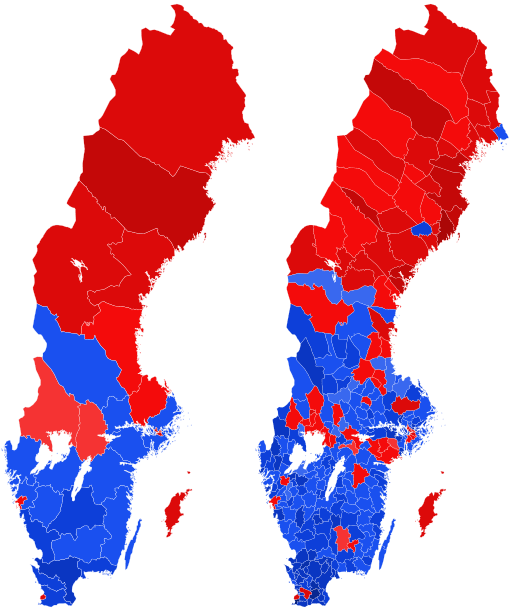

The alliance between the SD and the centre right has split Swedish politics down the middle.

The neoliberal Centre Party has abandoned its long-standing place in the right-leaning bloc and refuses to have anything to do with the SD. Even one of the parties of the new government itself, the Liberals, is uneasy; the party is undergoing a minor civil war over the leadership’s decision to get into bed with the far right, and their political group in the European Parliament is threatening to expel them.

The Swedish public is as strongly polarised as the Parliament, while civil society and watchdog groups are alarmed, and some minorities fear for their safety.

The Sweden Democrats party was founded in 1988. The men who founded it were veterans of Swedish neo-nazi and neo-fascist movements, and their vision for the new party was clear – the SD was to become the political vehicle for racist nationalism. It was to take their movement into power.

Other far-right parties and groups came and went, but the Sweden Democrats dug in for the long haul. With a mixture of populism and ethnonationalism, consistently blaming all social ills on immigrants and refugees, the party managed to tap into the racist, nationalist and authoritarian sentiments that mainstream parties disavowed but which had always simmered beneath the surface of some Swedish communities.

With each election the SD picked up more and more local council seats – particularly in the southern Skåne region, which has long been the party’s political heartland, and from where most of the current leadership hails.

The current party leader, Jimmie Åkesson, joined the party in 1994 at a time when militant skinheads were still the most visible component of the SD. As recently as 1999, the Swedish Security Service was still openly monitoring the party as a part of the right-wing extremist milieu and a threat to the “internal security of the realm”.

In 2005, Åkesson became party chairman, and in 2010 he took the SD into parliament for the first time, with some 5% of the vote. Back then, the Swedish public and the political class were universal in their detestation of the SD. Any dealings with them by the other parties were unthinkable.

Fifteen years later, it is a different story. While polls show the SD remains the single most widely disliked political phenomenon in Sweden among the general public, the party has grown its base and picked up disaffected voters from the Social Democrats and the centre right, increasing its vote share to a fifth of the electorate.

The true key to its breakthrough, however, was finally gaining the acceptance and allyship of the right-leaning parties.

As recently as the last election in 2018, the firewall against collaborating with SD from all the mainstream parties remained intact. But when the centre-right bloc fell apart in 2019 (partly over how to deal with the SD), Swedish politics entered uncharted waters.

In 2021, three out of the four right-leaning parties – the Moderates, the Christian Democrats, and the Liberals – all seemed to draw the same conclusion: without the parliamentary support of the SD, they risked being out of power indefinitely.

After eight years in opposition, centre-right voters were getting impatient for their parties to do whatever was necessary to unseat the Social Democrats – and, in any case, found themselves increasingly in agreement with the values and opinions of SD voters.

This new acceptance of the SD among these centre-right voters was due in no small part to a populist turn in Swedish media and discourse beginning years ago, especially in the wake of measures imposed in 2016 by the then-ruling Social Democrats to drastically reduce the reception of refugees from Syria and Afghanistan.

The views encapsulated by those such as the SD – in particular, the insistence that migration and crime are effectively one and the same issue – have been increasingly normalised and mainstreamed over time, across public service broadcasting as well as in the corporate centre-right press. Eventually, right-leaning pundits and politicians stopped criticising the SD altogether.

The 2022 election was closely fought, but everyone agrees that the SD emerged the clear winner, emboldened by its new position as the second biggest party in the country – even as the party’s racism, Islamophobia and ethnonationalism were repeatedly exposed by investigative journalism during the election, and in some cases openly flaunted by party representatives who courted right-wing extremist voters.

Alone of all the parties on the Swedish right, the SD grew its vote share, while the share decreased among those parties in the centre right. This has created the unprecedented situation in Swedish politics: a government dancing to the tune of an external partner, on whose support it is wholly dependent.

Nationalism has been legitimised in Sweden, and the symbolic and political significance of the Sweden Democrats moving into the Government offices of Rosenbad cannot be overstated.

However, whether the blue-brown government will be able to fully implement its far-right wishlist, and whether the special arrangement between the four parties will endure the turbulent times ahead until the next general election, remains to be seen. All we can be certain of is that a bitter winter is coming.

Read our full report into far-right extremism in Europe today.

HOPE not hate reveals two more extremist candidates from Reform UK, in the latest of a string of embarrassments for the party UPDATE: Just hours…